We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BEATING FEET

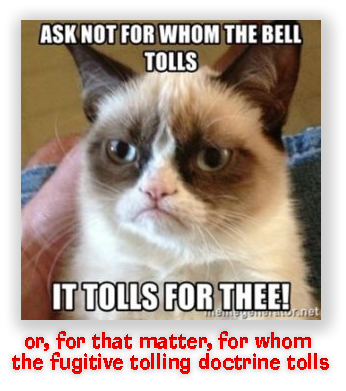

The fugitive tolling doctrine holds that if you are a fugitive – say as an escapee, or you jump bond – your sentence doesn’t run while you’re running. You’ve done 6 years of an 8-year sentence when you go on a furlough and don’t come back. When you’re finally caught, you still have those final two years to do (not to mention a ton of additional time for the escape).

The fugitive tolling doctrine holds that if you are a fugitive – say as an escapee, or you jump bond – your sentence doesn’t run while you’re running. You’ve done 6 years of an 8-year sentence when you go on a furlough and don’t come back. When you’re finally caught, you still have those final two years to do (not to mention a ton of additional time for the escape).

Federal sentencing law provides not only for prison, but also for a term of what is known as “supervised release” after the sentence ends. During the term of supervised release – usually three to five years long – the former inmate is expected to keep a job, follow a list of rules imposed by the court as well as the often random and irrational diktats of a probation officer, and fill out monthly reports that are little more than traps for the unwary.

Examples, you ask? A standard condition of supervised release – imposed by the court when a defendant is sentenced – is that the person on supervised release not associate with any person convicted of a felony, unless granted permission to do so by the probation officer. The monthly report a defendant is required to file, however, makes the sweeping inquiry, “Did you have any contact with anyone having a criminal record?”

Examples, you ask? A standard condition of supervised release – imposed by the court when a defendant is sentenced – is that the person on supervised release not associate with any person convicted of a felony, unless granted permission to do so by the probation officer. The monthly report a defendant is required to file, however, makes the sweeping inquiry, “Did you have any contact with anyone having a criminal record?”

Given that traffic offenses are mostly criminal misdemeanors, albeit minor, a defendant can hardly step outside of the house without having contact with someone with a criminal record. ‘Nitpicking’? you say. Maybe, but false statements on the form can result in the Probation Officer filing a violation report with the court that can result in additional prison time. Nitpicking under threat of imprisonment is serious business.

Statistics show that about one out of five people on supervised release are ‘violated,’ with most violations falling into the Grade C-level of violations, the least serious category reserved for things such as, say, false statements in the monthly report.

Jim Talley didn’t much like those odds, much less the irritation of regular meetings with his Probation Officer and filing monthly reports. After a little more than two years of supervised release, he had had enough. He simply stopped seeing his Probation Officer, stopped filing reports, and even moved without giving his PO the new address. In modern terminology, the Probation Office got ghosted worse than the other side of a blind date from hell.

Jim Talley didn’t much like those odds, much less the irritation of regular meetings with his Probation Officer and filing monthly reports. After a little more than two years of supervised release, he had had enough. He simply stopped seeing his Probation Officer, stopped filing reports, and even moved without giving his PO the new address. In modern terminology, the Probation Office got ghosted worse than the other side of a blind date from hell.

Right before his supervised release was to expire, the PO filed a violation warrant with the court. The warrant never caught up to Jim, because – as noted – he had moved without leaving the Probation Office a forwarding address.

A year after his supervised release expired, Jim was charged with Florida domestic battery. When he got arrested, he was served with the supervised release violation. Before his hearing, the PO amended Jim’s plain vanilla failure-to-report charges to include the much more serious allegation that Jim had committed new criminal conduct by being accused of domestic battery (a Grade A violation that will buy you a boatload of more prison time).

The district court found him guilty of the supervised release infractions, and gave him an extra 18 months. Last week, the 11th Circuit vacated the sentence and sent the case back.

The issue was whether the district court could punish Jimbo for new criminal conduct for a crime that happened after his supervised release expired. Applying a judicially crafted “fugitive tolling doctrine” for supervised release, the government argued that a sentencing court may toll an offender’s term of supervised release during any period that he or she evades supervision. Because Jimmy was a fugitive from 2020 until his 2022 battery arrest, the government contended, his term of supervision was on hold until he was caught rather than expiring in 2021 as scheduled.

The issue was whether the district court could punish Jimbo for new criminal conduct for a crime that happened after his supervised release expired. Applying a judicially crafted “fugitive tolling doctrine” for supervised release, the government argued that a sentencing court may toll an offender’s term of supervised release during any period that he or she evades supervision. Because Jimmy was a fugitive from 2020 until his 2022 battery arrest, the government contended, his term of supervision was on hold until he was caught rather than expiring in 2021 as scheduled.

The 11th noted that the circuits are divided over the application of “fugitive tolling” to terms of supervised release, with the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 9th applying the doctrine. But the 11th agreed with the 1st Circuit that there is no such animal.

The justifications for fugitive tolling in other contexts, the Circuit observed — such as prison escapes — do not apply to the context of supervised release. The fugitive tolling doctrine is meant to ensure that an original sentence is served, not to increase a sentence’s length. Endorsing the government’s theory of tolling, the 11th said, “would require us to hold that the supervised release clock stopped whenever Talley first absconded, but the sentence itself (i.e., the conditions of supervised release) remained in effect until he was found. But it makes very little sense to conclude that Talley was not subject to his supervised release conditions in May 2022 for the purposes of fugitive tolling, while simultaneously concluding that he violated his conditions of supervision at that time. As we have recognized in another context, ‘a supervised release order cannot simultaneously be suspended and actively in effect’.”

The justifications for fugitive tolling in other contexts, the Circuit observed — such as prison escapes — do not apply to the context of supervised release. The fugitive tolling doctrine is meant to ensure that an original sentence is served, not to increase a sentence’s length. Endorsing the government’s theory of tolling, the 11th said, “would require us to hold that the supervised release clock stopped whenever Talley first absconded, but the sentence itself (i.e., the conditions of supervised release) remained in effect until he was found. But it makes very little sense to conclude that Talley was not subject to his supervised release conditions in May 2022 for the purposes of fugitive tolling, while simultaneously concluding that he violated his conditions of supervision at that time. As we have recognized in another context, ‘a supervised release order cannot simultaneously be suspended and actively in effect’.”

The case was remanded for resentencing on Jim’s failure-to-report violations but not the new criminal conduct battery complaint.

U.S. Probation Office, Standard Monthly Report form

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Federal Probation and Supervised Release Violations (July 28, 2020)

United States v. Talley, Case No 22-13921, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 23800 (11th Cir., September 7, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root