Vol. 2, No. 31

Vol. 2, No. 31

This week:

Supreme Court to Decide Whether Johnson Applies to Guidelines “Career Offender”

Mathis Says It Does Not Really Matter What You Did

Back To School Time

Have You Stopped Beating Your Wife Yet?

High Livin’ in the Old Dominion

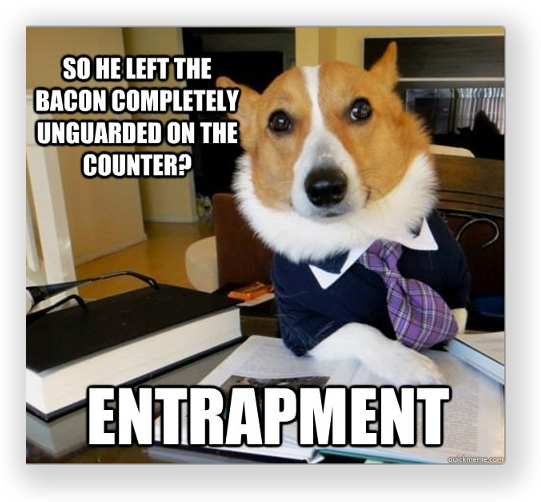

Sob Story

Former AUSA Writes Confessional

Sentencing Reform Bill Would Authorize Assigning ‘Risk Scores’ To Inmates

Sentencing Reform – Even FAMM Is Giving Up?

SUPREME COURT TO DECIDE WHETHER JOHNSON APPLIES TO GUIDELINES “CAREER OFFENDER”

The Courts of Appeal are badly divided on whether Johnson v. United States applies retroactively to collateral cases challenging federal sentences enhanced under the residual clause in Guideline § 4B1.2(a)(2) (defining “crime of violence”).

Today, the Supreme Court decided to answer the question. The Court granted certiorari to a case in which the 11th Circuit denied a petitioner the right to challenge his ‘career offender’ status under Johnson.

Today, the Supreme Court decided to answer the question. The Court granted certiorari to a case in which the 11th Circuit denied a petitioner the right to challenge his ‘career offender’ status under Johnson.

The Court leaves for its summer recess after today, resuming in October. A briefing and oral argument schedule will be set for the fall. A decision will probably be handed down early in 2017.

Beckles v. United States, Case No. 15-8544 (certiorari granted, June 27, 2016)

MATHIS SAYS IT DOES NOT REALLY MATTER WHAT YOU DID

Everyone knows the Supreme Court handed down a decision last week in Mathis v. United States that further gutted the “burglary” element under the Armed Career Criminal Act. But what does Mathis mean?

Under the ACCA, two kinds of crimes count as “violent” priors that trigger the minimum 15-year sentence: the enumerated crimes clause (which identifies by name the offenses of burglary, extortion, arson, or use of explosives); and the force clause (crimes with use or threatened use of violence causing physical harm). For a state offense – such as burglary – to count under the enumerated crimes clause, it must contain elements no broader than the elements of the common law version of the offense.

At common law, a burglary is defined as entering a building or other structure without authorization for the purpose of committing a felony. If a state burglary statute, for example, said that entering a building without authorization for the purpose of committing a felony was a burglary, but defined building to include car, boat or airplane, it was broader than the ACCA version of burglary.

At common law, a burglary is defined as entering a building or other structure without authorization for the purpose of committing a felony. If a state burglary statute, for example, said that entering a building without authorization for the purpose of committing a felony was a burglary, but defined building to include car, boat or airplane, it was broader than the ACCA version of burglary.

Richard Mathis has a passel of Iowa 3rd degree burglary convictions. An element of the offense is unauthorized entry into an “occupied structure.” So far, the statute sounds even narrower than the ACCA, meaning it should count toward Richard’s 15-year sentence. But elsewhere in the Iowa Code, an “occupied structure” was defined pretty broadly as “any building, structure, or land, water, or air vehicle.”

The 8th Circuit had ruled that the definition provided alternative elements of the offense, and because the elements were in the alternative, the statute was “divisible.” Therefore, the trial court was allowed to employ something the courts call “the modified categorical approach,” a fancy way of saying it could look at the state court record to find out exactly what Richard had done. It turned out he had burgled a house, which fits squarely within the common law definition of burglary, making the prior burglary a crime of violence.

