We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

L-O-L

Jeff Rothbard’s case made us laugh, and not in a good way.

Jeff has an unfortunate knack for fraud. He’s not likely to change his ways, given that he’s “an older man with serious health problems.”

His district court sentenced him to 24 months, even though the Presentence Report suggested a home confinement and halfway house, due to Jeff’s particularly virulent form of leukemia. Jeff has stayed alive this long because he takes nilotinib, a one-of-a-kind drug that holds the cancer in check. He needs the drug every day: if the nilotinib is discontinued even for briefly, the leukemia will come roaring back.

His district court sentenced him to 24 months, even though the Presentence Report suggested a home confinement and halfway house, due to Jeff’s particularly virulent form of leukemia. Jeff has stayed alive this long because he takes nilotinib, a one-of-a-kind drug that holds the cancer in check. He needs the drug every day: if the nilotinib is discontinued even for briefly, the leukemia will come roaring back.

There’s a catch. The drug costs about $125,000 a year.

On appeal, Jeff complained that incarceration could well kill him, because the BOP was unlikely to give him such an expensive drug. The BOP maintains a “formulary” (a listing) of drugs that its physicians are permitted to prescribe. Nilotinib is not on the list.

But the BOP told the district court that if one of its doctors believes that a patient needs a non-formulary drug, the doctor may prescribe it by following certain procedures. The BOP said a new inmate could continue on non-formulary drugs for four days after arrival, during which time he would be assessed. The BOP assured the court it could approve non-formulary drugs in a matter of hours, if need be. In fact, the BOP said it had received 10 requests by its doctors for nilotinib in the last six years, and all had been approved.

Last week, the 7th Circuit upheld the sentence, concluding it was reasonable. While the Circuit admitted that the BOP had “an incentive to be sparing with its orders for particularly expensive non-formulary drugs, such as nilotinib, there is no evidence… that it has done so… The record shows that BOP has ordered nilotinib itself on ten other occasions, evidently in recognition of the fact that it might be essential (as it apparently is for Rothbard).”

Of course, what the Circuit overlooked was that nilotinib was approved the ten times a BOP doctor actually requested it. That stat overlooks how many time a prisoner needed the drug but the doctor at the institution refused to make the request to the Central Office.

In this case, the 7th admitted the decision was a close one because the “BOP is not willing or able to pre-commit to nilotinib for Rothbard, before he has gone through the intake examination at the prison medical center. Although it might be sensible in cases such as this one for BOP to have some way of examining people before they report, that is not its practice and we are not persuaded that the lack of a pre-report examination is independently actionable. In addition, we cannot find fault with BOP’s reservation of the right to conduct its own medical examination.”

In this case, the 7th admitted the decision was a close one because the “BOP is not willing or able to pre-commit to nilotinib for Rothbard, before he has gone through the intake examination at the prison medical center. Although it might be sensible in cases such as this one for BOP to have some way of examining people before they report, that is not its practice and we are not persuaded that the lack of a pre-report examination is independently actionable. In addition, we cannot find fault with BOP’s reservation of the right to conduct its own medical examination.”

What made us laugh was the Court’s warning to the BOP. It said that if Jeff “shows up at a BOP facility and discovers that the responsible people are dragging their feet in a way that deprives him for any significant time of his nilotinib, or if the BOP evaluator (contrary to all of the evidence we have seen) takes the position that a medically suitable alternative from the formulary exists, Rothbard is free to use the BOP’s grievance procedures to complain about any such problem.”

Now there’s a threat to make the BOP director quake in his boots. If Jeff is denied the drug he cannot live without, he can file his BP-8. BP-9, BP-10 and BP-11. Then after the 230+ days it takes to complete the largely futile BOP grievance procedures, if Jeff has still not gotten the drug, he can file a habeas corpus action (provided he’s still alive).

In a sharp dissent, Judge Richard Posner showed no confidence in the BOP: “Essentially the prosecution, the district court, and now my colleagues, ask that the Bureau of Prisons be trusted to give the defendant, in a federal prison, the medical treatment that he needs for his ailments. Yet it is apparent from the extensive literature on the medical staff and procedures of the Bureau of Prisons (a literature ignored by my colleagues) that the Bureau cannot be trusted to provide adequate care to the defendant.”

In a sharp dissent, Judge Richard Posner showed no confidence in the BOP: “Essentially the prosecution, the district court, and now my colleagues, ask that the Bureau of Prisons be trusted to give the defendant, in a federal prison, the medical treatment that he needs for his ailments. Yet it is apparent from the extensive literature on the medical staff and procedures of the Bureau of Prisons (a literature ignored by my colleagues) that the Bureau cannot be trusted to provide adequate care to the defendant.”

This decision ought to read by anyone who has a medical issue with the BOP.

