We’re still doing a weekly newsletter… we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way…

CHOOSING PRISON

One of our favorite television shows back in the 80s was the short-lived Sledge Hammer!, a comedic takeoff about an over-the-top San Francisco cop (obviously modeled on Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry Callahan).

One of our favorite television shows back in the 80s was the short-lived Sledge Hammer!, a comedic takeoff about an over-the-top San Francisco cop (obviously modeled on Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry Callahan).

Among Inspector Sledge’s favorite observations was his thesis that “criminals have no rights: they give up their rights when they choose to become criminals.”

Well, life has always imitated that piece of art where inmates’ child support obligations are concerned. States generally adhere to the rule that voluntary unemployment is not a reason to reduce child support. That makes sense. But courts also reason that commission of a crime is a voluntary act, and incarceration is a logical and foreseeable consequence of committing a crime. Because “A” is voluntary, and “B” is the logical and foreseeable result of “A”, the states conclude therefore that “C” – going to prison – must be a voluntary act, too, the moral equivalent to quitting a job. Thus, inmates must suffer letting the child-support meter run wild while they’re in prison.

And suffer they do. A 2010 government survey found 51,000 federal prisoners –one out of four in the system – have child support orders, with over half of those inmates behind on payments, owing an average of about $24,000.

So, to channel Sledge Hammer, criminals choose to go to prison. If they’re released with a $24,000 debt hanging over them, so what?

The “voluntary prison” rule against child-support modification is as deeply flawed as it is superficially appealing. The notion of criminal conduct – especially breaking federal laws – being a voluntary choice of the criminal underclass is a myth. It was best put by Judge Alex Kozinski of the 9th Circuit in his 2009 essay You’re (Probably) A Federal Criminal: “Most Americans are criminals, and don’t know it, or suspect that they are but believe they’ll never get prosecuted.” His point? Currently, there are nearly 5,000 federal criminal statutes and over 30,000 criminal regulatory offenses in the Code of Federal Regulations. Breaking federal law is as easy as getting out of bed in the morning.

For example, 52% of all Americans 18 to 25 have possessed marijuana at least once, and 46% of all Americans over 25 have done the same. By the simplistic reckoning of the “voluntary prison” syllogism, each of these people has voluntarily committed a felony (violation of 21 USC 844) and each thus has a reasonable expectation of incarceration as a result. Although federal prosecution for simple drug possession is rare, it can happen any time at the government’s discretion. And that is precisely Judge Kozinski’s point.

What’s more, contrary to the supposition that criminals can reasonably expect prison to follow crime, that is hardly true. Beyond the fact that 23.4 million people over the age of 18 committed the federal offense of drug possession, but only 108 people were prosecuted for it, national crime statistics show that the likelihood that crime will lead to punishment is way less than certain. A person who commits murder has a 37.5% chance of not being prosecuted. A rapist has a 60.0% chance of not being prosecuted. A robber has a 72.1% chance of not being prosecuted. And for job security, nothing beats burglary, which has an 87.3% chance of not being solved.

There simply are no data to support the theory that someone who commits a crime in the United States has reason to believe that he or she will be locked up. Some may, others may not, but – like the question of whether unemployment is voluntary – it is a question of fact, not one of law.

So what is the effect of the “voluntary prison” child-support rule? Prisoners who were diligent at paying child support before being locked up are deeply in debt when they are released, and suffer the same loss of licenses and government services reserved for deadbeat dads who never left the street. In addition to the stigma associated with being an ex-con, a released offender owing past-due child support is hobbled by denial of the basics needed to be re-established as a productive member of society. Why punish a guy for five years when you can do it for a lifetime?

So what is the effect of the “voluntary prison” child-support rule? Prisoners who were diligent at paying child support before being locked up are deeply in debt when they are released, and suffer the same loss of licenses and government services reserved for deadbeat dads who never left the street. In addition to the stigma associated with being an ex-con, a released offender owing past-due child support is hobbled by denial of the basics needed to be re-established as a productive member of society. Why punish a guy for five years when you can do it for a lifetime?

There’s a reason for our rant. On Monday, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families announced some sanity, new rules that will requires state child support to ensure that child support orders – the amount noncustodial parents are required to pay each month – reflect the parent’s ability to pay. Tucked into that rule is reform of the “voluntary prison” rule.

The new regs require that prisoners be allowed to seek to lower the amount of child support they pay while in prison. This is not just a bone thrown to prisoners, but rather one that studies show will ultimately increase support payments for kids. “Orders often go unpaid when they are set beyond the ability of unemployed and low-wage parents to pay them, resulting in large arrearages that themselves lead to less employment and support paid. The rule is intended to ensure that all families receive the support they need,” Vicki Turetsky, Commissioner, HHS Office of Child Support Enforcement, said in a statement.