Last week, the Supreme Court disagreed. It held that the “locations are not alternative elements, going toward the creation of separate crimes. To the contrary, they lay out alternative ways of satisfying a single locational element… A jury need not agree on which of the locations was actually involved. In short, the statute defines one crime, with one set of elements, broader than generic burglary—while specifying multiple means of fulfilling its locational element, some but not all of which (i.e., buildings and other structures, but not vehicles) satisfy the generic definition.”

The Supreme Court said a court must ask only “whether the defendant had been convicted of crimes falling within certain categories” and not about “what the defendant had actually done.” Richard had been convicted of an Iowa offense that could have been committed by stealing a radio out of a car, a barf bag out of an airplane, or a life vest from a boat. The fact that he ripped off someone’s house did not matter. It’s what he could have done to violate the statute that mattered.

The Supreme Court said a court must ask only “whether the defendant had been convicted of crimes falling within certain categories” and not about “what the defendant had actually done.” Richard had been convicted of an Iowa offense that could have been committed by stealing a radio out of a car, a barf bag out of an airplane, or a life vest from a boat. The fact that he ripped off someone’s house did not matter. It’s what he could have done to violate the statute that mattered.

Justice Alito, dissenting, argued that “the upshot of today’s decision is that all burglary convictions in a great many States may be disqualified from counting as predicate offenses under ACCA.”

Mathis v. United States, Case No. 15–6092 (Supreme Court, June 23, 2016)

BACK TO SCHOOL TIME

The U.S. Dept. of Education has chosen 67 two-year and four-year colleges for a pilot program that will offer Pell Grants to inmates. The program – called Second Chance Pell – will enroll 12,000 prisoners at more than 100 federal and state correctional institutions across the country, aimed at prisoners likely to be released within the next five years.

The U.S. Dept. of Education has chosen 67 two-year and four-year colleges for a pilot program that will offer Pell Grants to inmates. The program – called Second Chance Pell – will enroll 12,000 prisoners at more than 100 federal and state correctional institutions across the country, aimed at prisoners likely to be released within the next five years.

In some locations, the program will begin as early as next week. Most of the colleges chosen will offer classes in person at the correctional facilities, while some will offer online classes.

Most prisoners have been ineligible for Pell Grants since Congress banned the aid in 1994. “That ban remains in place until Congress acts,” the Secretary of Education said last week. “We are using our experimental authority under the Higher Education Act to support this pilot.”

Studies show that for every dollar spent on college course for inmates, the government saves $4-5 in incarceration costs.

Inside Higher Ed, Prisoners to Get ‘Second Chance Pell’ (June 24, 2016)

HAVE YOU STOPPED BEATING YOUR WIFE YET?

Stephen Voisine pled guilty in state court to a misdemeanor assault on his wife. Several years later, he was charged with a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), because a conviction for a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. The state statute provides that one can violate it intentionally or recklessly. Steve argued that 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) requires that the use of force needed for the offense to qualify as one that forfeits the right to possess guns must be intentional, not just reckless.

Today, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts, holding that a reckless domestic assault qualifies as a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. The Court said that nothing in the phrase “use. . . of physical force” indicates that § 922(g)(9) distinguishes between domestic assaults committed knowingly or intentionally and those committed recklessly. “Dictionaries consistently define the word “use” to mean the “act of employing” something. Accordingly, the force involved in a qualifying assault must be volitional; an involuntary motion, even a powerful one, is not naturally described as an active employment of force. But nothing about the definition of “use” demands that the person applying force have the purpose or practical certainty that it will cause harm, as compared with the understanding that it is substantially likely to do so.”

Today, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts, holding that a reckless domestic assault qualifies as a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. The Court said that nothing in the phrase “use. . . of physical force” indicates that § 922(g)(9) distinguishes between domestic assaults committed knowingly or intentionally and those committed recklessly. “Dictionaries consistently define the word “use” to mean the “act of employing” something. Accordingly, the force involved in a qualifying assault must be volitional; an involuntary motion, even a powerful one, is not naturally described as an active employment of force. But nothing about the definition of “use” demands that the person applying force have the purpose or practical certainty that it will cause harm, as compared with the understanding that it is substantially likely to do so.”

The Court concluded that reckless conduct, “which requires the conscious disregard of a known risk, is not an accident: It involves a deliberate decision to endanger another. The relevant text thus supports prohibiting petitioners, and others with similar criminal records, from possessing firearms.”

