We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

MY LAWYER IS A M*****F*****

There is an old riddle asking the difference between a lawyer and a rooster. The answer, of course, is that a rooster clucks defiance.

Defendants often complain that their lawyers screwed them. Seldom is there a case where everyone else complains that defense counsel screwed the defendant’s mother… and means that in the most literal sense.

Defendants often complain that their lawyers screwed them. Seldom is there a case where everyone else complains that defense counsel screwed the defendant’s mother… and means that in the most literal sense.

Johnathan DeLaura had a serious problem, having been charged with multiple child pornography counts after being caught in a “sting” that left him on the losing side of a mountain of evidence. Johnathan’s mother, who undoubtedly believed in her son’s innocence, located lawyer Gary Greenwald and made the fee deal: she paid Gary a $25,000 retainer against future work and he began representing Johnathan.

The “horizontal fee” is an infamous legend in the legal profession, if not in the plush offices of the white-shoe law firms, then certainly in the shabby corridors of sole practitioners who survive on court appointments and the occasional paying client. A “horizontal fee,” of course, is payment for legal services exacted by the lawyer in a horizontal and unclothed position, that is to say, payment in sex instead of in money.

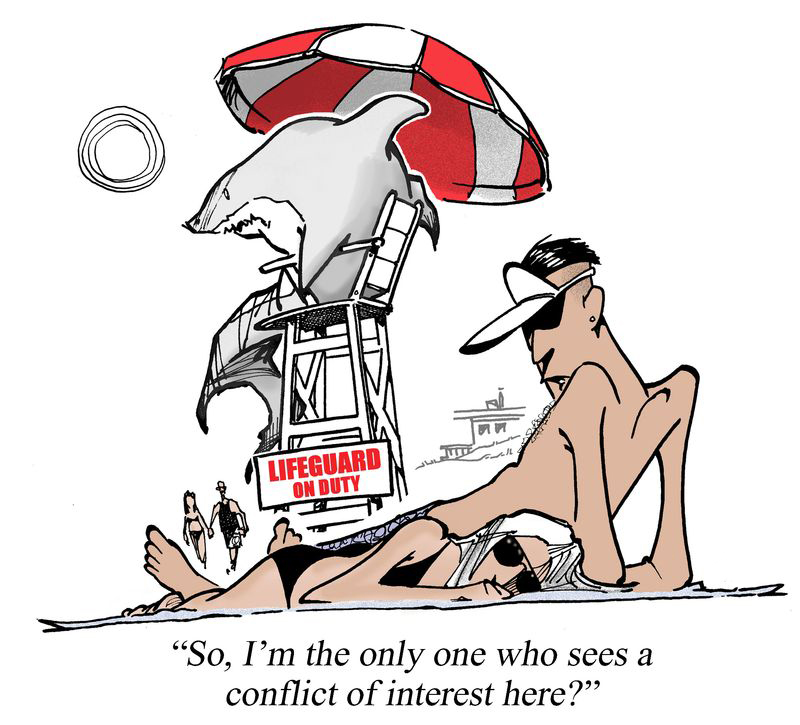

Sometime after Gary began representing Johnathan, the U.S. Attorney’s Office had reason to believe that the lawyer was having a sexual affair with Johnathan’s mother. No one knows for sure whether such an affair occurred (except for Gary and Mom). If their sexual tryst happened at all, it began when Mom hired Gary and ended a few months later, right about the time Johnathan took a plea deal.

The prosecutor confronted Gary with his suspicions. Gary coyly answered some questions but refused to answer others, leaving the Assistant U.S. Attorney believing that Gary “certainly suggested to us that the information that we had received was, was correct.” The conversation led the prosecutors to believe that Gary had forgiven “significant legal fees” in connection with the relationship. The classic “horizontal fee.”

The prosecutor confronted Gary with his suspicions. Gary coyly answered some questions but refused to answer others, leaving the Assistant U.S. Attorney believing that Gary “certainly suggested to us that the information that we had received was, was correct.” The conversation led the prosecutors to believe that Gary had forgiven “significant legal fees” in connection with the relationship. The classic “horizontal fee.”

The AUSA reported his suspicions to the district court, telling the judge he believed there was a potential conflict, that the conflict was personal and sensitive, that Gary denied any conflict, that a hearing on the conflict was necessary, and that Johnathan should have independent counsel to advise him on the conflict.

The judge called the prosecutor and Gary into chambers, and asked Gary about the allegation in what the Court of Appeals called “an eyebrow-raising colloquy.” Gary refused to answer the judge’s questions, and suggested the judge instead deduce the answers from the plot of an underperforming 2000 movie named The Contender. The appalled judge, said: “You won’t deny it. You won’t deny it. You want to invoke a movie, that’s fine. So let’s have the hearing.”

