We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just starting to post pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

STINGRAY SEARCH REQUIRES WARRANT

The DEA was stalking Washington Heights, New York, looking to bust an international drug ring. Agents got a warrant to pull cell site records on Ray Lambis’s smartphone, but the information they got only narrowed their search to a street corner that was home to several apartment buildings.

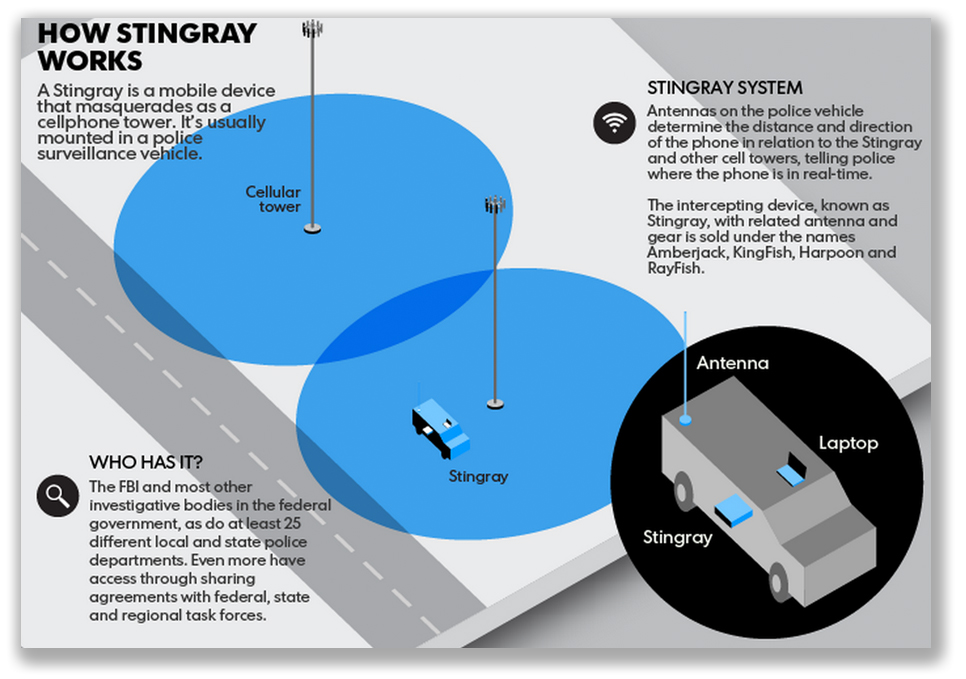

The agents decided to try for something more accurate, so they brought in a Stingray, a device that spoofed cellphones into thinking it was a cellphone tower and transmitted. So fooled, the phones transmitted identifying information to the Stingray every 7 seconds, letting the DEA home in on the exact location of the phone. The agents were moving fast, so they did not bother with a search warrant. Sure enough, the Stingray led agents to Ray’s dad’s apartment, and he let them search the place.

The agents decided to try for something more accurate, so they brought in a Stingray, a device that spoofed cellphones into thinking it was a cellphone tower and transmitted. So fooled, the phones transmitted identifying information to the Stingray every 7 seconds, letting the DEA home in on the exact location of the phone. The agents were moving fast, so they did not bother with a search warrant. Sure enough, the Stingray led agents to Ray’s dad’s apartment, and he let them search the place.

Yesterday, a Southern District of New York judge threw out the evidence they obtained from the search, holding that a Stingray search requires a search warrant. The DEA argued that Ray Lambis had not expectation of privacy in the pings his phone emanated. But relying on the 2001 Supreme Court decision in Kyllo v. United States, the District Court said “the DEA’s use of the cell-site simulator to locate Lambis’s apartment was an unreasonable search because the “pings” from Lambis’s cell phone to the nearest cell site were not readily available “to anyone who wanted to look” without the use of a cell-site simulator. The DEA’s use of the cell-site simulator revealed ‘details of the home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion,’ namely, that the target cell phone was located within Lambis’s apartment. Moreover, the cell-site simulator is not a device ‘in general public use.’ In fact, the DEA agent who testified at the hearing had never used one.”

The Court concluded that “The use of a cell-site simulator constitutes a Fourth Amendment search within the contemplation of Kyllo. Absent a search warrant, the Government may not turn a citizen’s cell phone into a tracking device.”

Opinion and Order, United States v. Lambis, Case No. 15cr734 (S.D.N.Y. July 12, 2016)