Voisine v. United States, Case No. 14-10154 (Supreme Court, June 27, 2016)

HIGH LIVIN’ IN THE OLD DOMINION

HIGH LIVIN’ IN THE OLD DOMINION

Former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell had a lousy marriage but a sweet deal. While running the state, the government alleged, Bob performed multiple “official acts” as governor in return for money, loans, expensive gifts and outings from Virginia businessman Jonnie R. Williams — who, prosecutors said, did all of those favors for the Guv in return for the his help in arranging state government contacts who could advance Williams’s business, the sale of a health supplement made from tobacco leaves.

Former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell had a lousy marriage but a sweet deal. While running the state, the government alleged, Bob performed multiple “official acts” as governor in return for money, loans, expensive gifts and outings from Virginia businessman Jonnie R. Williams — who, prosecutors said, did all of those favors for the Guv in return for the his help in arranging state government contacts who could advance Williams’s business, the sale of a health supplement made from tobacco leaves.

The trial was pretty seamy, exposing a dysfunctional marriage between a power couple who seemed to enrich themselves through wielding their power. Sounds kind of like the Clintons, doesn’t it? The issue, however, before the Supreme Court was whether making a few phone calls and opening doors for Gentleman Jonnie to meet with state officials constituted “official acts” or merely acceptable back-scratching.

The Court held that given its interpretation of “official act,” the District Court’s jury instructions were erroneous, and the jury may have con- victed Governor McDonnell for conduct that is not unlawful. “Because the errors in the jury instructions are not harmless beyond a reason- able doubt, the Court vacates Governor McDonnell’s convictions.”

Today, the Supreme Court vacated the Governor’s conviction. It held that an “official act” is a decision or action on a “question, matter, cause, suit, proceeding or controversy.” That question or matter must involve a formal exercise of governmental power, and must also be something specific and focused that is “pending” or “may by law be brought” before a public official. To qualify as an “official act,” the public official must make a decision or take an action on that ques- tion or matter, or agree to do so. Setting up a meeting, talking to another official, or organizing an event—without more—does not fit that definition of “official act.”

McDonnell v. United States, Case No. 15-474 (Supreme Court, June 27, 2016).

SOB STORY

Ralph Dennis was no rocket scientist. He sported an IQ of 74 and a taste for bud and coke. Besides drug dealing, his biggest mistake was to be friends with Kevin Burk.

Kevin was an ex-felon with a taste for guns. When he was caught with one, he volunteered to help the ATF rather than go back to prison. Agents asked him for names of violent criminals, and Kevin gave up Ralph as a guy who did home invasions.

So ATF concocted a reverse sting, telling Kevin to recruit Ralph to help him rob a stash house. Ralph was not enthusiastic. In fact, he turned Kevin down three times before agreeing to help, and then only because Kevin sold Ralph the sob story that he needed money to help pay for his mom’s cancer treatments.

So ATF concocted a reverse sting, telling Kevin to recruit Ralph to help him rob a stash house. Ralph was not enthusiastic. In fact, he turned Kevin down three times before agreeing to help, and then only because Kevin sold Ralph the sob story that he needed money to help pay for his mom’s cancer treatments.

The ATF wanted Ralph to bring guns to the party, but Ralph didn’t have any. He wanted to use stun guns on the stash house guards so no one got hurt. So Kevin provided Ralph with a gun, which he had when the ATF busted him.

At trial, Ralph’s lawyer asked for an entrapment instruction. The district court refused, saying that Ralph’s prior crimes proved he was predisposed to join the robbery scheme, and he could have withdrawn but he did not.

Last week, the 3rd Circuit granted Ralph a new trial, holding the jury should have been given an entrapment instruction. The appeals panel cited Kevin’s central role in recruiting, coaching and equipping Ralph, noting that “Burk’s plea affected Dennis’ decision to join the scheme. And this is unsurprising—a friend whom he had known for years asked for help to pay for his mother’s cancer treatment…. Indeed, the entirety of Burk and Dennis’ conversation seems predicated on friendship.”

Last week, the 3rd Circuit granted Ralph a new trial, holding the jury should have been given an entrapment instruction. The appeals panel cited Kevin’s central role in recruiting, coaching and equipping Ralph, noting that “Burk’s plea affected Dennis’ decision to join the scheme. And this is unsurprising—a friend whom he had known for years asked for help to pay for his mother’s cancer treatment…. Indeed, the entirety of Burk and Dennis’ conversation seems predicated on friendship.”

