We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

PLRA EXHAUSTION REQUIREMENT EXCUSED IF INMATE UNABLE TO COMPLY

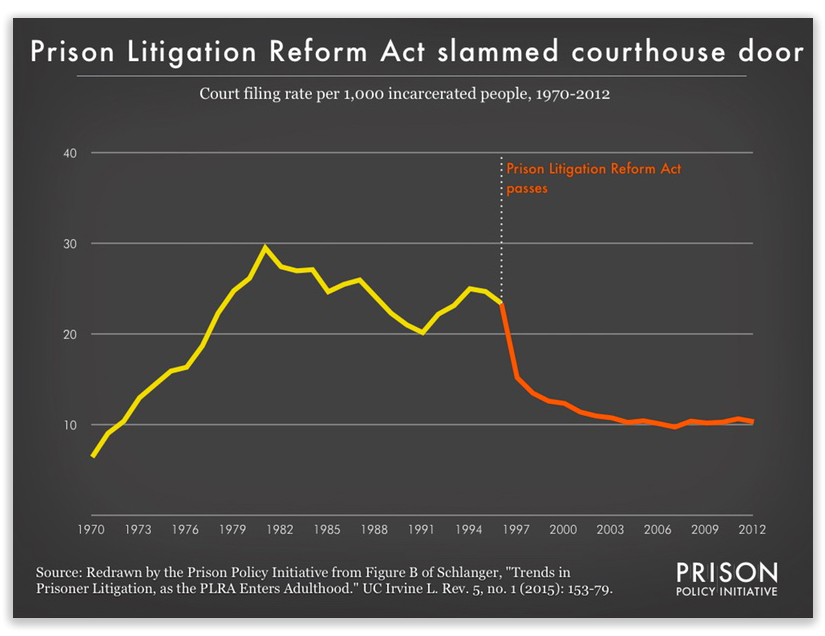

The Prison Litigation Reform Act was adopted in the 1990s to make it more procedurally complex for inmates to file civil actions. One provision of the PLRA requires a prisoner to exhaust all available administrative remedies before filing a federal lawsuit. Not meeting this exhaustion requirement usually gets an inmate civil action tossed out.

The Prison Litigation Reform Act was adopted in the 1990s to make it more procedurally complex for inmates to file civil actions. One provision of the PLRA requires a prisoner to exhaust all available administrative remedies before filing a federal lawsuit. Not meeting this exhaustion requirement usually gets an inmate civil action tossed out.

Rodolph Lanaghan is a very ill Wisconsin state prison inmate. Wisconsin prison regs require an inmate to file a grievance within 14 days of the occurrence giving rise to the complaint. Rodolph, who suffers from a severe degenerative muscle disease, filed a federal suit under 42 USC 1983, alleging state authorities were deliberately indifferent to his medical needs, and this violated his 8th Amendment rights.

The problem is that he did not file a state prison grievance first. After Rodolph was released from the hospital back into general population, a fellow inmate tried to sit with him in the day room to prepare a grievance on the prescribed form. But all the rec tables were occupied, and Rodolph needed a flat surface to write on. The day room study tables were available, but a corrections officer (CO) denied him use of a study table because prison regulations stated that those were reserved for studying only.

Unable to secure a table, Rodolph – who lacked any stamina because of the disease – went back to his cell with the help of the other inmate. Rodolph “spent the next week trapped inside his own body, believing he was going to die,” before being sent back to the hospital for two months.

Unable to secure a table, Rodolph – who lacked any stamina because of the disease – went back to his cell with the help of the other inmate. Rodolph “spent the next week trapped inside his own body, believing he was going to die,” before being sent back to the hospital for two months.

He got out of the hospital in March, but by then he was months past the deadline for filing a grievance. Therefore, he did not bother to try. Instead, he filed his lawsuit against the prison a few months later, in July. When Rodolph learned that the PLRA required he file a grievance before suing in order to exhaust his remedies, as the legal jargon puts it, he immediately did so, but the grievance was rejected as untimely.

At a hearing on whether Rodolph’s lawsuit complied with the PLRA, the Wisconsin institutional complaint examiner testified that Rodolph’s physical condition would have been good cause to extend the time for filing until March, had Rodolph only asked for a waiver to do so. Nothing, however, but nothing supported a delay from March until July, which was months after Rodolph’s return from the hospital.

The district court held Rodolph had failed to exhaust his administrative remedies with the prison, and his lawsuit should be tossed for violating the PLRA. Last week, however, the 7th Circuit reversed.

A prisoner does not have to follow the PLRA exhaustion requirements when the grievance procedure is not available to him or her. The appeals court noted that the proper focus is not whether the prison officials engaged in any misconduct that kept Rodolph from filing, but instead whether Rodolph was not able to file the grievance within the time period through no fault of his own. The availability of a grievance procedure is not an “either‐or” proposition, the Court said. “Sometimes grievances are clearly available; sometimes they are not; and sometimes there is a middle ground where, for example, a prisoner may only be able to file grievances on certain topics.” For that reason, the availability of a remedy is therefore a fact‐specific inquiry.

If the prison had a procedure under which grievance forms were provided to all inmates and they were required to fill them out without any assistance from others, the Court said, “that procedure might render the grievance remedy available for the majority of inmates, but the same procedure could render it unavailable for a subset of inmates such as those who are illiterate or blind, for whom either assistance or a form in braille would be necessary to allow them to file a grievance.”

Here, even though most inmates could have returned when a rec table was available, the Court said, and even though the COs were only following the rules in denying Rodolph a table, Rodolph’s particular circumstances (the disease) in conjunction with the CO’s decision made the prison grievance remedy unavailable to him.

Here, even though most inmates could have returned when a rec table was available, the Court said, and even though the COs were only following the rules in denying Rodolph a table, Rodolph’s particular circumstances (the disease) in conjunction with the CO’s decision made the prison grievance remedy unavailable to him.

What’s more, the Court said, Rodolph could not be held responsible for not filing after he got back from hospital months later. While nothing prevented him from filing the grievance immediately after he returned, a time when it might have been considered because his physical incapacity could have constituted good cause for the delay, nothing in the inmate handbook made him aware of such a procedure. The Court said that “a secret grievance procedure is no procedure at all, at least absent some evidence that the inmate was aware of that procedure.”

Lanaghan v. Koch, Case No. 17-1399 (7th Cir., Aug. 29, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root