We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

YOU SHOULD HAVE TOLD ME THAT

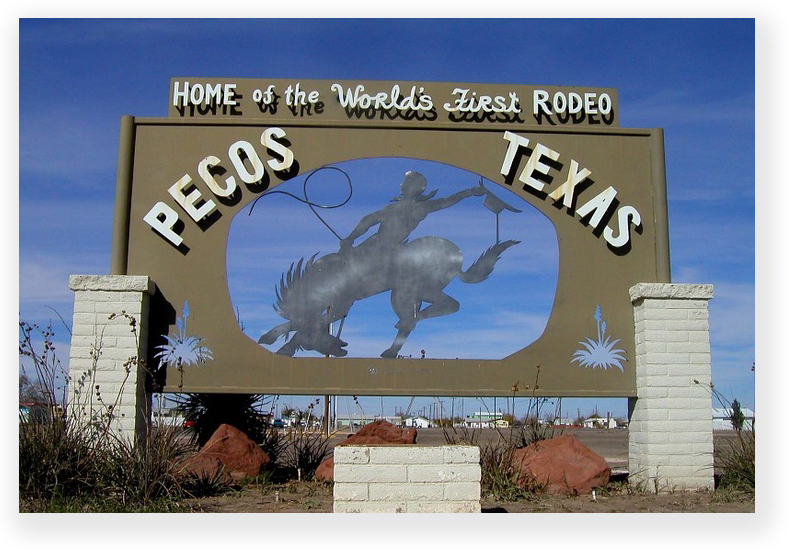

Mike DiFalco had a problem. He was charged with conspiracy and possession with intent to distribute over 50 grams of meth. That’s problem enough, but Mike’s was enormously bigger because this was not his first rodeo: he had been convicted of enough prior drug offenses to be facing a mandatory life sentence.

When Mike’s co-conspirator made a plea deal with the government, Mike could see the handwriting on the wall. So Mike did what any sensible defendant would have done. He made his own deal, agreeing to plead guilty in exchange for the prosecutor filing a notice under 21 U.S.C. Sec. 851 to only one prior. The effect of the deal was to lock in a mandatory minimum of 20 years instead of life.

A sure cure for insomnia is to wade through the dense verbiage of 21 U.S.C. Sec. 841(b), which specifies all sorts of different sentences for drug trafficking according to factors like drug quantity, whether anyone died, and number of prior drug offenses. In Mike’s case, his multiple priors were the driver of a mandatory life sentence, but his deal locked in a mandatory minimum of 20 years instead of life.

In order to get a higher mandatory minimum sentence applied to the defendant, the government is required by Sec. 851 to “file an information with the court… stating in writing the previous convictions to be relied upon… Clerical mistakes in the information may be amended at any time prior to the pronouncement of sentence.”

The government filed its 851 notice, but bolloxed up the facts pretty badly. The notice said Mike had been convicted in 2007 for sale of amphetamine and marijuana in Bartow County, Florida. But there was no 2007 conviction: rather, he had been convicted in 2002 of trafficking in amphetamine, manufacture of marijuana, possession of Ecstasy and Alprazolam, use or possession of drug paraphernalia, and driving with a suspended license in Polk County, Florida. He had a sheaf of other convictions for running a chop shop, weapons, and other drugs. Significantly, he had been convicted of nothing in 2007.

Mike’s plea deal included the customary waiver language, in which he agreed not to challenge the sentence on appeal except in limited cases (none of which applied). Nevertheless, he appealed his 20-year sentence on the grounds that the no one ever told him that he was waiving an appeal and that he faced a minimum of 20 years. For good measure, he argued as well that the 851 notice was defective.

Last Tuesday, the 11th Circuit – reciting all of the evidence in the record showing that Mike knew exactly what he had agreed to – shot him down. The appellate court’s decision is unremarkable in one regard, because contrary to the hopes of inmates that none of those provisions in plea agreements or questions and answers in front of the judge mean anything, appeal waivers are enforceable and when a defendant tells a judge he or she understands the plea agreement, the court’s going to hold the defendant to it.

