We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

A “TWO-FER”

It’s rare for an appellate court to hand down a vindictive sentencing decision. It’s rarer still for an appellate court to use its 28 USC § 2106 power to dictate a remedy, instead of just remanding the case to a district court. The 5th Circuit handed down a decision last week containing both, a genuine “two-fer.”

It’s rare for an appellate court to hand down a vindictive sentencing decision. It’s rarer still for an appellate court to use its 28 USC § 2106 power to dictate a remedy, instead of just remanding the case to a district court. The 5th Circuit handed down a decision last week containing both, a genuine “two-fer.”

And the next blue moon is still a few months away. Imagine.

What’s vindictive sentencing? It’s pretty easy to understand. A district court sentences you to 121 months, which happens to be the low end of your Guidelines range. But the Judge incorrectly gave you one point too many, so your Guideline range was really 108-135 months. You appeal, and the Circuit Court corrects the judge’s error and remands the case for resentencing. When you get to resentencing the district judge – unhappy at being publicly corrected by the appellate court – takes it out on you. You get resentenced to 135 months, the top of your new Guidelines range (and 14 months more than if you had just kept your appellate lawyer’s mouth shut).

That, my friend, is vindictive sentencing: very effective in discouraging defendants from appealing, but brutal on due process rights.

That, my friend, is vindictive sentencing: very effective in discouraging defendants from appealing, but brutal on due process rights.