At the hearing, the district court appointed another lawyer to give Johnathan independent advice, and the government explained its concerns. Gary again refused to answer questions about his relationship, if any, with Johnathan’s mother. This put the court in a quandary, because the law requires that – which a conflict of interest charge is leveled – the court first has an “inquiry” obligation, to investigate the facts in order to determine whether the attorney in fact suffers from an actual conflict, a potential conflict, or no genuine conflict at all. Only then is there to be a hearing at which the defendant may waive the conflict (if possible) or ask for new counsel.

The district court did what it could, and during the hearing asked Johnathan if he wanted to waive the conflict, assuming for the sake of argument that there even was a conflict. Johnathan said he would waive the conflict, but employed enough logic to knot a pretzel stick:

If a sane person were to listen to this and say the allegation is true, then logically they would know that there obviously is a conflict and they would never accept anything. They would throw this away… [T]o state to me “okay, you have to assume that this is true and then make a decision upon that,” well, logic would, would–you know, it would be illogical to continue if it were true.

The court reluctantly accepted this “waiver” and went forward. Ultimately, Johnathan got a 400-month sentence.

After reflecting on the reality of what a 35-year sentence meant, Johnathan appealed – now represented by a different lawyer – alleging that Gary had a conflict of interest (and that his deal with the government gained him nothing). Meanwhile, Gary died, meaning that he is likely to be only marginally less forthcoming in any future testimony. Two days ago, the 2nd Circuit – clearly troubled by the whole affair – turned down his appeal, while virtually assuring him of a hearing on any forthcoming 2255 motion.

After reflecting on the reality of what a 35-year sentence meant, Johnathan appealed – now represented by a different lawyer – alleging that Gary had a conflict of interest (and that his deal with the government gained him nothing). Meanwhile, Gary died, meaning that he is likely to be only marginally less forthcoming in any future testimony. Two days ago, the 2nd Circuit – clearly troubled by the whole affair – turned down his appeal, while virtually assuring him of a hearing on any forthcoming 2255 motion.

So, assuming the fact as alleged are right, what might the conflict be? The Circuit accepted the government’s analysis:

(1) because his relationship with Mom ended, Gary might bear a grudge against Johnathan or might want to spend as little time with him as possible;

(2) given the ethical and personal problems with the relationship, Gary might have an interest in rolling over for the prosecution, in order to persuade the government not to report him to the disciplinary committee; or

(3) the fee arrangement may have been based on the relationship, so that when Gary was no longer scoring with Mom, he might just want to end the representation quickly knowing he wasn’t going to be paid anything more.

The appellate panel framed the problem as this: If the waiver is valid, Johnathan has no claim. But if the waiver is invalid – either because the conflict is unwaivable, because it was not knowing and intelligent, or because the district court failed to make the required inquiry – then the Circuit has to consider the underlying conflict claim itself. If the conflict were potential, Johnathan would have to show it somehow prejudiced him. If the conflict were actual, however, he would only have to make the lesser showing of adverse effect.

The 2nd complained that “this record allows us to answer few of those questions. We do not know whether there was a sexual relationship (or its timing, duration, or terms), whether a conflict arose from it, whether that conflict was so severe as to be unwaivable, or whether DeLaura was harmed by it. An evidentiary hearing would be needed to sort this out. Because the Supreme Court has expressed a preference for resolving ineffectiveness claims on collateral review… we affirm the conviction rather than remand the case to the district court. But in the event DeLaura’s new attorney files a habeas petition, we think an evidentiary hearing may be in order and that DeLaura’s ineffectiveness claim would merit searching evaluation.”

The 2nd complained that “this record allows us to answer few of those questions. We do not know whether there was a sexual relationship (or its timing, duration, or terms), whether a conflict arose from it, whether that conflict was so severe as to be unwaivable, or whether DeLaura was harmed by it. An evidentiary hearing would be needed to sort this out. Because the Supreme Court has expressed a preference for resolving ineffectiveness claims on collateral review… we affirm the conviction rather than remand the case to the district court. But in the event DeLaura’s new attorney files a habeas petition, we think an evidentiary hearing may be in order and that DeLaura’s ineffectiveness claim would merit searching evaluation.”

The Circuit’s deferral of the question is unremarkable. The same, however, cannot be said of the facts. We are puzzled that the district court did not call Mom to the stand during the hearing and ask her. Whatever the reason, Mom’s visits to her son must be pretty interesting.

United States v. DeLaura, Case No. 14-1204 (2nd Cir., June 5, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root