Last Tuesday, the 11th Circuit – reciting all of the evidence in the record showing that Mike knew exactly what he had agreed to – shot him down. The appellate court’s decision is unremarkable in one regard, because contrary to the hopes of inmates that none of those provisions in plea agreements or questions and answers in front of the judge mean anything, appeal waivers are enforceable and when a defendant tells a judge he or she understands the plea agreement, the court’s going to hold the defendant to it.

The twist is that the 11th Circuit – like a number of other circuits – has previously held that Sec. 851 is a jurisdictional statute. That is, compliance with the requirements of Sec. 851 was a precondition to the district court even having the authority to impose the mandatory minimum sentence. Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, with no authority other than what Congress has given them. If Sec. 851 is a jurisdictional statute, and if the government did not comply with the literal wording of the statute, the court thus lacks subject-matter jurisdiction to impose the higher sentence.

Inmates filing post-conviction motions love “jurisdiction” arguments without really appreciating what the term means. They often make the most pedestrian statutory provision into a “jurisdictional” one. To Mike, the importance making Sec. 851 into a jurisdiction statute was clear: a party cannot waive a jurisdictional defect, and the failure to complain about such a defect earlier in a case is no bar to complaining about it later. In short, under 11th Circuit law that existed when Mike was sentenced, his waiver did not encompass a complaint that the government had breached Sec. 851.

Unfortunately for Mike, since the time the 11th Circuit and others had found Sec. 851 to be jurisdictional, the Supreme Court had dictated a sea change in how jurisdictional statutes are viewed. In Kontrick v. Ryan and other cases, the Supreme Court instructed that jurisdictional rules are reserved “only for prescriptions delineating the classes of cases (subject-matter jurisdiction) and the persons (personal jurisdiction) falling within a court’s adjudicatory authority.” As the 11th Circuit admitted, “the significance of this distinction was that, unlike a jurisdictional rule, a claim processing rule can be forfeited by a party.”

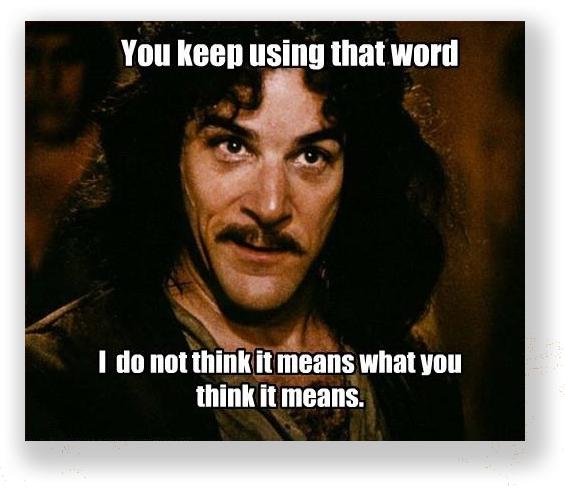

Kontrick and its line of cases recognized, as the appellate court noted, that “the “term ‘jurisdiction’ has become ‘a word of many, too many, meanings.” It should be reserved only for statutes that delineate the court’s adjudicatory authority over classes of cases and persons, not to statutes – such as Sec. 851 – that only “limit a court’s actions in a case in which the court’s underlying authority to decide the matter is unquestioned.”

Sec. 851, the Circuit ruled, is a “claim processing rule” that “seeks to promote the orderly progress of litigation by requiring that the parties take certain procedural steps at certain specified times.” First, the Court said, “it is clear that Sec. 85l’s notice requirement does not affect the district court’s subject-matter jurisdiction over cases involving offenses against the laws of the United States. To the contrary, that authority is plainly vested in the district courts by Congress… That Sec. 851 is denuded of any jurisdictional component is evidenced by the fact that the district court had the lawful power to accept DiFalco’s plea and impose a sentence upon him. And, indeed, it had the statutory authority to impose the very same 240-month sentence even without the filing of any Sec. 851 notice.”

Sec. 851’s requirements are not jurisdictional, the Circuit said, and, thus, may be waived. Mike “knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to challenge the Sec. 851 notice when he signed the plea agreement. The Court held that “upon a fair review of this record, we are satisfied that DiFalco knowingly and voluntarily waived his right to appeal his sentence. Thus, we dismiss his appeal.”

United States v. DiFalco, Case No. 15-14763 (11th Cir. Sept. 20, 2016)