We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SUPREMES TACKLE FEDERAL SENTENCING ISSUES, THEN BAKE A CAKE

The big news from the Supreme Court yesterday was its masterful dodge-and-weave on whether a Christian baker had to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple in violation of his religious beliefs that gay marriage was morally wrong. The long-awaited opinion, in which the 7-2 Court did not decide the issue but rather concluded that the Colorado state commission that had dinged the baker did so in the wrong way, is covered elsewhere in much more detail than here.

The big news from the Supreme Court yesterday was its masterful dodge-and-weave on whether a Christian baker had to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple in violation of his religious beliefs that gay marriage was morally wrong. The long-awaited opinion, in which the 7-2 Court did not decide the issue but rather concluded that the Colorado state commission that had dinged the baker did so in the wrong way, is covered elsewhere in much more detail than here.

Of interest to us were a pair of decisions, Hughes v. United States and Koons v. United States, with very different issues springing from a common core. We’ll start with Hughes:

CLEARING UP FREEMAN

A number of federal defendants enter into Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1)(C) plea agreements, in which the parties agree to a specific sentence. The district court may accept the deal, in which case the defendant gets the specific sentence he or she bargained for, or it can reject it. If the court rejects the sentence, the whole plea agreement is rejected, and the parties go forward as if there is no deal at all.

These “Type-C” agreements were good for defendants, who did not want to sign a plea agreement that would let the court run wild with whatever sentence it wanted to impose. But then, in 2007, the United States Sentencing Commission started adjusting the drug table downward, and making the changes retroactive. Suddenly, the people with Type-C agreements were shut out of sentence reductions, because their sentences were set pursuant to an agreement, not the Guidelines.

The issue came to the Supreme Court in the 2011 case of Freeman v. United States. The Supreme Court split so badly, with four in the majority, four in the minority and one – Justice Sotomayor – writing a concurring opinion, that no single interpretation or rationale was clear. Some courts of adopted Justice Sotomayor’s reasoning, while others adopted the plurality’s reasoning.

The issue came to the Supreme Court in the 2011 case of Freeman v. United States. The Supreme Court split so badly, with four in the majority, four in the minority and one – Justice Sotomayor – writing a concurring opinion, that no single interpretation or rationale was clear. Some courts of adopted Justice Sotomayor’s reasoning, while others adopted the plurality’s reasoning.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court cleared up the confusion, and in so doing, opened the door to Type-C agreements getting the benefits of 2-level reductions in 2007, 2011 and 2014. A sentence reduction under 18 USC 3582(c)(2) is permissible if the original sentence was “based on” the Guidelines. The Supreme Court held that a sentence imposed pursuant to a Type-C agreement is “based on” the defendant’s Guidelines range so long as that range was part of the framework the district court relied on in imposing the sentence or accepting the agreement.

A district court imposes a sentence that is “based on” a Guidelines range for purposes of Sec. 3582(c)(2) if the range was a basis for the court’s exercise of discretion in imposing a sentence. “Given the standard legal definition of ‘base’,” the Court said today, “there will be no question in the typical case that the defendant’s Guidelines range was a basis for his sentence. A district court is required to calculate and consider a defendant’s Guidelines range in every case under 18 USC 3553(a). Indeed, the Guidelines are “the starting point for every sentencing calculation in the federal system.” Thus, the Court ruled, “in general, Sec. 3582(c)(2) allows district courts to reconsider a prisoner’s sentence based on a new starting point — that is, a lower Guidelines range — and determine whether a reduction is appropriate.

The Government and the defendant may agree to a specific sentence in a Type-C agreement, but the Sentencing Guidelines prohibit district courts from accepting Type-C agreements without first evaluating the recommended sentence in light of the defendant’s Guidelines range. So in the usual case the court’s acceptance of a Type-C agreement and the sentence to be imposed pursuant to that agreement are “based on” the defendant’s Guidelines range.

