We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SCOTUS TO HEAR TWO CRIMINAL FRAUD ARGUMENTS TODAY

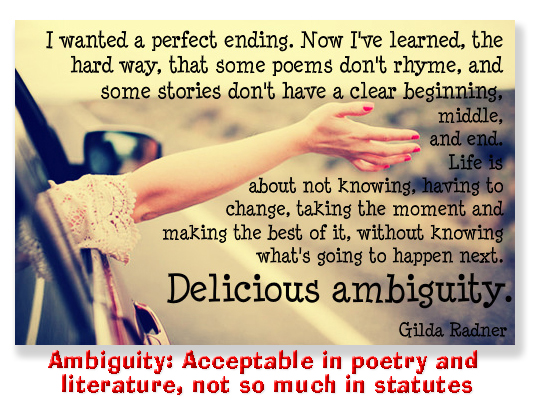

The Supreme Court will hear arguments today on two criminal fraud cases that explore whether people who work privately for government officials owe a duty of honest services to the public under what the Wall Street Journal calls “the ill-defined honest-services fraud statute.”

The Supreme Court will hear arguments today on two criminal fraud cases that explore whether people who work privately for government officials owe a duty of honest services to the public under what the Wall Street Journal calls “the ill-defined honest-services fraud statute.”

In the first case, former state official Joseph Percoco was serving as campaign manager for former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo at the time he accepted a $35,000 payment from a real-estate developer to help obtain government approval for a project. The government declared him to be “functionally a public official” because he had clout with state agencies. Thus, the US Attorney said, Joe committed honest-services fraud.

Joe complained in his Supreme Court brief that the 2nd Circuit’s“functionally a public official” rule could have “sweeping implications not only for lobbyists and donors but also for the family members of public officials, who ‘hold unparalleled access and influence’ and whose ‘independent business interests may be in a position to benefit from state action,'” according to SCOTUSBlog.

The federal prosecutorial approach to fraud has created confusion in lower courts for years. In the last decade, the “right of honest services” has been especially pernicious: nowhere in the statute or a definitive Supreme Court ruling is the “right of honest services” defined. In fact (as Joe has argued), the Supreme Court’s 2010 Skilling v. United States decision and 2016 McDonnell v. United States have pretty much established that bribery laws are “concerned not with influence in the abstract, but rather with the sale of one’s official position.” Private citizens cannot take official action or use their positions to bring about government action, Joe contends, because they have no such positions. Thus, they cannot violate federal fraud laws.

The federal prosecutorial approach to fraud has created confusion in lower courts for years. In the last decade, the “right of honest services” has been especially pernicious: nowhere in the statute or a definitive Supreme Court ruling is the “right of honest services” defined. In fact (as Joe has argued), the Supreme Court’s 2010 Skilling v. United States decision and 2016 McDonnell v. United States have pretty much established that bribery laws are “concerned not with influence in the abstract, but rather with the sale of one’s official position.” Private citizens cannot take official action or use their positions to bring about government action, Joe contends, because they have no such positions. Thus, they cannot violate federal fraud laws.

In Skilling v. United States, the Supreme Court limited criminal liability for fraud to kickback and bribery schemes, but at the time three Justices – Scalia, Thomas and Kennedy – believed the law’s vagueness made it unconstitutional. Lower courts have held that public officials owe a “right of honest services” to their constituents, but the Supreme Court has never ruled that private individuals owe a fiduciary duty to the public.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal complained,

Was Mr. Percoco paid to leverage his political clout? Of course. His simultaneous employment as Cuomo’s campaign manager and a business consultant is certainly sketchy. But the government’s theory… could be used to prosecute any powerful lobbyist, including former lawmakers who don’t act in the putative public interest…This would present First Amendment concerns since citizens have the right to petition their government. It would also impair due process for private citizens who have no way of knowing if they are covered by the honest-services law.

In the second case, the government charged contractor Louis Ciminelli, a Cuomo campaign contributor, with conspiracy to commit fraud by rigging a construction contract for a state-subsidized solar panel plant. A member of a nonprofit overseeing the project drafted the proposal to favor Lou’s construction firm. There was no evidence Lou directed the proposal’s terms, nor that either the state or nonprofit suffered any loss of property as a result of Lou’s firm being chosen.

But the government claimed Lou defrauded the nonprofit of its “right to control its assets” by “exposing it to the risk of economic harm through false representations about the fairness and competitiveness of the bidding process.” Prosecutors did not produce evidence linking Lou to any bribes or kickbacks. Instead, the prosecutors discussed deprivation of a “right to control”: Lou’s deception deprived the nonprofit board of its right to control the funds and the allocation process.”

But the government claimed Lou defrauded the nonprofit of its “right to control its assets” by “exposing it to the risk of economic harm through false representations about the fairness and competitiveness of the bidding process.” Prosecutors did not produce evidence linking Lou to any bribes or kickbacks. Instead, the prosecutors discussed deprivation of a “right to control”: Lou’s deception deprived the nonprofit board of its right to control the funds and the allocation process.”

As the Wall Street Journal put it, “If you’re struggling to understand the government’s convoluted theory, you’re not alone.”

SCOTUSBlog said Lou’s “main wrongdoing appears to be his ‘sneaking to the front of the line’ in the negotiation process. If the Supreme Court continues its trend of narrowing the scope of federal fraud criminalization, it can do so by eliminating the ‘right to control’ theory of fraud.”

Lou has completed his sentence, while Joe is on home confinement. A Supreme Court win won’t give them back the time they served, but their names could be cleared.

Wall Street Journal, The Supreme Court gets a Fraud Test (November 25, 2022)

SCOTUSBlog, A sharp business deal or a federal crime? Justices will review what counts as fraud in government contracting (November 25, 2022)

SCOTUSBlog, Former aide to Andrew Cuomo wants court to narrow scope of federal bribery law (November 27, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root