We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

MAN BITEMARKS DOG

The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology released its report yesterday on the state of forensic science used in criminal courts, and it was every bit as scathing as the Wall Street Journal predicted it would be at the end of last month.

The report, written by scientists who carefully assess forensic methods according to scientific standards, found that many forensic techniques do not pass scientific muster – and thus are not ready for courtroom application.

The report, written by scientists who carefully assess forensic methods according to scientific standards, found that many forensic techniques do not pass scientific muster – and thus are not ready for courtroom application.

Last year, the Department of Justice examined its own performance in the analysis of hair samples – once used to identify potential suspects, but a practice that was discontinued in 1996 – and found FBI agents had “systematically overstated the method’s accuracy in court, including at least 35 death penalty cases,” according to Ars Technica.

This was hardly the only problem. Problems with forensic evidence have plagued the criminal-justice system for years, Ars Technica said. Faith in the granddaddy of all forensic-science methods—latent fingerprint comparison—was shaken in 2004 when the FBI announced that a print recovered from the Madrid train bombing was a perfect match with American lawyer Brandon Mayfield. Spanish authorities promptly discovered that the print belonged to someone else.

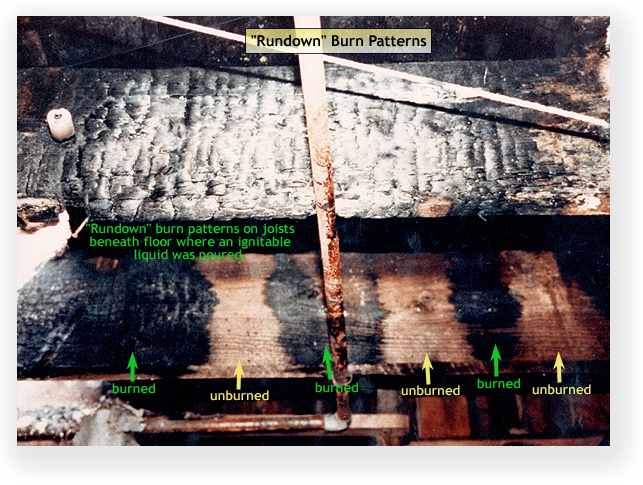

As Judge Alex Kozinski described it in Tuesday’ Wall Street Journal, “Doubt turned to horror when studies revealed that certain types of forensic science had absolutely no scientific basis. Longstanding ideas about ‘char patterns’ that prove a fire was caused by arson have been discredited. Yet at least one man, Cameron Todd Willingham of Texas, was executed based on such mumbo jumbo.”

The PCAST report analyzes DNA, bite mark, latent fingerprint, firearms, footwear and hair analysis techniques. The report finds that all of them have problems when it comes to operating on a firm scientific footing, and it concludes that forensic science needs “to take its name seriously.”

Only the most basic form of DNA analysis is scientifically reliable, the study indicates. Some forensic methods have significant error rates and others are rank guesswork. “The prospects of developing bitemark analysis into a scientifically valid method” are low, according to the report. “In plain terms,” Judge Kozinski wrote, “Bitemark analysis is about as reliable as astrology. Yet many unfortunates languish in prison based on such bad science.”

Even methods valid in principle become unreliable in practice. Forensic experts are “hired guns,” and the ones working for the prosecution sometimes see it as their job – if not required to keep the prosecution work coming – to get a conviction. This can lead and has led them to fabricate evidence or commit perjury. Some forensic examiners are poorly trained and supervised, and overstate the strength of their conclusions by claiming that the risk of error is “vanishingly small,” “essentially zero,” or “microscopic.” The report says that such claims are hyperbole, “scientifically indefensible,” but jurors generally take them at face value when presented by government witnesses who are certified as scientific experts.

The report recommends that DOJ take the lead in ensuring that (1) “forensic feature-comparison methods upon which testimony is based have been established to be foundationally valid with a level of accuracy suitable to their intended application;” and (2) “the testimony is scientifically valid, with the expert’s statements concerning the accuracy of methods and the probative value of proposed identifications being constrained by the empirically supported evidence and not implying a higher degree of certainty.”

The report also calls on DOJ to review, with scientific assistance, which forensic methods “lack appropriate black-box studies necessary to assess foundational validity.” The report specifically denounced footwear and hair analysis as resting on insufficient scientific foundation, and nearly ridiculed bite mark analysis as voodoo science. PCAST suggested that there could be more, with Judge Kozinski noting that arson burn pattern analysis should be near the top of the list.

Additionally, the panel called on DOJ to adopt uniform guidelines on expert testimony that ensure that “quantitative information about error rates” is provided to the jury, and when such information is not available, that should be disclosed, too. The report recommends that “in testimony, examiners should always state clearly that errors can and do occur, due both to similarities between features and to human mistakes in the laboratory,” which is about as likely as a snowstorm at a July 4th picnic.

As unlikely as prosecution cooperation with scientific accuracy might be, the report nevertheless is a much-needed stand against rampant junk science in the courtroom. As the Washington Post put it, the report “builds upon mounting evidence that certain types of ‘forensic feature-comparison methods’ may not be as reliable as they have long appeared. A recent, unprecedented joint study by the Innocence Project and the FBI looked at decades of testimony by hair examiners in criminal cases — and found flaws in the testimony an astonishing 95 percent of the time. In a number of serious felonies, DNA testing has revealed that bite-mark evidence underpinning convictions was simply incorrect. More generally, faulty forensic evidence has been found in roughly half of all cases in which post-conviction DNA testing has led to exoneration.”

Executive Office of the President, President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report To The President: Forensic Science in Criminal Courts: Ensuring Scientific Validity of Feature-Comparison Methods (Sept. 20. 2016)