The district court found Ralph’s evidence on whether he was predisposed to commit the crime was equivocal because while his three refusals might suggest he was not predisposed, they also showed he could say ‘no’ to Kevin when he wanted to. The Court of Appeals found, however, that “it was not for the District Court to decide the evidence ‘cut both ways’ and draw a conclusion against Dennis. Similarly, it was impermissible for the Court to credit the Government’s evidence when Dennis presented evidence to the contrary.”

Weighing evidence and drawing inferences is a job for the jury, the 3rd Circuit said, not the judge. There was enough evidence to justify the entrapment instruction, and Ralph was thus entitled to a new trial.

United States v. Dennis, Case No. 14-3561 (3rd Circuit, June 24, 2016)

SENTENCING REFORM BILL WOULD AUTHORIZE ASSIGNING ‘RISK SCORES’ TO INMATES

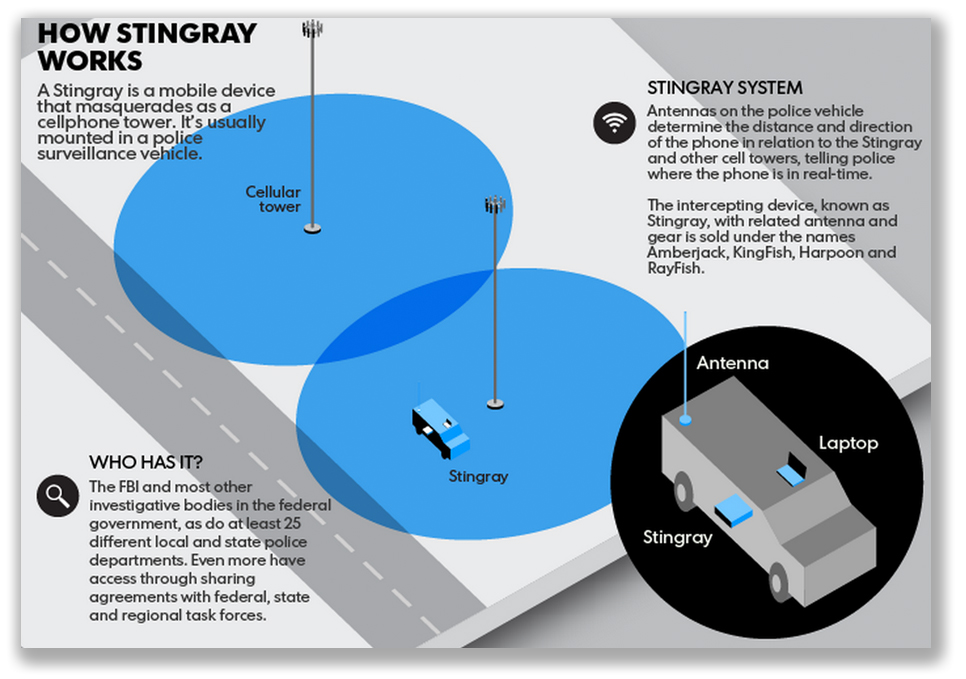

One aspect of the pending sentencing reform bill attracted some critical attention last week: Truthout, a progressive website, reported on a Pro Publica study of the Act’s provision that would require the government to rate federal prisoners’ risk of committing a future crime and treat them differently according to those ratings. The measure directs the Attorney General to develop a new formula for predicting future behavior or adopt an existing tool. The BOP would then use the algorithm to score and classify inmates.

One aspect of the pending sentencing reform bill attracted some critical attention last week: Truthout, a progressive website, reported on a Pro Publica study of the Act’s provision that would require the government to rate federal prisoners’ risk of committing a future crime and treat them differently according to those ratings. The measure directs the Attorney General to develop a new formula for predicting future behavior or adopt an existing tool. The BOP would then use the algorithm to score and classify inmates.

Inmates who receive low “risk scores” – and those who manage to lower their scores over time – would be allowed to shave time off of their sentences with credits earned through rehabilitation and education programs. “High risk” inmates would not be eligible for sentence reduction.

Such tests are increasingly popular around the country, Truthout complained, used to make decisions about everything from bail to sentencing. The scores are meant as a counterweight to the vagaries and biases of human decisions.

Yet the formulas are often not transparent. ProPublica recently investigated one popular tool sold by a for-profit company and found that it’s frequently wrong and is biased against blacks.

