We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

YOU’VE GOT TO BE A PLAYER

The Freedom of Information Act is a pretty slick statute. Using FOIA, Joe Average Citizen can obtain all sorts of information from government agencies, quite often including information the government would rather Joe not have.

Journalists used FOIA to get the FBI file on Dr. Martin Luther King. Hillary’s emails were released because of FOIA requests. The IRS targeting scandal erupted because of an FOIA request. And on a more individualized scale, a casual Freedom of Information Act request we made back in 1994 for an inmate with a life sentence resulted in his release 12 years later.

Journalists used FOIA to get the FBI file on Dr. Martin Luther King. Hillary’s emails were released because of FOIA requests. The IRS targeting scandal erupted because of an FOIA request. And on a more individualized scale, a casual Freedom of Information Act request we made back in 1994 for an inmate with a life sentence resulted in his release 12 years later.

As an old law partner we once practiced with liked to say, you never know what’s under a rock until you turn it over. Picture the FOIA as the spud bar you use to turn over those rocks.

All is not roses, by any means. First, FOIA applies only to federal agencies, and then only to executive branch agencies. FOI the FBI? Sure thing. CIA? Why not? But you cannot use the FOIA to U.S. Probation Office documents (it’s a judicial branch agency) or to get into the Government Accountability Office files (the GAO is a legislative branch agency).

The FOIA has some very restrictive deadlines for agencies to respond, which should ensure that requesters get their documents quickly. Anyone who’s ever filed an FOIA request knows that the agencies honor those deadlines in the breach. And why not? A requester’s only recourse is to sue, after which the agencies will drag their bureaucratic feet even more, and then finally send a few documents and tell the court that they have no idea what the requester’s beef is – he or she got the documents.

The FOIA has some very restrictive deadlines for agencies to respond, which should ensure that requesters get their documents quickly. Anyone who’s ever filed an FOIA request knows that the agencies honor those deadlines in the breach. And why not? A requester’s only recourse is to sue, after which the agencies will drag their bureaucratic feet even more, and then finally send a few documents and tell the court that they have no idea what the requester’s beef is – he or she got the documents.

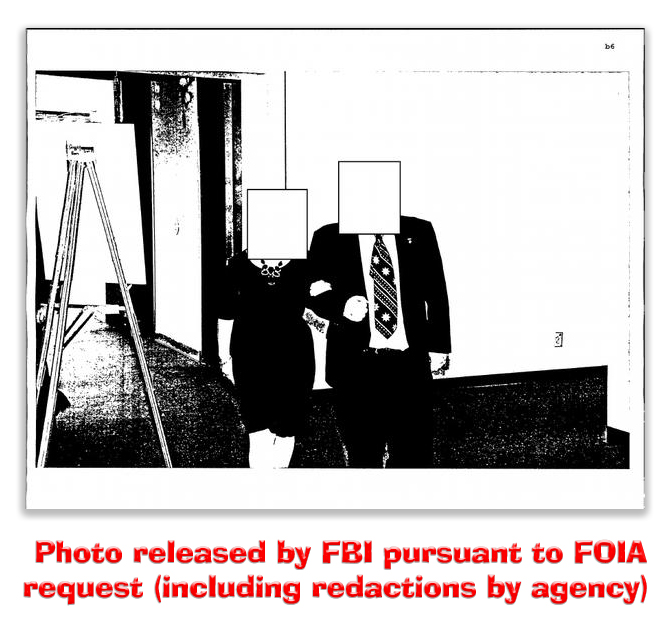

And the document response will be incomplete, and documents that are turned over will have words, sentences, paragraphs – sometimes the whole page – blacked out (“redacted” is the term the agencies use) because of one or another exemption from disclosure. That requires more litigation and more piecemeal response. We worked on one plain vanilla FOIA request filed with a U.S. Attorney’s office and the FBI in 2009 that was finally fulfilled after seven years of litigation. Sadly, the Obama Administration – which promised to be the most “transparent” in history – was one of the least compliant with the FOIA.

Still, like the state lotteries tell us, you have to play to win. That’s why we were so bemused by a D.C. Court of Appeals decision this past week in an FOIA action brought by well-known post-conviction lawyer Jeremy Gordon and his non-profit arm, Prisology.

Prisology sued the Federal Bureau of Prisons under the FOIA, charging that the BOP violated the statute because it did not publish inmate grievances and its responses, Federal Tort Claims Act lawsuit settlement information, and reports on compassionate releases it has recommended to courts. Prisology argued that a section of the FOIA requiring publication of agency final opinions, policy statements not published in the Federal Register, and administrative staff manuals, mandated that the BOP post up the omitted information on the Internet.

Prisology sued the Federal Bureau of Prisons under the FOIA, charging that the BOP violated the statute because it did not publish inmate grievances and its responses, Federal Tort Claims Act lawsuit settlement information, and reports on compassionate releases it has recommended to courts. Prisology argued that a section of the FOIA requiring publication of agency final opinions, policy statements not published in the Federal Register, and administrative staff manuals, mandated that the BOP post up the omitted information on the Internet.

But you’ve gotta be a player first, and Prisology overlooked that. It seems the nonprofit never requested bothered to request any information under the FOIA – so it could be turned down – before filing its two-page lawsuit.

Earlier this week, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals reminded Prisology that it’s pretty basic first-year law school dogma that anyone bringing a lawsuit has to be able to allege concrete injury. Article III of the Constitution requires a “case or controversy,” and since the dawn of the Republic, that means that the party bringing the suit has to be able to allege it was injured.

The Circuit noted that “Prisology’s complaint contains no allegation of injury, general or otherwise. Even if we inferred an injury to Prisology from the Bureau’s alleged failure to publish its records electronically, this would not differentiate Prisology from the public at large… Prisology made no request of the Bureau of Prisons before bringing suit and therefore received no denial from that agency.”

The Circuit noted that “Prisology’s complaint contains no allegation of injury, general or otherwise. Even if we inferred an injury to Prisology from the Bureau’s alleged failure to publish its records electronically, this would not differentiate Prisology from the public at large… Prisology made no request of the Bureau of Prisons before bringing suit and therefore received no denial from that agency.”

Prisology argued that its lawsuit “amounted to a request for particular information,” meaning that it has standing. “The argument goes nowhere,” the Circuit replied. “To the extent that a complaint may be seen as a request, it is a request for relief from a court. If the court denies the request, the plaintiff may appeal. But a court’s refusal to grant relief cannot confer Article III standing that otherwise does not exist.”

We’re rather surprised that the plaintiff made such a rookie mistake. To nonlawyers, “standing” might seem to be a frivolous formality, and the Court acknowledged that, even while expressing its own puzzlement at Prisology’s approach:

We’re rather surprised that the plaintiff made such a rookie mistake. To nonlawyers, “standing” might seem to be a frivolous formality, and the Court acknowledged that, even while expressing its own puzzlement at Prisology’s approach:

The result here may seem overly technical. But Prisology’s predicament is one of its own making. With little effort it may have been able to satisfy the requirements of Article III. The Supreme Court over the years has taken steps to clarify the law of standing. We would not muddy the waters in order to accommodate Prisology’s recalcitrance even if we had the power to do so, which we do not.

Prisology v. Bureau of Prisons, Case No. 15-5003 (April 4, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root