We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

LOOSE LIPS SINK SHIPS

It’s an article of faith among federal inmates that they can file some kind of motion with the district court to get their grand jury materials, so they may comb through them for grist to use in a post-conviction motion.

Rule 6(e)(3)(E)(ii) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure provides that a court “may authorize disclosure… of a grand jury matter at the request of a defendant who shows that a ground may exist to dismiss the indictment because of a matter that occurred before the grand jury…” Thus, such inmate motions are almost always shot down, because district courts invoke an “exclusivity rule” that Rule 6(e)(3)(E) prohibits giving anyone grand jury materials unless one of the exceptions listed in subsection (e)(3) is met. Ever. No exceptions.

But now, a 7th Circuit decision handed down last week may sound the death knell for the “exclusivity rule.”

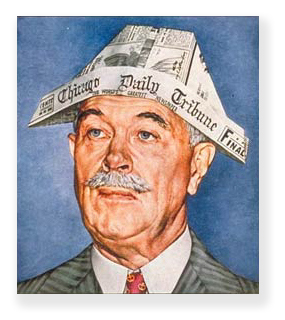

In 1942, the United States won a crucial naval victory at the Midway Islands, sinking a Japanese carrier task force and turning the tide of war in the Pacific. The enemy planned an attack on some Alaskan islands, to draw out U.S. aircraft carriers in order to destroy them. The Navy didn’t fall for the juke, and instead pulled off a stunning win.

When news broke of the victory, the Chicago Tribune printed a story that reported – accurately, it turns out – that the U.S. Navy knew in advance that the Alaskan attack was a distraction. President Roosevelt exploded when he saw the story, because it implied the U.S. had broken the Japanese naval codes (which it had). The President ordered a criminal investigation into the Tribune, which was owned by one of his political enemies, but the grand jury ended up returning no indictments.

About 70 years later, Elliot Carlson – a journalist and historian with a special expertise in naval history – petitioned the federal court for release of the Tribune grand jury materials for a book he is writing about the investigation. The government conceded there remain no interests favoring continued secrecy, but still resisted release of the materials, the 7th Circuit explained, arguing “that no one (as far as we can tell) has the power to release these documents except for one of the reasons enumerated in Rule 6(e)(3)(E).”

The appellate court ruled that Rule 6(e) is a permissive rule, not a mandatory one. It does not prevent the court from releasing grand jury materials where it believes release to be appropriate. Instead, the rule only directs that release always should be considered appropriate in the situations listed in subsection 6(e)(3). The district court’s “limited inherent supervisory power has historically included the discretion to determine when otherwise secret grand-jury materials may be disclosed,” the 7th Circuit said. “Prior to the adoption of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, the Supreme Court held that release of sealed grand jury materials ‘rests in the sound discretion of the [trial] court’ and ‘disclosure is wholly proper where the ends of justice require it.’ The advent of the Criminal Rules did not eliminate a district court’s inherent supervisory power as a general matter.”

The Court of Appeals held that Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 57(b) “recognizes that the rules are not designed to be comprehensive; instead, it says, ‘when there is no controlling law … [a] judge may regulate practice in any manner consistent with federal law, these rules, and local rules of the district.’ This Rule has remained substantively the same since the original 1944 version. To be sure, the court is powerless to contradict the Rules where they have spoken, just as the court cannot contradict a statute, [citing] Carlisle v. United States,); Bank of Nova Scotia v. United States. But it is Rule 57(b), not Carlisle or Bank of Nova Scotia, that informs us what a court may do when the Rules are silent.”

The Court of Appeals held that Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 57(b) “recognizes that the rules are not designed to be comprehensive; instead, it says, ‘when there is no controlling law … [a] judge may regulate practice in any manner consistent with federal law, these rules, and local rules of the district.’ This Rule has remained substantively the same since the original 1944 version. To be sure, the court is powerless to contradict the Rules where they have spoken, just as the court cannot contradict a statute, [citing] Carlisle v. United States,); Bank of Nova Scotia v. United States. But it is Rule 57(b), not Carlisle or Bank of Nova Scotia, that informs us what a court may do when the Rules are silent.”

It is doubtful that the Circuit’s ruling declares open season on novel claims justifying disclosure of grand jury materials, especially for defendants and former subjects of such investigations. The appeals panel noted that the “district court engaged in a thoughtful and comprehensive analysis of the pros and cons of disclosure before granting Carlson’s request, and we are content to let its analysis stand.” Nevertheless, district court denials of requests for release of grand jury materials clearly may no longer rely on rote application of the “exclusivity” rule.

Carlson v. United States, Case No. 15-2972 (7th Cir., Sept. 15, 2016)