We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LET’S MAKE A DEAL

Bad, bad Leo Brown… Well, maybe not so bad, but in bad trouble. In October 2016, Edwin Leo Brown was indicted on four counts of possession with the intent to distribute crack cocaine and a fifth count for being an 18 USC § 922(g)(1) felon in possession (F-I-P) of a gun. Leo was looking at a maximum sentence of 20 years’ imprisonment on each of the four drug charges, and up to 10 more on the F-I-P count.

Bad, bad Leo Brown… Well, maybe not so bad, but in bad trouble. In October 2016, Edwin Leo Brown was indicted on four counts of possession with the intent to distribute crack cocaine and a fifth count for being an 18 USC § 922(g)(1) felon in possession (F-I-P) of a gun. Leo was looking at a maximum sentence of 20 years’ imprisonment on each of the four drug charges, and up to 10 more on the F-I-P count.

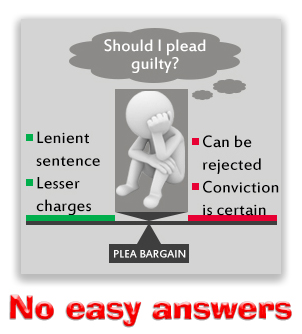

Leo’s lawyer, Frank Harper, negotiated with the government, ultimately getting two plea agreements—one of which called for Leo to cooperate with the Feds and one of which did not—that both called for Leo to plead guilty only to the F-I-P count. That meant that taking either deal would limit Leo’s sentence to ten years. Harper advised Leo that he should take one of the plea agreements or the other, but Leo was skeptical. When Leo told Harper that he felt like the lawyer could have gotten him a better deal than 10 years, Harper apparently responded in exasperation, “It’s not my fault why you’re facing ten years.”

That offended Leo, who “from that moment” did not “trust [Harper’s] judgment” and told him so. The relationship deteriorated, and Harper subsequently withdrew as counsel.

Enter affable lawyer Brett Wentz. Leo liked Wentz, who agreed that Leo would face a firm sentence of 10 years if he took either plea deal, but told him that even if he did not–instead just entering an “open plea” to all counts without any–Leo’s sentencing guideline range would be the same. “In other words,” as the 4th Circuit described it, “Wentz advised Brown that he would be facing a statutory maximum of ten years’ imprisonment regardless of whether he accepted a plea offer or not.”

Leo really wanted to preserve his right to appeal, which he would have to waive under either version of the plea agreement. So after Wentz told him he’d get no more than 10 years with or without a plea deal, Leo thought it was a no-brainer. He rejected the plea offers and entered a guilty plea to all counts without benefit of a plea agreement.

At his change-of-plea hearing, the judge told Leo that he faced up to 20 years’ imprisonment on each of the four drug charges. At that point, Leo and lawyer Wentz conferred off the record. Leo then told the court he understood the penalties. The judge proceeded to tell Leo that he faced 10 years on the F-I-P. Leo again talked to Wentz off the record before telling the court he understood that potential penalty, too.

At his change-of-plea hearing, the judge told Leo that he faced up to 20 years’ imprisonment on each of the four drug charges. At that point, Leo and lawyer Wentz conferred off the record. Leo then told the court he understood the penalties. The judge proceeded to tell Leo that he faced 10 years on the F-I-P. Leo again talked to Wentz off the record before telling the court he understood that potential penalty, too.

Unless there’s a plea deal that requires a particular sentence, the judge always tells a defendant during a change-of-plea hearing that even if defense counsel had given him an estimate of what the sentence might end up being, that estimate is not binding on the court. Leo’s judge told him this, but Leo “affirmed that he understood and subsequently entered an open guilty plea as to all five counts.”

You can see where this is headed, but Leo couldn’t. At sentencing a few months later, the court hammered Leo with 210 months’ imprisonment—17½ years—on all counts, an upward departure from the advisory guideline sentencing range of 87 to 108 months. Leo was not pleased.

After his sentence was affirmed on appeal, Leo filed a 28 USC § 2255 post-conviction motion arguing that Wentz provided ineffective assistance in giving Leo wrong advice on taking the plea deal.

Relying on the Supreme Court decision in Lee v. United States, the district court ruled that it would “not upset a plea solely because of post hoc assertions from a defendant about how he would have pleaded but for his [counsel’s] deficiencies.” Instead, it would look to “contemporaneous evidence to substantiate a defendant’s expressed preferences.” Based on the record, the district judge found, “even if Wentz had properly advised Brown about his sentencing exposure… Brown would not have signed the non-cooperation plea agreement with an appellate waiver and pleaded guilty to count five pursuant to the plea agreement” because avoiding having to “waivi[e] his right to appeal was more important to Brown than his sentencing exposure.”

On Tuesday, the 4th Circuit reversed the judgment, holding that Lee was the wrong standard to apply and that Leo had “demonstrated a reasonable probability that, but for Wentz’s erroneous advice regarding sentence exposure, he would have accepted the government’s offer.”

The 4th held that “the biggest distinction” between Lee and Leo’s case “is that Lee concerned an individual who accepted a guilty plea offer, while the instant appeal concerns an individual who rejected a guilty plea offer.” The Circuit said that the proper standard where a plea deal is rejected is set out in Missouri v. Frye and Lafler v. Cooper, a pair of Supreme Court decisions from 2012 that “articulated a different way to show prejudice” where a plea deal is not accepted, which is the issue in Leo’s case.

A defendant who argues he rejected a plea offer because of ineffective assistance of counsel “need not present contemporaneous evidence to support his ineffective assistance claims,” the 4th Circuit said. Instead, a reasonable probability that a defendant would have accepted the plea offer but for counsel’s bad advice was met here by Leo’s testimony that he “would have taken the plea that the Government offered [him]” had he known he was facing a theoretical maximum of 90 years’ imprisonment, and that he believed, based on Wentz’s advice, that his “maximum exposure” when he pleaded to all five counts was “[n]o more than ten years.” The very fact that Leo pled guilty to more serious charges—namely, receiving 17.5 years’ imprisonment when the government’s plea offer offered a max of 10 years—was alone enough to show a “reasonable probability” Leo would have taken the deal, the Circuit said.

A defendant who argues he rejected a plea offer because of ineffective assistance of counsel “need not present contemporaneous evidence to support his ineffective assistance claims,” the 4th Circuit said. Instead, a reasonable probability that a defendant would have accepted the plea offer but for counsel’s bad advice was met here by Leo’s testimony that he “would have taken the plea that the Government offered [him]” had he known he was facing a theoretical maximum of 90 years’ imprisonment, and that he believed, based on Wentz’s advice, that his “maximum exposure” when he pleaded to all five counts was “[n]o more than ten years.” The very fact that Leo pled guilty to more serious charges—namely, receiving 17.5 years’ imprisonment when the government’s plea offer offered a max of 10 years—was alone enough to show a “reasonable probability” Leo would have taken the deal, the Circuit said.

The Circuit ordered the case remanded and that Leo be offered the original 10-year deal.

United States v. Brown, Case No. 22-7105, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 12211 (4th Cir. May 20, 2025)

Lee v. United States, 582 U.S. 357 (2017)

Missouri v. Frye, 566 U.S. 134 (2012)

Lafler v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 156 (2012)

– Thomas L. Root