We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

COMPASSIONATE RELEASE ON DECK AT SUPREME COURT

In an unusual Friday evening order, the Supreme Court last week granted review of two more compassionate release cases, perhaps adding them to the one compassionate release case already on its docket for next fall or maybe issuing two separate decisions interpreting 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) in the same Term.

In an unusual Friday evening order, the Supreme Court last week granted review of two more compassionate release cases, perhaps adding them to the one compassionate release case already on its docket for next fall or maybe issuing two separate decisions interpreting 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) in the same Term.

Two weeks ago, the Court granted review to Fernandez v. United States, a case asking whether a combination of “extraordinary and compelling reasons” supporting a sentence reduction under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) can include reasons that may also be grounds for setting aside a sentence under 28 USC § 2255.

On Friday, the Court added Rutherford v. United States and Carter v. United States to the docket. The two cases are consolidated in one proceeding. Whether Fernandez will become part of that decision or become its own opinion has not yet been announced.

Rutherford and Carter ask whether in adopting new Guideline 1B1.13(b)(6), effective in November 2023, the Sentencing Commission exceeded its authority. That Guideline directs that a change in the law that means a prisoner’s current sentence could no longer be imposed–along with other factors–can be an “extraordinary and compelling reason” for compassionate release under the statute.

Rutherford and Carter ask whether in adopting new Guideline 1B1.13(b)(6), effective in November 2023, the Sentencing Commission exceeded its authority. That Guideline directs that a change in the law that means a prisoner’s current sentence could no longer be imposed–along with other factors–can be an “extraordinary and compelling reason” for compassionate release under the statute.

In one of the cases, defendant Daniel Rutherford committed two robberies using a gun in over a 5-day period. Using a gun in two robberies netted Dan two convictions for using a gun in a robbery (a violation of 18 USC § 924(c)). He was sentenced to 32 years for the two § 924(c)s, seven years for the one and 25 years for the second.

If Daniel had been sentenced after the First Step Act passed, he would have received a 14-year mandatory minimum for his two 18 USC 924(c) convictions, seven apiece. First Step amended § 924(c) to clarify that the 25-year sentence for a second conviction only applied after a defendant had been convicted of § 924(c) once already. But before First Step, courts held that if a second § 924(c) was committed even a day after the first one, the 25-year minimum applied to the second one.

In the second case, Johnnie Carter, convicted of multiple bank robberies in 2007, argued that if he had been sentenced after First Step, he would have 21 years of mandatory time instead of the 70 years he is serving.

The Sentencing Commission’s enabling law directs it to define what constitutes an “extraordinary and compelling reason” for compassionate release. Nevertheless, some circuit courts have held that because the First Step Act changed § 924(c) but did not do so retroactively, the Commission exceeded its authority in making the disparity due to those changes in the law an element of compassionate release.

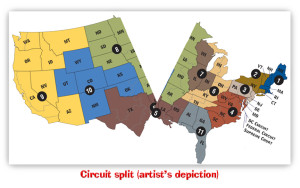

The 1st, 4th, 9th and 10th Circuits have OK’d allowing courts to consider the changes. The 3rd and 11th have gone the other way. Just a month ago, the 6th Circuit joined the naysayers, ruling in United States v. Bricker that adoption of § 1B1.13(b)(6) exceeded the Commission’s authority.

The 1st, 4th, 9th and 10th Circuits have OK’d allowing courts to consider the changes. The 3rd and 11th have gone the other way. Just a month ago, the 6th Circuit joined the naysayers, ruling in United States v. Bricker that adoption of § 1B1.13(b)(6) exceeded the Commission’s authority.

It does not overstate the case to say that SCOTUS’s holdings in Fernandez, Rutherford and Carter will define the future of compassionate release. The cases won’t be argued until late next fall or in early 2026, with a decision due by about a year from now.

Rutherford v. United States, Case No. 24-820 (Supreme Ct, petition for cert granted June 6, 2025)

Carter v. United States, Case No. 24-820 (Supreme Ct, petition for cert granted June 6, 2025)

Fernandez v. United States, Case No. 24-556 (Supreme Ct, petition for cert granted May 27, 2025)

United States v. Bricker, Case No 24-3286, 135 F.4th 427 (6th Cir. Apr 22, 2025)

Courthouse News Service, Justices take on sentencing reform issues, IQ tests for disabled facing death row (June 6, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root