We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SIX MINUTES OF BAD ADVICE COST DEFENDANT AN EXTRA 14 YEARS

Jonathan Kearn was indicted on three counts alleging he possessed some unsavory and illegal photos of his own children. He was looking at a 30-year sentence when the government threw him a lifeline: it offered him a Rule 11(c)(1)(C) plea deal with a fixed 10-year sentence in exchange for a guilty plea to just one of the three counts.

Jonathan Kearn was indicted on three counts alleging he possessed some unsavory and illegal photos of his own children. He was looking at a 30-year sentence when the government threw him a lifeline: it offered him a Rule 11(c)(1)(C) plea deal with a fixed 10-year sentence in exchange for a guilty plea to just one of the three counts.

Most plea agreements specify that, while the government and defendant may anticipate the Sentencing Guidelines will recommend a sentence within a certain range, the court is not bound by their anticipations and may impose whatever sentence it believes is appropriate. Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1)(C), however, lets the government and criminal defendants lock the court into a binary choice: the judge may either accept the plea deal, which comes with an agreement that the defendant will get a certain sentence (or occasionally, a sentence within a certain range) regardless of what the Sentencing Guidelines recommend or the judge prefers.

If the court doesn’t like the sentence specified in the 11(c)(1)(C), it can reject the deal, at which time the defendant can walk away from the agreement and go to trial. So-called (c)(1)(C) pleas are popular with defendants because they provide certainty – defendants either receive the sentence they agreed to or they can withdraw their plea.

Anyone familiar with the draconian sentences usually imposed in child pornography cases would see acceptance of the (c)(1)(C) offer made to Jon as a “no-brainer.” But not Jon’s lawyer. After exhaustively counseling his client about the (c)(1)(C) plea for all of six minutes, learned counsel convinced Jon to reject the offer and proceed to trial. You can guess the end: Jon was convicted on all three counts and sentenced to 24 years in prison.

Anyone familiar with the draconian sentences usually imposed in child pornography cases would see acceptance of the (c)(1)(C) offer made to Jon as a “no-brainer.” But not Jon’s lawyer. After exhaustively counseling his client about the (c)(1)(C) plea for all of six minutes, learned counsel convinced Jon to reject the offer and proceed to trial. You can guess the end: Jon was convicted on all three counts and sentenced to 24 years in prison.

Jon filed a 28 USC § 2255 post-conviction motion, arguing his lawyer was constitutionally ineffective during the plea-bargaining phase. The district court found that counsel didn’t tell Jon that if the court accepted the plea agreement, he would be guaranteed a 10-year sentence but if the court rejected the plea agreement, he could withdraw the plea. In fact, the district court found counsel failed to explain anything at all about Rule 11.

The district judge granted Jon’s § 2255 motion and let him plead to the 10-year offer. This week, the 10th Circuit upheld the decision.

Jon’s hang-up was that he did not want to stand in open court and “personally describe the facts of his offenses – which involved his daughters – before his family and friends in open court.” Under Rule 11, “[b]efore entering judgment on a guilty plea, the court must determine that there is a factual basis for the plea.” This requirement is intended to ensure the accuracy of the plea through some evidence that a defendant actually committed the offense.

But Jon’s lawyer told him that he had to do that in order to accept the plea. This advice, the Court said, was absolutely wrong. “The defendant does not have to provide the factual basis narrative,” the appeals court said. Instead, “[t]he district court may look to answers provided by counsel for the defense and government, the presentence report, or… whatever means is appropriate in a specific case – so long as the factual basis is put on the record.”

Jon’s lawyer didn’t know this. The lawyer admitted that he “regularly advised his clients that they would have to admit the facts surrounding the offense… and didn’t know if Mr. Kearn would actually receive a 10-year sentence if he pleaded guilty.”

Jon’s lawyer didn’t know this. The lawyer admitted that he “regularly advised his clients that they would have to admit the facts surrounding the offense… and didn’t know if Mr. Kearn would actually receive a 10-year sentence if he pleaded guilty.”