Under the new rules, states will no longer be allowed to treat incarceration as “voluntary unemployment.” States will also be required to notify both parents of the right to seek changes to child support payments if one of the parents is incarcerated for more than six months.

No one knows whether the new rule will face opposition from incoming Republican President Donald Trump or the Republican congress. While some lawmakers have opposed the regulations, arguing they would allow parents to avoid their financial responsibilities, it may be that the issue is too small to be able to compete with all of the other issues facing the new Congress and President.

Reuters, Obama administration revamps child support rules for prisoners (Dec. 19, 2016)

U.S. Dept. Health & Human Services, New rule will increase regular child support payments to families (Dec. 19, 2016)

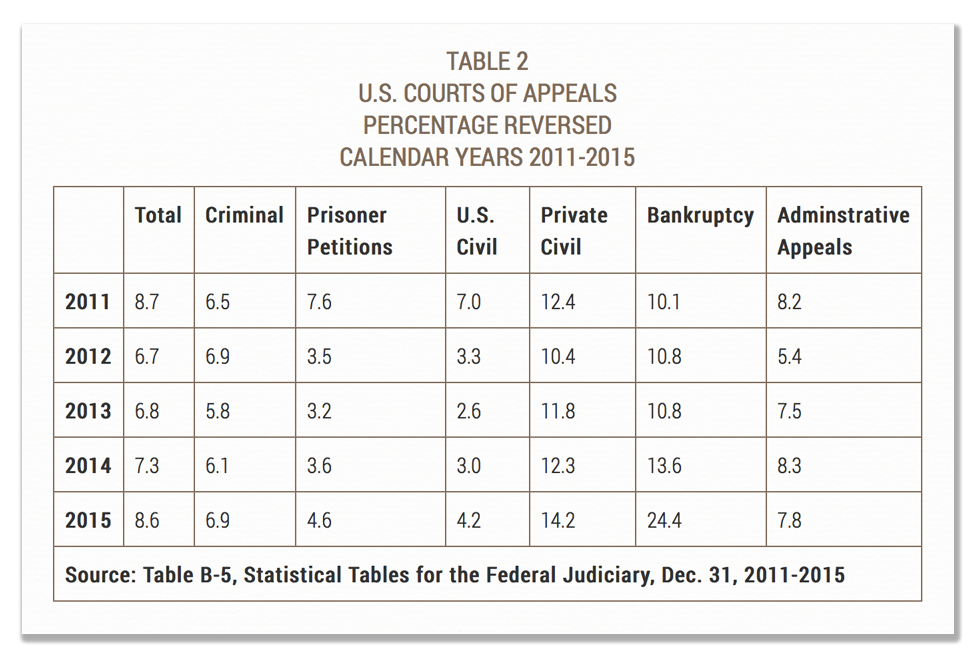

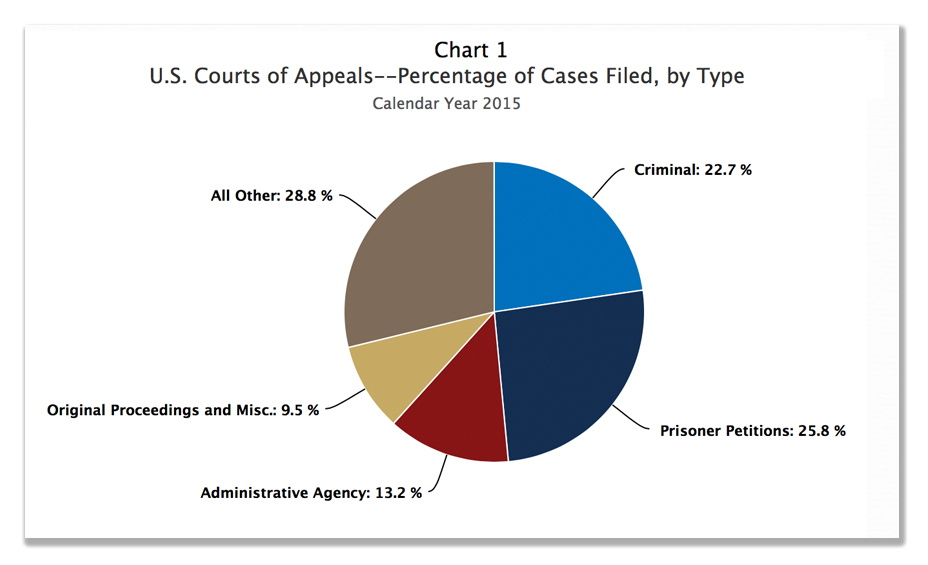

The increase in direct criminal appeals, according to the JDAO, was fueled by drug cases, mostly for drugs other than marijuana. This suggests either

The increase in direct criminal appeals, according to the JDAO, was fueled by drug cases, mostly for drugs other than marijuana. This suggests either