Vol. 2, No. 9

This week:

Innocence is not Irrelevant

A Break-Even Week For Amendment 782 Motions

Judge Blasts Guidelines

Where You Are Really Matters on Rule 35

Nothing New About Descamps: 8th Circuit Denies Retroactivity

Quiet Week For Sentencing Reform

INNOCENCE IS NOT IRRELEVANT

A 1979 law review essay criticizing habeas corpus practice in America was famously entitled Is Innocence Irrelevant? Collateral Attacks on Criminal Judgments. Last week, the 4th Circuit answered that question, insofar as waivers are concerned.

Richard Adams found convenience stores to be convenient places to get money. Using a gun, he robbed a string of them. He was charged with eight counts, including being a felon in possession of a gun in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) (“F-I-P”), due to some prior North Carolina drug trafficking convic-tions. Like most defendants, he signed a plea agreement in which he waived the right to file any appeal or Sec. 2255 motion.

Richard Adams found convenience stores to be convenient places to get money. Using a gun, he robbed a string of them. He was charged with eight counts, including being a felon in possession of a gun in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g) (“F-I-P”), due to some prior North Carolina drug trafficking convic-tions. Like most defendants, he signed a plea agreement in which he waived the right to file any appeal or Sec. 2255 motion.

A few years later, the 4th Circuit handed down United States v. Simmons, holding that a lot of hybrid North Carolina drug convictions that had looked like felonies were really misdemeanors. All of a sudden, Richie’s prior felonies were no longer felonies, meaning that he was actually innocent of being a felon-in-possession. He filed a Sec. 2255 motion, asking that that one conviction be vacated. The Government argued that his waiver meant that he could not do anything about the F-I-P count.

Last week, the 4th Circuit said Richie’s waiver did not keep him from showing he was innocent. The Court said, “We will refuse to enforce an otherwise valid waiver if to do so would result in a miscarriage of justice. A proper showing of ‘actual innocence’ is sufficient to satisfy the ‘miscarriage of justice’ requirement. Such a showing renders the claim outside the scope of the waiver.”

The district court had complained that Adams could not show he was prejudiced by the F-I-P conviction, because without it, the court would have given him the same sentence. The Court of Appeals didn’t think much of this reasoning, noting that “the government wisely does not press this argument on appeal. Felony convictions carry a myriad of collateral consequences above and beyond time in prison, including the possibility that a future sentence will be enhanced based on the challenged conviction, the possibility of using the conviction for future impeachment, and societal stigma. Because an erroneous conviction and accompanying sentence, even a concurrent sentence, can have significant collateral consequences, the fact that Adams’s sentence would not change does not bar his claim.”

United States v. Adams, Case No. 13-7107 (4th Cir. Feb. 19, 2016)

A BREAK-EVEN WEEK FOR AMENDMENT 782 MOTIONS

Two Court of Appeals decisions last week on Sec. 3582(c)(2) motions split the ticket for defendants.

When the dust settled in 1998, Charles Robinson was convicted of three drug-trafficking counts, with a Guidelines range of life. The court couldn’t give him life on the counts of conviction, so it did what it could – sentencing him to the max of 40 years on two of the counts, and the max of 20 years on the other, all consecutive to each other. It was 100 years – as close to life as the judge could get.

When the dust settled in 1998, Charles Robinson was convicted of three drug-trafficking counts, with a Guidelines range of life. The court couldn’t give him life on the counts of conviction, so it did what it could – sentencing him to the max of 40 years on two of the counts, and the max of 20 years on the other, all consecutive to each other. It was 100 years – as close to life as the judge could get.

Thirteen years later Amendment 782 to the Guidelines retroactively reduced the base offense level for Charles’ crimes from 43 to 42. The effect was to change the recommended guidelines sentence from life to 30 years to life. When Charles filed for a sentence reduction, the judge reduced his sentence, but thought he had to keep the sentences consecutive. So Charles got 30 years on each of two counts, and kept 20 years on the third – with all three sentences still running wild – for an 80-year sentence.

Last week, the 7th Circuit reversed. It explained that when Charles was sentenced, “his recommended guideline sentence was longer (life, as we said) than the maximum permissible sentence on any one count. The judge thus had to make the sentences on the individual counts consecutive in order to get as close to a life sentence as he could. As a result of Amendment 782, however, the low end of the defendant’s guidelines range — 30 years — dropped below the statutory maximum for any single count (40 years), and if a judge wants to sentence a defendant at the bottom of the new guidelines range he can do so by imposing sentences not exceeding 30 years on each count and making all the sentences run concurrently, as authorized by U.S.S.G. § 5G1.2(c) – 80 years is not the floor.”