“In the plea agreement context,” the 10th ruled, “counsel has a critical obligation… to advise the client of the advantages and disadvantages of a plea agreement… Because counsel understated the benefits and overstated the burdens of the plea offer, Mr. Kearn could not make an informed choice about whether to accept it.”

The government argued that Jon could not show that his attorney’s bad advice prejudiced him because there was no evidence Jon would have taken the deal had his lawyer properly advised him. But the Court held that Jon “lacked the requisite information to weigh the options in front of him, and whatever desire he exhibited before trial is not dispositive of what he would have done if he were properly educated about the charges against him… We cannot rationally expect defendants to theorize contemporaneously about the decisions they would make if they were receiving different advice. If courts required this kind of evidence, no defendant could show prejudice.”

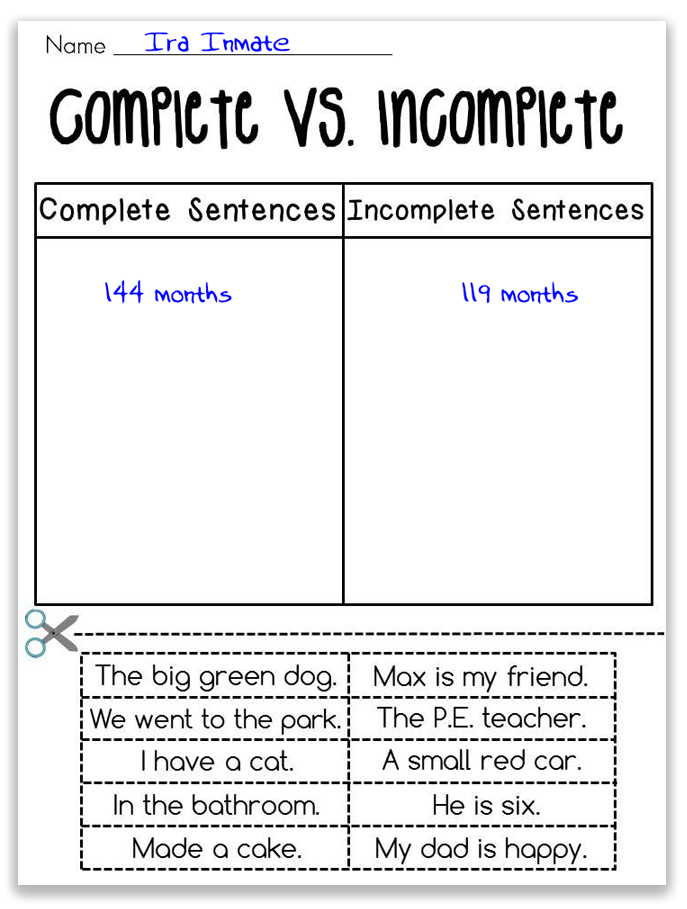

The significant disparity between the 10-year sentence Jon was offered and the 24 years he got is very relevant to the prejudice analysis, the Court said. Jon “was not adequately informed that the district court would have been bound by the agreed-upon sentence. Thus, counsel improperly skewed his attention away from the sizeable sentencing disparity he faced in favor of the need for him to personally supply a factual basis… Sentencing disparity is strong evidence of a reasonable probability that a properly advised defendant would have accepted a plea offer, despite earlier protestations of innocence.”

The significant disparity between the 10-year sentence Jon was offered and the 24 years he got is very relevant to the prejudice analysis, the Court said. Jon “was not adequately informed that the district court would have been bound by the agreed-upon sentence. Thus, counsel improperly skewed his attention away from the sizeable sentencing disparity he faced in favor of the need for him to personally supply a factual basis… Sentencing disparity is strong evidence of a reasonable probability that a properly advised defendant would have accepted a plea offer, despite earlier protestations of innocence.”

United States v. Kearn, Case No. 23-3029, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 1471 (10th Cir. January 23, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root

End Run: John Ham filed a

End Run: John Ham filed a