We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LIKE AN EARTH GIRL, JURISDICTION IS EASY

We may as well begin 2020 with a cautionary tale. As I have previously written, arguing that federal courts lack subject-matter jurisdiction over a criminal case is a dead-bang loser. Yet, there is a small but persistent cohort of inmates – many of whom inhabit the prison law library – who espouse whack-a-doodle ideas about the law and, for a fee payable in items from the institution commissary – are way too willing to share them with fellow prisoners.

We may as well begin 2020 with a cautionary tale. As I have previously written, arguing that federal courts lack subject-matter jurisdiction over a criminal case is a dead-bang loser. Yet, there is a small but persistent cohort of inmates – many of whom inhabit the prison law library – who espouse whack-a-doodle ideas about the law and, for a fee payable in items from the institution commissary – are way too willing to share them with fellow prisoners.

The 2nd Circuit underscored that last week in an opinion that expressed both patience and exasperation with a pro se whack-a-doodle appellate filing by a federal inmate.

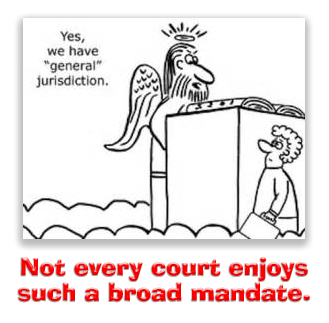

First, a word about jurisdiction. Federal courts (except for the Supreme Court) were created by statutes passed by Congress. They are what are known as courts of limited jurisdiction. That is to say that a federal court only has the power to decide an issue that Congress has authorized it to decide. This is what is known as subject-matter jurisdiction. Your neighbor’s kid broke your window with a baseball? Try suing in federal court, and see what happens. Your case will be tossed.

Proceeding hand in hand with subject-matter jurisdiction is personal jurisdiction. A federal court has to have authority over the person of the defendant. If a diminutive elderly woman rams your new Bentley at the Rose Bowl, you cannot return home to Frog Level, North Carolina, and sue her in the Federal District Court for the Western District of North Carolina. There may be subject-matter jurisdiction (diversity of citizenship and sufficient damages to the Bentley, which we won’t get into), but the Little Old Lady from Pasadena has no contacts with the Western District of North Carolina. There’s no personal jurisdiction.

Proceeding hand in hand with subject-matter jurisdiction is personal jurisdiction. A federal court has to have authority over the person of the defendant. If a diminutive elderly woman rams your new Bentley at the Rose Bowl, you cannot return home to Frog Level, North Carolina, and sue her in the Federal District Court for the Western District of North Carolina. There may be subject-matter jurisdiction (diversity of citizenship and sufficient damages to the Bentley, which we won’t get into), but the Little Old Lady from Pasadena has no contacts with the Western District of North Carolina. There’s no personal jurisdiction.

In the federal criminal law sphere, subject-matter jurisdiction – as I have said before – is easy. If the grand jury has indicted you for violating a federal criminal statute, a federal district court has subject-matter jurisdiction. But, as defendant Raymond McLaughlin asked the Second Circuit, how about personal jurisdiction?

Ray’s house was in foreclosure. Rather than looking in the mirror to find someone to blame (if you don’t make your house payment, the bank forecloses and takes your house back), Ray decided it was all the state court judge’s fault. He filed documents with the IRS showing he had paid the state court judge $300,000. Of course, he had not. If he had had that kind of money, he would have made his house payments. But Ray claimed he had greased the judge’s palm, intending to get the IRS to go after the judge for failing to report income and thus to make His Honor’s life a living hell.

The scheme fell apart, and Ray was convicted of making a false statement to a government agency in violation of 18 USC § 1001.

Before his conviction, Ray filed a truckload of pro se motions arguing, among other things, that the district court lacked personal jurisdiction over him. Ray had bought into the “sovereign citizen” movement, which in essence believes the federal government is illegitimate and therefore that its laws are not binding. As Ray’s District Court judge observed, the “sovereign citizens” seek to “clog the wheels of justice” by raising frivolous arguments that the courts and the Constitution lack authority.

Before his conviction, Ray filed a truckload of pro se motions arguing, among other things, that the district court lacked personal jurisdiction over him. Ray had bought into the “sovereign citizen” movement, which in essence believes the federal government is illegitimate and therefore that its laws are not binding. As Ray’s District Court judge observed, the “sovereign citizens” seek to “clog the wheels of justice” by raising frivolous arguments that the courts and the Constitution lack authority.

“Sovereign citizens” can, however, make a claim that hardly anyone else can. Their claims have a perfect record in federal court: none has ever won.

Neither did Ray. The 2nd Circuit explained that whenever a district court has subject-matter jurisdiction over the criminal offenses charged, it has personal jurisdiction over the defendants charged in the indictment and present before the court to answer those charges. A federal district has subject-matter jurisdiction over any indictment charging that a federal law has been broken. Therefore, it has personal jurisdiction over the defendant, no matter whether he or she walks in voluntarily or is dragged in by federal agents.

As the Circuit put it, a defendant need not “actually participate in the proceedings in order for the court to have personal jurisdiction over the defendant.”

It is pretty simple, the 2nd said. The indictment charged Ray, and Ray was present before the district court. “Accordingly, the District Court had personal jurisdiction over McLaughlin and the judgment is valid.”

It is pretty simple, the 2nd said. The indictment charged Ray, and Ray was present before the district court. “Accordingly, the District Court had personal jurisdiction over McLaughlin and the judgment is valid.”

Note: personal jurisdiction should not be confused with venue. The Sixth Amendment gives a defendant “the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed.” In other words, Ray could not have been put on trial in the District of Hawaii – no matter how much nicer the weather – for a crime that allegedly occurred in Connecticut. But “venue” is a topic for another day.

United States v. McLaughlin, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 38626 (2nd Cir. Dec. 30, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root