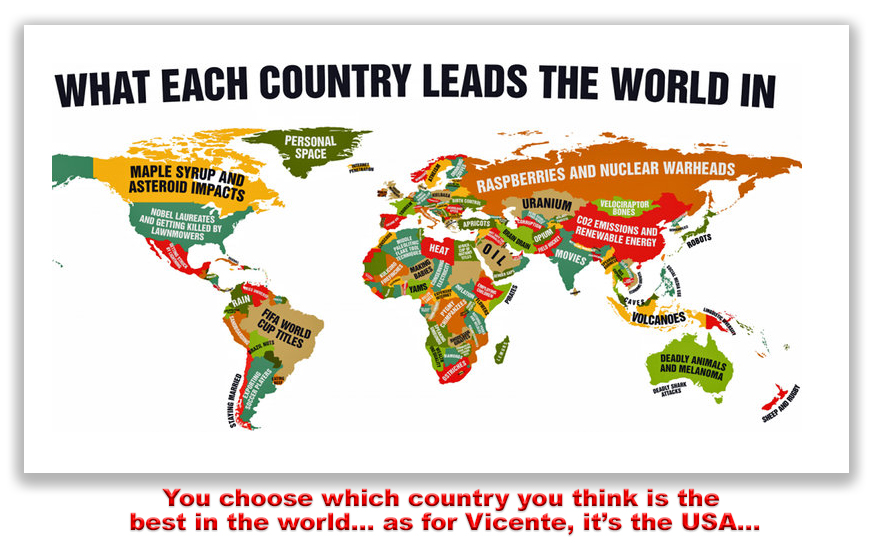

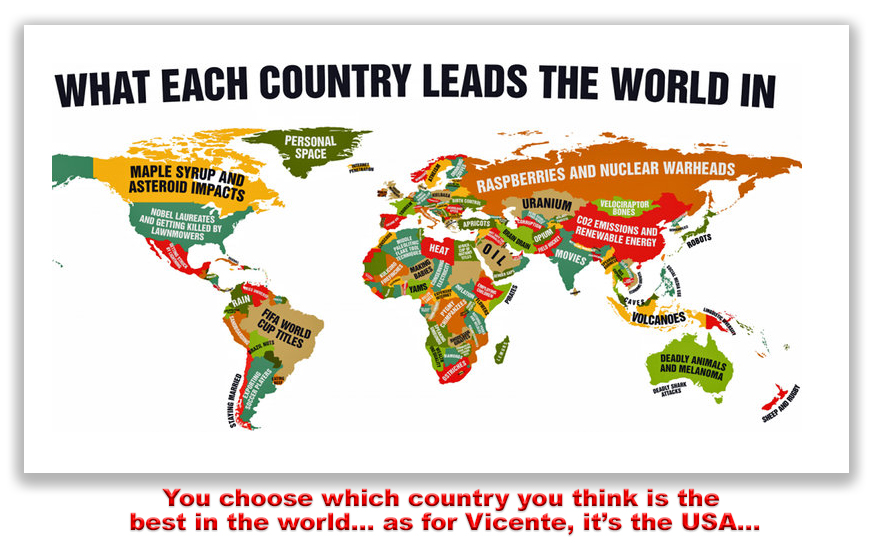

That brings us to Vicente Galileo Penado-Aparicio, a guy who loves America. In fact, he loves America so much that he keeps sneaking into the USA from Mexico, even after being arrested and imprisoned for sneaking into America on prior occasions. After he got caught the latest time – while his supervised release term was still running on his prior sentence for an illegal border crossing – the district court sentenced him to 72 months, with a separate 24-month term for violating supervised release. It still only totaled 72 months, because the district court said the supervised release should run concurrently, that is, at the same time as the 72-month sentence.

Unfortunately, Vince’s guideline sentencing range was calculated using the 2016 version of the Guidelines, which were harsher on America-lovin’ aliens like Vince than were the Guidelines in effect when he climbed the impenetrable wall. That, you recall from high school government class, is a violation of the Constitution’s Ex Post Facto Clause. Simply put, you cannot use a law passed after the fact to make some conduct criminal if it wasn’t criminal at the time, or to make a punishment for a crime harsher than it was when the crime was committed.

Unfortunately, Vince’s guideline sentencing range was calculated using the 2016 version of the Guidelines, which were harsher on America-lovin’ aliens like Vince than were the Guidelines in effect when he climbed the impenetrable wall. That, you recall from high school government class, is a violation of the Constitution’s Ex Post Facto Clause. Simply put, you cannot use a law passed after the fact to make some conduct criminal if it wasn’t criminal at the time, or to make a punishment for a crime harsher than it was when the crime was committed.

Vince’s appellate lawyer argued the ex post facto violation to the 5th Circuit, and it agreed, vacating Vince’s sentence and sending it back to the trial court for resentencing.

At resentencing, the district court expressed its unhappiness that no one called the ex post facto problem to its attention at the first sentencing. That, of course, was the fault of the lawyers (both Vince’s and the government’s). But the court could hardly throw them in jail (as much as that might seem to some to be a good idea). So the judge looked around the courtroom for someone on which to take out its frustrations. Lo and behold, there was Vince!

The judge resentenced Vince to 60 months (instead of 72 months) and reimposed the 24-month supervised release sentence. With one change – the court said while the supervised release sentence “would have been concurrent at the sentence I gave before… it’s not going to be concurrent now.” Vince was thus sentenced to a consecutive 24-month supervised sentence, for a total of 84 months (a year longer than the original sentence.)

The judge resentenced Vince to 60 months (instead of 72 months) and reimposed the 24-month supervised release sentence. With one change – the court said while the supervised release sentence “would have been concurrent at the sentence I gave before… it’s not going to be concurrent now.” Vince was thus sentenced to a consecutive 24-month supervised sentence, for a total of 84 months (a year longer than the original sentence.)

Last week, the 5th Circuit reversed the sentence again. Whenever a district court resentences a defendant to a longer imprisonment after a remand from a court of appeals, the new sentence is presumed by law to be vindictive, and thus violates a defendant’s due process rights under the 5th Amendment. The presumption may be rebutted if the sentencing court “articulates specific reasons, grounded in particularized facts that arise either from newly discovered evidence or from events that occur after the original sentencing” that warrant a more severe sentence.

For example, at sentencing, both lawyers and the Probation Officer added up the Guidelines points wrong, scoring the defendant at a Total Offense Level of 22 instead of 24. The sentence was reversed for a completely different reason. On resentencing, the court caught the error, and the defendant was resentenced at the correct but higher range. There, the presumption of vindictiveness was rebutted: no one was trying to flay the defendant for having had the temerity to appeal.