Last week, the 7th Circuit reversed. It explained that when Charles was sentenced, “his recommended guideline sentence was longer (life, as we said) than the maximum permissible sentence on any one count. The judge thus had to make the sentences on the individual counts consecutive in order to get as close to a life sentence as he could. As a result of Amendment 782, however, the low end of the defendant’s guidelines range — 30 years — dropped below the statutory maximum for any single count (40 years), and if a judge wants to sentence a defendant at the bottom of the new guidelines range he can do so by imposing sentences not exceeding 30 years on each count and making all the sentences run concurrently, as authorized by U.S.S.G. § 5G1.2(c) – 80 years is not the floor.”

Things didn’t work out as well for Eric Smith in the 6th Circuit. When he was sentenced in 1994, he qualified as a career offender under Guidelines Sec. 4B1.1. However, his Guidelines level under the drug-quantity table was higher, so the court applied Sec. 2D1.1, and gave him 30 years.

Eric applied for a reduction under Amendment 782, but last week, the 6th Circuit shot him down. Noting that the career-offender offense level applies only when it is greater than the otherwise applicable offense level, the Court did the math. “Smith’s career-offender offense level – both at his sentencing and under current law – is 37. If Amendment 782 had been in effect at Smith’s sentencing, his drug-trafficking offense level would have been 34, which produces a Guidelines range of 262 to 327 months when combined with Smith’s criminal history category. Because 37 is greater than 34, the district court would have applied the career-offender offense level if Amendment 782 had been in effect at Smith’s sentencing. An offense level of 37 combined with Smith’s criminal history category of VI produces the same Guidelines range that the district court applied at Smith’s sentencing: 360 months to life.”

United States v. Robinson, Case No. 15‐2091 (7th Cir. Feb. 22, 2016)

United States v. Smith, Case No. 15-5853 (6th Cir. Feb. 25, 2016)

JUDGE BLASTS GUIDELINES

“So much of sentencing discretion is vested now in the U.S. Attorney’s Office,” Senior U.S. District Judge John Coughenour (W.D. Washington) said in a magazine article last week. “By their charging decisions, they can tie the hands of the sentencing judge, particularly on mandatory minimums. And [prosecutors’] discretion, by the way, is exercised in darkness.” By that, he suggests that prosecutors can charge defendants under any statute they choose, and their charging decisions are unreviewable.

“So much of sentencing discretion is vested now in the U.S. Attorney’s Office,” Senior U.S. District Judge John Coughenour (W.D. Washington) said in a magazine article last week. “By their charging decisions, they can tie the hands of the sentencing judge, particularly on mandatory minimums. And [prosecutors’] discretion, by the way, is exercised in darkness.” By that, he suggests that prosecutors can charge defendants under any statute they choose, and their charging decisions are unreviewable.

If that statute carries a hefty minimum sentence, the judge cannot lighten the punishment. “What we do,” Judge Coughenour said, referring to judges, “we do out in the sunlight, and we have to be subject to appellate review. We have to explain ourselves. We have to endure press reaction to what we do.” Nobody reviews the U.S. attorney’s decisions. “In fact,” says Coughenour, “we are precluded from reviewing those charging decisions. And here you have people who are put on the bench by the president of the United States and confirmed by the United States Senate—presumably for their judgment. I mean, that’s why they call it ‘judging’.”

A former AUSA, Mark Osler – a law professor who worked as a prosecutor in Detroit in the 1990s – agreed: “The whole structure is still guidelines-focused … That baseline seems so objective. It’s a number, and there’s this presumptive objectivity when you’re looking at something that says, ‘121 months.’ Because it’s so specific, it has this veneer of science around it. Where, in reality, it’s pretty much just made up.”

Van Meter, “One Judge Makes the Case for Judgment,” The Atlantic (Feb. 25, 2016)

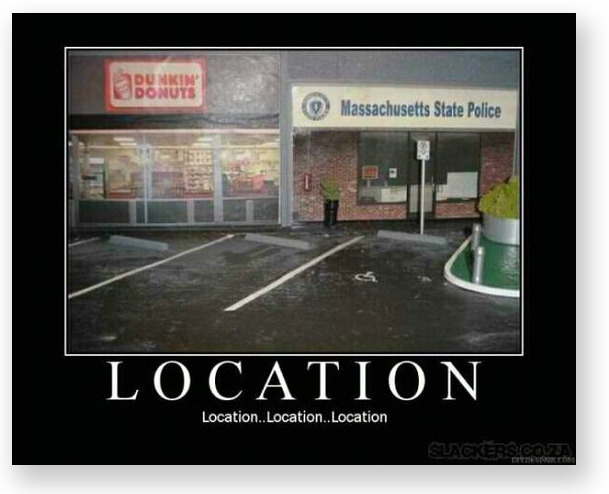

WHERE YOU ARE REALLY MATTERS ON RULE 35

Everyone knows that the three most important factors in real estate are location, location, location. It turns out the same is true for defendants wanting to get Rule 35 sentence reductions.