United States v. Rothbard, Case No. 16-3996 (7th Cir., March 17, 2017)

THE LESS SAID, THE BETTER

Ryrica Custis, a Virginia prisoner, had lost his toes in a pre-prison accident. The prison assigned him to an upper bunk anyway, and of course he fell off the ladder trying to climb in. He filed an inmate complaint in the grievance system, but the prison grievance manual listed the wrong address to which to send it. By the time Ry remailed it to the right place, the prison said he was too late.

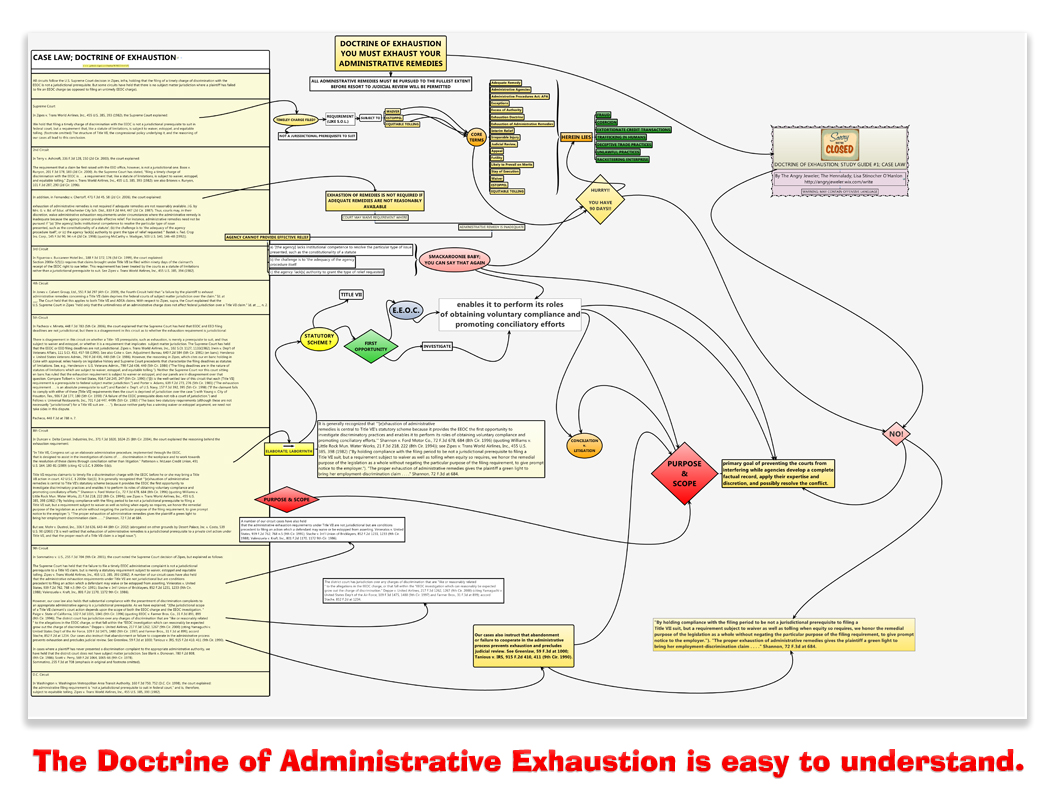

Ry sued in federal court for injuries he had suffered. Under the Prison Litigation Reform Act, inmates may file federal suits about prison conditions only if they first exhaust administrative remedies in the prison grievance system. In Jones v. Bock, a 2007 case, the Supreme Court held that failure to exhaust remedies is no more than an affirmative defense. In other words, if the prison fails to raise it in its answer, the failure to exhaust is waived and the suit may proceed.

After Jones, the 4th Circuit held in Moore v. Bennette that if the inmate did not plead in the complaint that he had exhausted remedies, the court could dismiss it “so long as the inmate is first given an opportunity to address the issue.” Some district courts, like the one Ry had sued in, started acting on their own to dismiss inmate suits where the courts deemed that the inmate had not exhausted remedies.

After Jones, the 4th Circuit held in Moore v. Bennette that if the inmate did not plead in the complaint that he had exhausted remedies, the court could dismiss it “so long as the inmate is first given an opportunity to address the issue.” Some district courts, like the one Ry had sued in, started acting on their own to dismiss inmate suits where the courts deemed that the inmate had not exhausted remedies.

Last week, the 4th Circuit put a stop to that practice. It explained that in Moore, the district court did not raise exhaustion sua sponte (on its own motion). Instead, the prison administration raised it as an affirmative defense. The Circuit held that Jones means that (1) an inmate does not have to say anything about exhaustion in his complaint, and (2) unless the inmate actually admits in his complaint that he did not exhaust remedies, district courts may not dismiss the case on its own. To the extent that 4th Circuit decisions have said otherwise, they were overruled.

Custis v. Davis, Case No. 15-7533 (4th Cir., Mar. 23, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root