For example, at sentencing, both lawyers and the Probation Officer added up the Guidelines points wrong, scoring the defendant at a Total Offense Level of 22 instead of 24. The sentence was reversed for a completely different reason. On resentencing, the court caught the error, and the defendant was resentenced at the correct but higher range. There, the presumption of vindictiveness was rebutted: no one was trying to flay the defendant for having had the temerity to appeal.

Vince’s district court said it was relying on Vince’s “extensive” criminal record in imposing the higher sentence, but the 5th Circuit didn’t buy that. The appeals court noted that there was nothing new about that criminal record: the district court had the same information in front of it when Vince first got sentenced. Nothing undercut the presumption that the district court vindictively re-sentenced Vince, the 5th said, and for that reason, the 84 months had to be set aside.

A court of appeals has the authority under 28 USC § 2106 to “modify, vacate, set aside or reverse any judgment.” This is one powerful little section of the law. It essentially means the court of appeals is free to fashion its own remedy – here, its own sentence – if it wants to. With great power comes great responsibility, and for that reason, courts of appeal apply 28 USC § 2106 very sparingly.

But the Circuit believed it was called for here. “Granting appellate relief to defendant only requires that we exercise our appellate authority to modify the consecutive sentencing designation so that his sentence runs concurrent with his revocation sentence… More importantly, granting his request will effectively eliminate any perception of a potential constitutional error.” The 5th thus modified Vince’s sentence so that the 24-month supervised release violation sentence again ran concurrent with his underlying month sentence.

But the Circuit believed it was called for here. “Granting appellate relief to defendant only requires that we exercise our appellate authority to modify the consecutive sentencing designation so that his sentence runs concurrent with his revocation sentence… More importantly, granting his request will effectively eliminate any perception of a potential constitutional error.” The 5th thus modified Vince’s sentence so that the 24-month supervised release violation sentence again ran concurrent with his underlying month sentence.

So, after all the dust settled from two sentencing and two trips to New Orleans, Vince got a net sentence of 60 months.

United States v. Penado-Aparicio, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 25673 (Aug 13, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

Many see supervised release as gravy on the mashed potatoes of incarceration. While it may not be very good, it sure beats more potatoes without gravy. What courts don’t agree on is whether supervised release is intended to be for rehabilitation, extra punishment, or both.

Many see supervised release as gravy on the mashed potatoes of incarceration. While it may not be very good, it sure beats more potatoes without gravy. What courts don’t agree on is whether supervised release is intended to be for rehabilitation, extra punishment, or both. Comparing prison time to supervised release time, the Circuit said, “likens clementines to kumquats and likely draws on subjective choice.” Still, because the district court reduced [the] term of incarceration by only three months and increased his term of supervised release by six years, the “second sentence was indeed harsher than the first. Because the prisoner’s second sentence was harsher than his first and he was sentenced ‘by the same judge, in the same posture, following a successful appeal… a presumption of vindictiveness applies to any unexplained increase in his sentence.”

Comparing prison time to supervised release time, the Circuit said, “likens clementines to kumquats and likely draws on subjective choice.” Still, because the district court reduced [the] term of incarceration by only three months and increased his term of supervised release by six years, the “second sentence was indeed harsher than the first. Because the prisoner’s second sentence was harsher than his first and he was sentenced ‘by the same judge, in the same posture, following a successful appeal… a presumption of vindictiveness applies to any unexplained increase in his sentence.” Because the district court considered the same factors – alcohol abuse and medical condition – in the second sentencing as it did in the first, the 4th “conclude[d] that Pearce’s presumption of vindictiveness arose and was not rebutted… In these circumstances, we vacate the sentence and remand for resentencing.

Because the district court considered the same factors – alcohol abuse and medical condition – in the second sentencing as it did in the first, the 4th “conclude[d] that Pearce’s presumption of vindictiveness arose and was not rebutted… In these circumstances, we vacate the sentence and remand for resentencing.