The Government uses two mechanisms to reward cooperating defendants. They can either get a reduction at sentencing for substantial cooperation, a Government motion under U.S.S.G. Sec. 5K1.1, or – if the assistance comes later or is not complete by sentencing – they get resentenced to less time when the Government makes a motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b).

The Government uses two mechanisms to reward cooperating defendants. They can either get a reduction at sentencing for substantial cooperation, a Government motion under U.S.S.G. Sec. 5K1.1, or – if the assistance comes later or is not complete by sentencing – they get resentenced to less time when the Government makes a motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b).

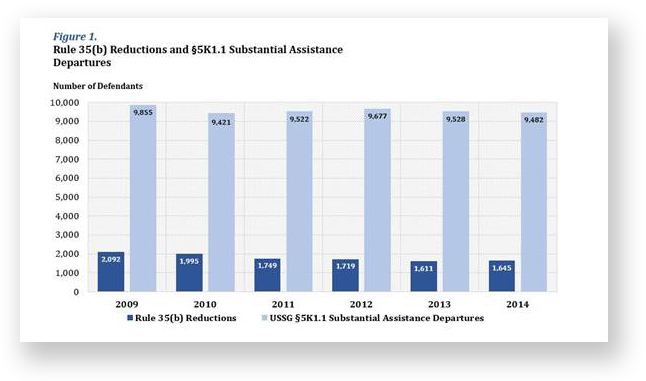

Last week, the United States Sentencing Commission released a 42-page study of the use of Rule 35(b) motions. The report, which reviewed nearly 11,000 Rule 35(b) reductions over the last six years, found that

• Rule 35(b) sentencing reductions are used relatively rarely, although a few districts use them often.

• Most defendants receiving a Rule 35(b) reduction were originally sentenced within their guideline ranges. This suggests that courts rarely depart or vary for reasons other than substantial assistance with this group of defendants.

• Most defendants receiving a Rule 35(b) reduction were convicted of a drug trafficking offense with a mandatory minimum sentence.

• Rule 35(b) reductions generally provide less benefit than do Sec. 5K1.1 substantial assistance departures. This is true whether the Rule 35(b) sentencing reduction is compared to the 5K1.1 substantial assistance departure in terms of the ultimate sentence length or by the percentage extent of the reduction from the original sentence.

• Rule 35(b) reductions generally provide less benefit than do Sec. 5K1.1 substantial assistance departures. This is true whether the Rule 35(b) sentencing reduction is compared to the 5K1.1 substantial assistance departure in terms of the ultimate sentence length or by the percentage extent of the reduction from the original sentence.

• Rule 35(b) sentencing reductions are usually less beneficial than 5K1.1 departures, but defendants who get both a 5K1.1 departure and a Rule 35(b) reduction enjoy the largest overall reduction in their sentences, regardless of how that reduction is measured.

• Defendants sentenced in jurisdictions that primarily use Rule 35(b) reductions overall receive less benefit for their substantial assistance than do those in jurisdictions that rely primarily on 5K1.1 departures or a combination of Rule 35(b) reductions and 5K1.1 departures.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, The Use of Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b) (February, 2016)

NOTHING NEW ABOUT DESCAMPS: 8TH CIRCUIT DENIES RETROACTIVITY

In 2005, a jury convicted Will Head-bird of being a felon-in-possession, and applied the Armed Career Criminal Act because of his prior felonies. Headbird was sentenced to 327 months in prison. Nine years later, Headbird argued that the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Descamps v. United States meant that his prior convictions were not violent, and that his sentence should be cut to 10 years.

In 2005, a jury convicted Will Head-bird of being a felon-in-possession, and applied the Armed Career Criminal Act because of his prior felonies. Headbird was sentenced to 327 months in prison. Nine years later, Headbird argued that the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Descamps v. United States meant that his prior convictions were not violent, and that his sentence should be cut to 10 years.

Last week, the 8th Circuit declared Headbird’s motion was too late, because Descamps did not create a newly recognized right that applied retroactively to 28 U.S.C. Sec. 2255 cases.

Sec. 2255(f)(3) gives inmates one year to file a 2255 after the Supreme Court decides a case announcing “new rule” that “breaks new ground or imposes a new obligation on the states or the federal government.” A case like Descamps announces a new rule if the “result was not dictated by precedent,” that is, if the case’s outcome would not have been “apparent to all reasonable jurists.” Rules that just apply an existing principle to a new set of facts typically do not constitute new rules.

