We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

HUH?

Ryan Gibbs was just one of those perennial bad boys, with a record as long as your arm and a demonstrated lack of interest in conforming his conduct to the strictures of the law. In front of a district court for possession with Ryan faced a Guidelines-suggested 151-188 month sentencing range. The government asked for 216 months. The most Ryan could have gotten was a 240-month term.

Ryan Gibbs was just one of those perennial bad boys, with a record as long as your arm and a demonstrated lack of interest in conforming his conduct to the strictures of the law. In front of a district court for possession with Ryan faced a Guidelines-suggested 151-188 month sentencing range. The government asked for 216 months. The most Ryan could have gotten was a 240-month term.

The district judge, rambling “none too clearly” (as the Court of Appeals lamented), decided that Ryan was incorrigible:

When I look at the 3553(a) factors apart from the “nature and circumstances of the offense,” your “history and characteristics” of you as a defendant does [sic] not indicate that there should be any leniency at all; that they [anteced‐ent unclear] “reflect the seriousness of the offense,” “promote respect for the law,” which your history and characteristics indicate that you have no respect for the law; “provide just punishment.” Nothing — No previous sentence that this Court has imposed or other Courts have deterred you from your criminal conduct.

With this gibberish constituting the sum and substance of the district court’s application of the sentencing factors of 18 USC 3553(a), the judge slapped Ryan with 216 months.

Last week, the 7th Circuit affirmed the sentence. No surprise there – the government wins over 92% of the time in criminal appeals to begin with.

But the Court of Appeals upheld the decision primarily because it sensed it could trust the judge’s (and, to a lesser extent, the prosecutor’s) gut.

The Circuit admitted that no one in the case “attempted a sophisticated analysis of the likely consequences… of adding roughly two years to the sentence he would have been given had the judge stopped at the top of the guideline range… both the prosecution and the judge based the 216-month sentence (proposed by the government, imposed by the judge) on a hunch. As the prosecutors as well as the judge are highly experienced, their hunches are likely often to be reliable.”

The Circuit admitted that no one in the case “attempted a sophisticated analysis of the likely consequences… of adding roughly two years to the sentence he would have been given had the judge stopped at the top of the guideline range… both the prosecution and the judge based the 216-month sentence (proposed by the government, imposed by the judge) on a hunch. As the prosecutors as well as the judge are highly experienced, their hunches are likely often to be reliable.”

The Court said that, after all, the government can suggest any sentence within the statutory range and the judge can impose any sentence within the statutory range. Plus, the panel argued, the “briefs and argument of defense counsel in this case bordered on the perfunctory.”

So the judge and the AUSA are “highly experienced” and their hunches are “reliable.” Defense counsel, on the other hand, is a legal klutz filing cookie-cutter motions and soulless briefs. It sounds as though imposition of a sentence after proper consideration of the Guidelines and sentencing factors in Sec. 3553(a) is a privilege reserved only for defendants who have good lawyers or face lousy prosecutors and a neophyte judge.

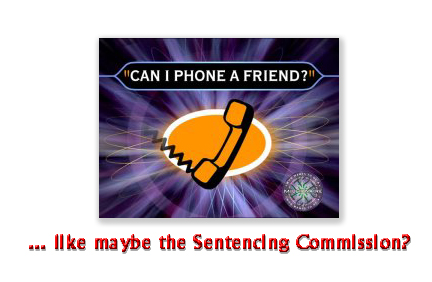

Judge Richard Posner, the author of the decision and an appellate jurist for whom we have great respect, said that “some consideration, however, should be given to the possibility of basing a prison sentence – at least a very long one (and an 18-year sentence is very long) – on something other than a hunch.” We agree wholeheartedly. But he then proceeded on a flight of impractical fancy by suggested that maybe the sentencing judge should have called the Sentencing Commission, which then would given the AUSA, court and defense counsel guidance on why it set the Guidelines where it did, and might even propose the right out-of-guidelines sentence in this particular case. The parties might find the Sentencing Commission “a valuable resource,” Judge Posner opined.

What a capital idea! For that matter, the district courts might just want to call Congress for guidance on why the statutory penalties are as they are, or ring up the President for his view as to whether it should peremptorily commute the sentence, or even ask the defendant’s mother what punishment she found to be the most effective when Ryan was a mere lad. To be sure, the Sentencing Commission could not be so busy that it wouldn’t be willing to give a few minutes of time to arbitrate an individual sentence in Ryan’s case (or in any of the other 80,000 criminal sentences that occur in federal courts annually).

What a capital idea! For that matter, the district courts might just want to call Congress for guidance on why the statutory penalties are as they are, or ring up the President for his view as to whether it should peremptorily commute the sentence, or even ask the defendant’s mother what punishment she found to be the most effective when Ryan was a mere lad. To be sure, the Sentencing Commission could not be so busy that it wouldn’t be willing to give a few minutes of time to arbitrate an individual sentence in Ryan’s case (or in any of the other 80,000 criminal sentences that occur in federal courts annually).

In the days before the Guidelines, judges sentenced anywhere within the statutory range virtually without oversight or discretion. The Guidelines were to change all of that. In Gibbs, the 7th Circuit has handed down a decision that enshrines a judge’s “hunch” as a standard that trumps all others. What’s nearly as bad, the Court has suggested that maybe district courts should start using the U.S. Sentencing Commission as a “phone-a-friend” in troublesome sentencing cases, a development undoubtedly as unwelcome to the Commission is it would be for people like us who believe that judging is for judges.

In the days before the Guidelines, judges sentenced anywhere within the statutory range virtually without oversight or discretion. The Guidelines were to change all of that. In Gibbs, the 7th Circuit has handed down a decision that enshrines a judge’s “hunch” as a standard that trumps all others. What’s nearly as bad, the Court has suggested that maybe district courts should start using the U.S. Sentencing Commission as a “phone-a-friend” in troublesome sentencing cases, a development undoubtedly as unwelcome to the Commission is it would be for people like us who believe that judging is for judges.

United States v. Gibbs, Case No. 16-1747 (7th Cir., Jan. 6, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root