The Government and the defendant may agree to a specific sentence in a Type-C agreement, but the Sentencing Guidelines prohibit district courts from accepting Type-C agreements without first evaluating the recommended sentence in light of the defendant’s Guidelines range. So in the usual case the court’s acceptance of a Type-C agreement and the sentence to be imposed pursuant to that agreement are “based on” the defendant’s Guidelines range.

The Court said its interpretation furthers the purposes of the Sentencing Reform Act, and confirms prior holdings in Molina-Martinez v. United States and Peugh v. United States that the Guidelines remain a basis for almost all federal sentences.

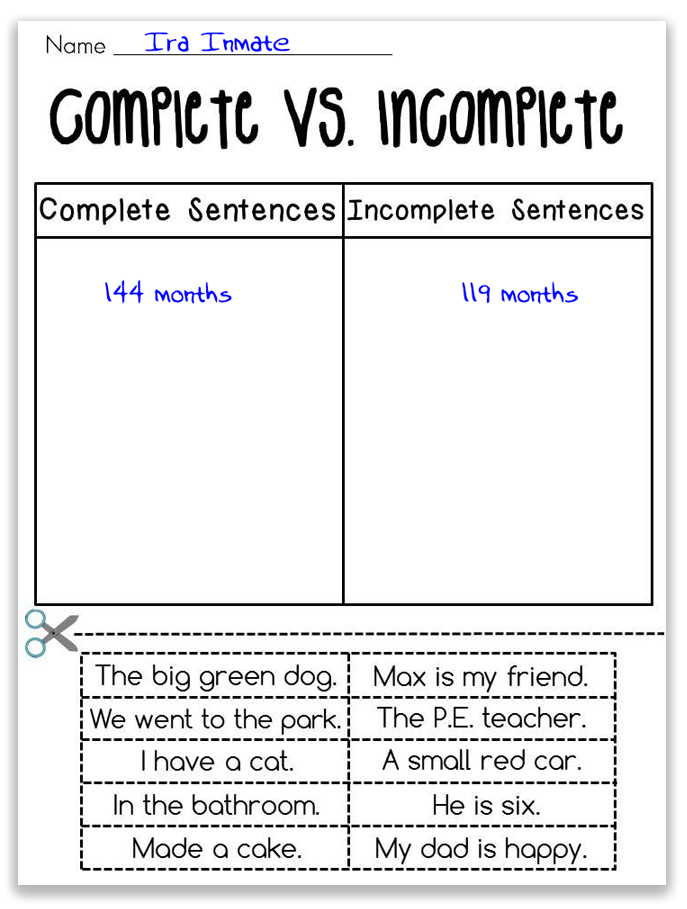

Thus, the Court said, petitioner Erik Hughes is eligible for relief under Sec. 3582(c)(2). The District Court accepted his Type-C agreement after concluding that a 180-month sentence was consistent with the Guidelines, and then calculated Hughes’ sentencing range and imposed a sentence it deemed “compatible” with the Guidelines. The sentencing range was thus a basis for the sentence imposed. And because that range has since been lowered by the Commission, the district court has the discretion to decide whether to reduce Hughes’ sentence after considering the 18 USC 3553(a) sentencing factors and the Sentencing Commission’s relevant policy statements.

WYSIWYG

The Court was unanimous and brief in Koons v. United States.

There is an interplay between statutory mandatory minimum sentences and Guidelines. We see it often. A defendant has an advisory Guideline range of 33-41 months for a drug offense, but because she was charged with trafficking in 30 grams of cocaine base, a mandatory minimum sentence of 60 months is prescribed by 21 USC 841(b)(1)(B)(iii). The Guidelines specify that when a statutory minimum sentence is higher than the top end of the advisory Guidelines range, the advisory Guidelines range is considered to be a minimum and maximum of 60 months.

