We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

IF YOU SEE SOMETHING, SAY SOMETHING

It’s hard to keep track of how many people get tripped up because their lawyers – who normally never shut up – fail to speak up when an objection is warranted.

It’s hard to keep track of how many people get tripped up because their lawyers – who normally never shut up – fail to speak up when an objection is warranted.

The result of counsel’s reticence is that the appeals court would only review for plain error, and proving F.R.Crim.P. 52(b) plain error is hard to do.

Nathaniel Acevedo-Osorio had sexual contact with a 15-year-old girl at his boxing gym. He had sex with her many times and used coercion to stalk her and force her to send him sexually explicit photos. The abuse went on for four years before Nat was arrested. It was pretty ugly, but if you want details, click on the link to the decision.

Nat’s lawyer cut the deal of the century, getting the government to agree to recommend a 120-month sentence, the mandatory minimum, in a plea agreement that glossed over much of the uglier facts. The presentence report wasn’t so rosy, however, reciting the details of the years-long offense and setting the Guidelines sentencing range at 292-365 months.

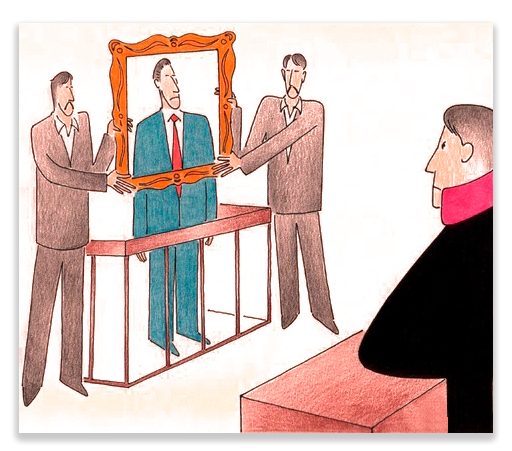

At sentencing, Nat’s lawyer emphasized his client’s turbulent upbringing, the recent murder of his brother, and his family’s support, and she put the mothers of his kids and his boxing coach on the stand to testify to his good character. Counsel pointed to Nat’s having to do some state time because of a probation violation and having to register as a sex offender as reasons to accept the jointly recommended 120-month sentence.

The government offered only the following argument: “Good morning, Your Honor. On behalf of the Government, we would be recommending 120 months pursuant to the plea agreement. Thank you.”

Inexplicably, Nat’s lawyer did not object to the government’s milquetoast recommendation. The district judge hammered Nat with 292 months and 15 years of supervised release (not that I’m complaining that it was uncalled for… Again, read the facts in the decision if you think I’m being draconian).

Inexplicably, Nat’s lawyer did not object to the government’s milquetoast recommendation. The district judge hammered Nat with 292 months and 15 years of supervised release (not that I’m complaining that it was uncalled for… Again, read the facts in the decision if you think I’m being draconian).

Last week, the 1st Circuit held that the government violated the plea agreement but upheld the sentence anyway.

The government may breach a plea agreement by doing something that it promised not to do (such as promising to make no sentencing recommendation but making one anyway) or by failing to do something that it promised to do (such as promising to oppose a Guideline adjustment but then not doing). Even when the government is in “technical compliance” with the plea agreement, the government may not merely pay “lip service” to the plea agreement. A plea agreement has an implied obligation of good faith and fair dealing. As the 1st Circuit put it, “The defendant is entitled to both the benefit of the bargain struck in the plea deal and to the good faith of the prosecutor.”

Generally the government has no implied duty to explain a plea deal’s recommended sentence. Nevertheless, the 1st said that “the government may be obliged to offer some minimal explanation in the rare circumstance in which the parties agree to jointly recommend a sentence that amounts to such a dramatic downward variation that, without some justification by the government, the district court [would be] left to speculate about what rationale might reasonably support such a seemingly off-kilter, well-below guidelines recommendation.”

Here, the Circuit said, the 14-year difference between what the government agreed to and what the Court gave Nat “leads us to conclude that… the government’s failure to provide at least some explanation for its decision to lend its prestigious imprimatur to such a dramatic downward variation likely caused the district court to view the government’s ‘stand by’ statement as just hollow words, undermining any notion that the government viewed the plea agreement as fair and appropriate… In short, Nat did not get what he bargained for: a sentencing hearing in which an inevitably skeptical court could at least comprehend why, in the government’s view, the sentence was proper.”

Nevertheless, the 1st said, because Nat’s lawyer did not object to the government’s mumbled recommendation at sentencing, plain error review applied, and “we cannot conclude that the error was indisputable in light of controlling law.”

Nevertheless, the 1st said, because Nat’s lawyer did not object to the government’s mumbled recommendation at sentencing, plain error review applied, and “we cannot conclude that the error was indisputable in light of controlling law.”

Nat lost his appeal because his lawyer didn’t say something when the government whiffed on its obligation. Still, he has a great 28 USC § 2255 issue.

Some consolation.

United States v. Acevedo-Osorio, Case No. 21-1708, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 24236 (1st Cir. September 24, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root