We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

MY BAD… BUT YOU’RE STILL SCREWED

Steve Schenian pled guilty to drug trafficking charges. As he approached his sentencing date, Steve – who had done a lot of sampling of his illegal wares – decided to change his ways.

No surprise there. A lot of defendants experience what is colloquially known as a “jailhouse conversion.” Most defendants’ claims that they’ve cleaned up their act lasts until they’re released, if that long. A few don’t even make it to sentencing. And the judges – who have heard it all before – usually don’t buy it.

Steve had convinced his girlfriend to smuggle some drugs to him in jail, but he later told the probation officer writing his Presentence Report that he had given that up, that he wanted to “turn his life around.” Unfortunately for Steve, the government ratted him out: a urine sample collected the evening before sentencing showed that he had one illegal drug in his system.

When imposing sentence the judge did not mention the previous night’s test but did deem it significant that Steve had continued using drugs while in custody. The judge rejected Steve’s sentencing proposal, and went with the government’s recommended 144 months.

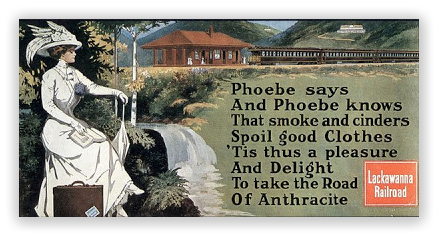

The drug test was especially unfortunate for Steve, because – while the results were accurate – the prosecutor was not. He had misinterpreted raw data from the test, which, if read correctly, would show Steve was as clean as Phoebe Snow. Eight days after Steve’s sentencing, the prosecutor sent letters to the court and Steve’s lawyer disclosing the error.

The district court promptly issued an order saying that it “has considered the correction of information conveyed in the [government’s]… letter. The Court remains convinced that the original sentence imposed in this case was sufficient but not greater than necessary to accomplish the purpose of sentencing. None of the facts contained in that letter would lead the Court to alter its decision.”

The district court promptly issued an order saying that it “has considered the correction of information conveyed in the [government’s]… letter. The Court remains convinced that the original sentence imposed in this case was sufficient but not greater than necessary to accomplish the purpose of sentencing. None of the facts contained in that letter would lead the Court to alter its decision.”

Steve nevertheless moved for resentencing under Fed.R.Crim.P. 35(a), which lets a district court correct a sentence within 14 days after sentencing, when the original sentence “resulted from arithmetical, technical, or other clear error.” The district court denied his motion.

Earlier this week, the 7th Circuit agreed. It held that if the district judge thought the sentence had been influenced by a false belief that Steve was on drugs the night before sentencing, that belief would have been a “clear error” that would have allowed the judge to fix the problem. The Circuit said “a mistakenly high sentence cannot be called an “arithmetical” or “technical” gaffe, but an error it would be – and if the error was clear only in hindsight, still it would be ‘clear error’.” After all, the appellate court said, the purpose of Rule 35(a) is to let judges “fix errors that otherwise would be bound to produce reversal.”

Steve’s problem, the Circuit said, “is that the district judge did not rely on the false information, so there was no judicial error. The prosecutor made an error, and that error was clear in retrospect (once the lab released its report). But Rule 35(a) does not authorize a judge to revise a sentence because one of the litigants has made a mistake. It authorizes the court to fix sentences affected by its own errors, whether they be arithmetical, technical, or otherwise “clear”. Once a judge has decided that the sentence is unaffected by error, there is no need for a do-over.”

While we would be the last to suggest that district judge cannot be taken at his or her word, it taxes credulity that a district court sentencing a drug-dealing defendant who had professed a “jailhouse conversion” to clean living would not be influenced by finding out the guy standing in front of the judge was stoned. The Circuit complained that “a remand for further proceedings would waste everyone’s time,” but this seems a case where the public’s confidence in the integrity of the criminal process would be served by resentencing in front of a different judge (which is the course followed when the government breaches a plea agreement by providing information at sentencing it promised not to).

The government was wrong in its claim, perhaps negligently or recklessly. But regardless of degree of fault, the defendant was sandbagged by a claim that was not only false, but one he had neither the time nor the resources to address.

United States v. Schenian, Case No. 16-3132 (7th Cir., Jan. 30, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root