There is an interplay between statutory mandatory minimum sentences and Guidelines. We see it often. A defendant has an advisory Guideline range of 33-41 months for a drug offense, but because she was charged with trafficking in 30 grams of cocaine base, a mandatory minimum sentence of 60 months is prescribed by 21 USC 841(b)(1)(B)(iii). The Guidelines specify that when a statutory minimum sentence is higher than the top end of the advisory Guidelines range, the advisory Guidelines range is considered to be a minimum and maximum of 60 months.

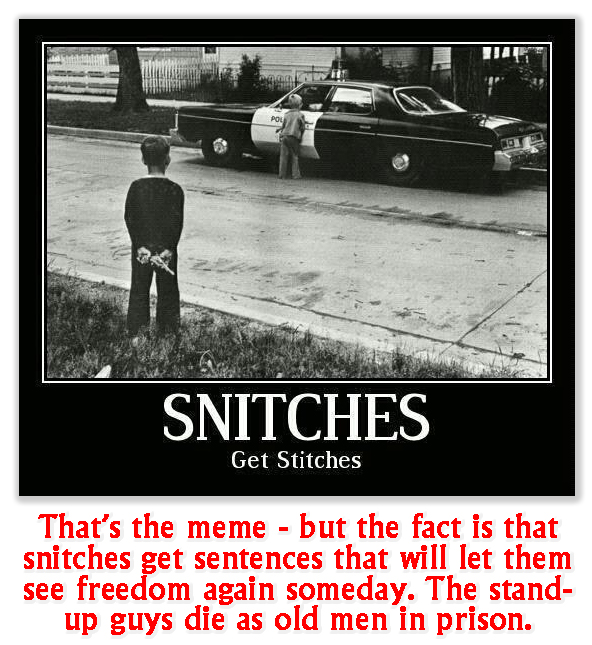

When a defendant is saddled with a mandatory minimum sentence, there is nothing that will trump the minimum other than cooperation with the government (or in rare cases, a “safety valve” sentence under 18 USC 3553(f)). That’s a principal reason that everyone cooperates: it’s one thing to declare oneself a “stand up” guy who won’t rant out co-conspirators over a couple of beers with buddies, but it’s another thing entirely to serve 20 years in a beerless federal prison while those same friends are at home quaffing brews.

Under 18 USC 3582(c)(2), a defendant is eligible for a sentence reduction if she was initially sentenced “based on a sentencing range” that was later lowered by the United States Sentencing Commission. The five defendants in Koons claimed to be eligible for a reduced sentence in the wake of the Sentencing Commission’s 2014 reduction of the drug quantity tables. The defendants were convicted of drug offenses that carried statutory mandatory minimum sentences, but they received sentences below these mandatory minimums, because they “substantially assisted” the Government in prosecuting other drug offenders within the meaning of 18 USC 3553(e).

Under 18 USC 3582(c)(2), a defendant is eligible for a sentence reduction if she was initially sentenced “based on a sentencing range” that was later lowered by the United States Sentencing Commission. The five defendants in Koons claimed to be eligible for a reduced sentence in the wake of the Sentencing Commission’s 2014 reduction of the drug quantity tables. The defendants were convicted of drug offenses that carried statutory mandatory minimum sentences, but they received sentences below these mandatory minimums, because they “substantially assisted” the Government in prosecuting other drug offenders within the meaning of 18 USC 3553(e).

The Supreme Court held that the defendants’ sentences were “based on” the statutory mandatory minimum and on their substantial assistance to the Government, not on sentencing ranges that the Sentencing Commission later lowered. In other words, what you see is what you get – no pretending that the beneficial sentence for helping out ol’ Uncle Sugar was based on the Sentencing Guidelines rather than on you saving your own skin.

Therefore, the Koons defendants were ineligible for Sec. 3582(c)(2) sentence reductions.

Hughes v. United States, Case No. 17-155 (Supreme Court, June 4, 2018)

Koons v. United States, Case No. 17-5716 (Supreme Court, June 4, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root