The 8th Circuit found that Descamps just applied existing general principles governing the categorical and modified categorical approaches to indivisible statutes. The Supreme Court said its Descamps opinion was “all but” resolved by prior decisions. Thus, the 8th Circuit said, Headbird’s motion does not rely on a right that was “newly recognized” by the Supreme Court, and was much too late.

United States v. Headbird, Case No. 15-1468 (8th Cir. Feb. 19, 2016)

SENTENCING REFORM STALLED FOR NOW

Hardly anything happened on Capitol Hill last week to advance the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015, now before the Senate in S. 2123, and before the House in H.R. 3713. H.R. 3713 picked up three more cosponsors, Democrats from Ohio, Michigan and Colorado. The Senate bill now has 28 cosponsors, while the House measure has 56.

Debate continued unabated in the press, however. An article in the Wall Street Journal last week by a criminal law professor argued that “relatively few prisoners today are locked up for drug offenses.” Of state prisoners, only “about 16%, or 208,000 people, are incarcerated for drug crimes. Of those, less than a quarter were in for mere possession … Critics of “mass incarceration” often point to the federal prisons, where half of inmates, or about 96,000 people, are drug offenders. But 99.5% of them are traffickers. The notion that prisons are filled with young pot smokers, harmless victims of aggressive prosecution, is patently false.”

Debate continued unabated in the press, however. An article in the Wall Street Journal last week by a criminal law professor argued that “relatively few prisoners today are locked up for drug offenses.” Of state prisoners, only “about 16%, or 208,000 people, are incarcerated for drug crimes. Of those, less than a quarter were in for mere possession … Critics of “mass incarceration” often point to the federal prisons, where half of inmates, or about 96,000 people, are drug offenders. But 99.5% of them are traffickers. The notion that prisons are filled with young pot smokers, harmless victims of aggressive prosecution, is patently false.”

The New York Times, however, published a letter last Wednesday from the presidents of the African American Mayors Asso-ciation and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, calling for “Congress to stop dragging its feet” on passing sentencing reform. The day before, the Salt Lake Tribune ran an op-ed article supporting sentence reform. And last Friday, the Lincoln, Nebraska, Journal Star demanded that Congress fix “ridiculous sentences.”

The New York Times, however, published a letter last Wednesday from the presidents of the African American Mayors Asso-ciation and the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, calling for “Congress to stop dragging its feet” on passing sentencing reform. The day before, the Salt Lake Tribune ran an op-ed article supporting sentence reform. And last Friday, the Lincoln, Nebraska, Journal Star demanded that Congress fix “ridiculous sentences.”

The Journal-Star editorial was sparked by a remarkable sentencing Feb. 12 in Lincoln federal court. U.S. District Judge John Gerrard roundly criticized the 10-year sentence he was giving to a nonviolent, recovering meth user. “The only reason I’m imposing the sentence that I am imposing today is because I have to,” he told the defendant. “That’s what Congress mandates.” The judge called the defendant “Exhibit A for why Congress should pass the Smart on Crime Act.” Last June, in a similar case, he called another defendant the poster child for it. In both of the cases, Judge Gerrard – a former Nebraska Supreme Court justice – said the sentence didn’t fit the crime. “There should be imprisonment,” he said, “but 10 years in cases like these is ridiculous, draconian even.”

The Journal-Star editorial was sparked by a remarkable sentencing Feb. 12 in Lincoln federal court. U.S. District Judge John Gerrard roundly criticized the 10-year sentence he was giving to a nonviolent, recovering meth user. “The only reason I’m imposing the sentence that I am imposing today is because I have to,” he told the defendant. “That’s what Congress mandates.” The judge called the defendant “Exhibit A for why Congress should pass the Smart on Crime Act.” Last June, in a similar case, he called another defendant the poster child for it. In both of the cases, Judge Gerrard – a former Nebraska Supreme Court justice – said the sentence didn’t fit the crime. “There should be imprisonment,” he said, “but 10 years in cases like these is ridiculous, draconian even.”

Legal Information Services Associates provides research and drafting services to lawyers and inmates. With over 20 years experience in post-conviction motions and sentence modification strategy, we provide services on everything from direct appeals to habeas corpus to sentence reduction motions to halfway house and home confinement placement. If we can help you, we’ll tell you that. If what you want to do is futile, we’ll tell you that, too.

If you have a question, contact us using our handy contact page. We don’t charge for initial consultation.

Would you like a copy of this newsletter in PDF format? Click here.