According to an analysis by Federal Public & Community Defenders, the risk scoring system “described in the bill is novel and untested.” The report argues that the scoring of prisoners would be a problem because factors that go into risk assessment calculations tend to correlate with socioeconomic class and race. A fairer and more effective approach, the group says, would be to make recidivism-reduction programs available to all inmates equally.

Truthout, The Senate’s Popular Sentencing Reform Bill Would Sort Prisoners by Risk Score (June 24, 2016)

FORMER AUSA WRITES CONFESSIONAL

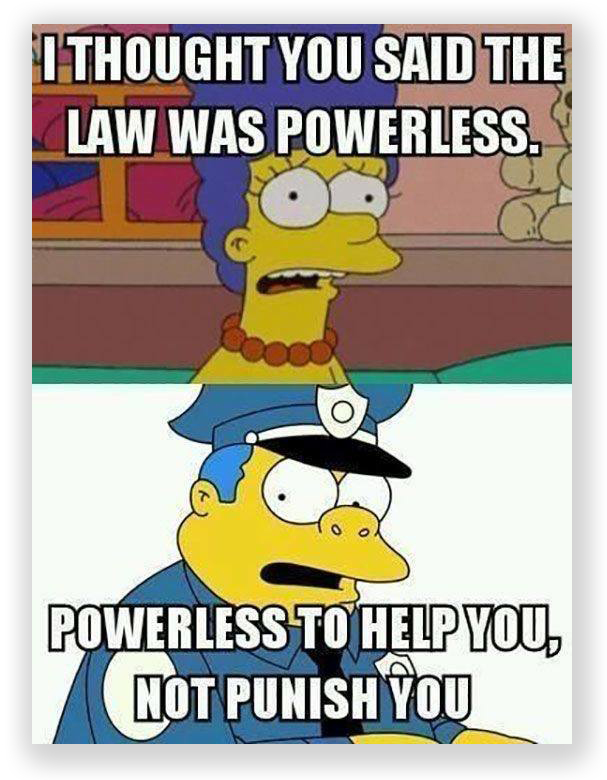

A former Assistant United States Attorney turned defense attorney wrote a long and candid article last week discussing the mindset of federal prosecutors. The piece included a discussion about how AUSAs approach the violation of a defendant’s constitutional rights.

Prosecutors are encouraged to argue that rights are irrelevant, White said. “The argument goes by genteel names like ‘harmless error’ and ‘lack of prejudice’ and ‘immaterial,’ and it is omnipresent in modern criminal procedure. As a prosecutor, it was my job on dozens of occasions to invoke those doctrines to assert that even if defendants’ rights were violated, those violations didn’t matter.”

Prosecutors are encouraged to argue that rights are irrelevant, White said. “The argument goes by genteel names like ‘harmless error’ and ‘lack of prejudice’ and ‘immaterial,’ and it is omnipresent in modern criminal procedure. As a prosecutor, it was my job on dozens of occasions to invoke those doctrines to assert that even if defendants’ rights were violated, those violations didn’t matter.”

As an example, White said, “the 4th Amendment requires police to get a search warrant before they make forcible entry to your home to search it. May police officers lie to a magistrate to get that warrant, or deliberately omit information that contradicts the evidence they offer? No, says the Supreme Court – that would violate your rights. But the violation only has a remedy if the lie is material – that is, if the warrant application, stripped of the lie or supplemented with the deceitfully omitted information, would no longer be enough to support probable cause. So when a defendant discovers that law enforcement agents have lied to get a warrant, a prosecutor has every incentive to argue that the lie didn’t matter…”

“The prosecutor will be making this argument in the context of a search that did turn up incriminating evidence,” White wrote, “which tends to bias judges towards upholding searches. After all… wasn’t the cop’s suspicion proved right? Probable cause is a very relaxed and inherently subjective standard, requiring only a “fair probability” that evidence will be found. The practical effect is that law enforcement can lie in warrant applications with relative impunity, and it’s a prosecutorial duty to think of ways to explain how those lies are irrelevant.”

“The prosecutor will be making this argument in the context of a search that did turn up incriminating evidence,” White wrote, “which tends to bias judges towards upholding searches. After all… wasn’t the cop’s suspicion proved right? Probable cause is a very relaxed and inherently subjective standard, requiring only a “fair probability” that evidence will be found. The practical effect is that law enforcement can lie in warrant applications with relative impunity, and it’s a prosecutorial duty to think of ways to explain how those lies are irrelevant.”

The deal is different if the defendant lies… “If federal agents lie about you to a magistrate to get a search warrant, the question is whether the lie did actually make a difference. But if you lie to federal agents, the standard is far less forgiving… Thus prosecutors are trained to treat defendants’ wrongdoing harshly and government wrongdoing leniently.”

Reason, Confessions of an Ex-Prosecutor (June 23, 2016)

SENTENCING REFORM – EVEN FAMM IS GIVING UP?

Anyone who does not think the news cycle drives Congress probably holds title to the Brooklyn Bridge. Last week, the shootings in Orlando dominated the news, and Congress was mired in hastily written bills that would have banned assault rifles – used in fewer than 3% of murders  – and kept people on the government’s “no-fly” list from buying guns. Democrats staged a “sit in” on the floor of the House because they were not getting their way. There was no sentence reform talk on Capitol Hill. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 continues to languish in the Senate (S. 2123) and the House (H.R. 3713).

– and kept people on the government’s “no-fly” list from buying guns. Democrats staged a “sit in” on the floor of the House because they were not getting their way. There was no sentence reform talk on Capitol Hill. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 continues to languish in the Senate (S. 2123) and the House (H.R. 3713).

It hardly matters that the legislation enjoys bipartisan support. Last week, Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) wrote in the Dallas Morning News that “locking people up and throwing away the key, as it turns out, is not always the most effective way to stop crime. It is also an expensive and inefficient way to spend taxpayer dollars.” Citing Texas’s dramatic decrease in prison populations, Sen. Cornyn argued, “the Texas model is worth bringing to the rest of the country. Now Congress has that chance. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act is a bipartisan bill that incorporates many of these policies that have proven effective in conservative states – our laboratories of democracy. Importantly, this legislation will also help restore a key part of our criminal justice system that is too often forgotten: rehabilitation. Through education, job training and faith-based programs, low-level inmates will learn valuable life skills that they can take back home to their communities, helping them become productive members of society.”

But enough happy talk. Although the year is only half over according to the calendar, Congress is already winding down. The Senate only has 55 more work days this year (that’s a total of 11 work weeks out of the remaining 27 weeks in the year). The House only has 42 days left. A new Congress starts in January, meaning that any bill still pending at the end of the year will disappear, and the process must start over in 2017. That’s very little time to get sentencing reform passed.

In a puff story last week on Kevin Ring, former lobbyist and Federal inmate, now vice president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, The Hill referred to sentencing reform legislation as “once the political darling of a divided Senate and now an apparent victim of the rapidly shrinking 2016 congressional calendar… With the November election looming — and all the incendiary rhetoric that has colored this year’s contest — FAMM is happy to wait until 2017 for wholesale reforms, Ring says. The group had formerly supported a bipartisan effort from the Senate Judiciary Committee, but now he fears being forced to fight back a myriad of tough-on-crime amendments put forward by jumpy lawmakers if the bill were to reach the floor.

In a puff story last week on Kevin Ring, former lobbyist and Federal inmate, now vice president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, The Hill referred to sentencing reform legislation as “once the political darling of a divided Senate and now an apparent victim of the rapidly shrinking 2016 congressional calendar… With the November election looming — and all the incendiary rhetoric that has colored this year’s contest — FAMM is happy to wait until 2017 for wholesale reforms, Ring says. The group had formerly supported a bipartisan effort from the Senate Judiciary Committee, but now he fears being forced to fight back a myriad of tough-on-crime amendments put forward by jumpy lawmakers if the bill were to reach the floor.

“We think the window is, if not closed, close to closing,” The Hill quoted Ring as saying. “But in our view, this isn’t the best time to be passing criminal justice reform anyway. In a presidential election year, you’re beating back really bad political ideas. The worst mandatory minimums are passed during election years because they are seen as politically valuable.”

Legal Information Services Associates provides research and drafting services to lawyers and inmates. With over 20 years experience in post-conviction motions and sentence modification strategy, we provide services on everything from direct appeals to habeas corpus to sentence reduction motions to halfway house and home confinement placement. If we can help you, we’ll tell you that. If what you want to do is futile, we’ll tell you that, too.

If you have a question, contact us using our handy contact page. We don’t charge for initial consultation.

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) said last Friday that the House will consider a package of six criminal justice reform bills – including the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 (H.R. 3713) in September.

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) said last Friday that the House will consider a package of six criminal justice reform bills – including the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 (H.R. 3713) in September.