We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

I DIDN’T MEAN IT LIKE THAT

Anyone who every entered a guilty plea (like 97% of federal prisoners) knows that at the change-of-plea hearing and in the plea agreement, the defendant signs off on a lot of fine print. Most of it goes by in a blur, and means little until much later, when the court and government beat the inmate over the head with “admissions” he made in writing and on the record.

Anyone who every entered a guilty plea (like 97% of federal prisoners) knows that at the change-of-plea hearing and in the plea agreement, the defendant signs off on a lot of fine print. Most of it goes by in a blur, and means little until much later, when the court and government beat the inmate over the head with “admissions” he made in writing and on the record.

Last week, the 7th Circuit suggested there were limits to holding a defendant to everything he or she said at the change-of-plea. Vance White pled guilty to a white-collar conspiracy. His plea agreement said, “beginning no later than in or around the fall of 2009 and continuing until at least in or around the summer of 2013…” Vance and his buddies had run a scheme to rip off merchants with bad checks. The only problem was that Vance had been locked up for most of the period, being actually free for only about a year of the 4-year conspiracy.

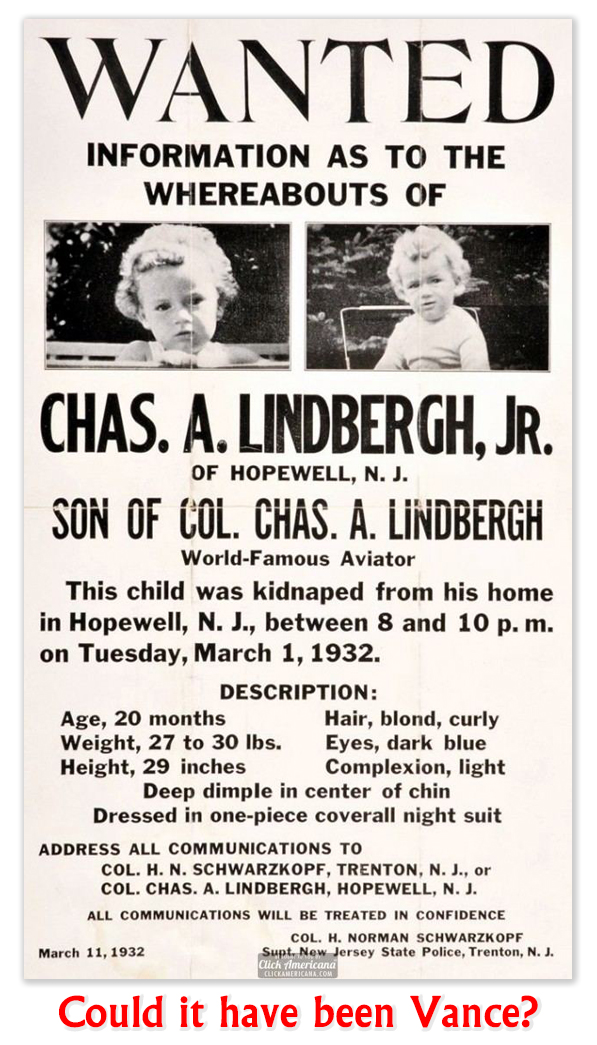

The mistake made a big difference in his Guidelines sentencing range, but the government was unapologetic. The AUSA argued that the truth didn’t matter, because Vance had admitted to all of the conspiracy involvement in his plea agreement. One presumes that if Vance had admitted to having assassinated President Kennedy, kidnapping the Lindbergh baby and masterminding 9/11, the government would have said that must be so, too.

Last week, the 7th Circuit decided that common sense should prevail. “As a general rule,” the Circuit said, “the government must show an aggravating offense characteristic under the Guidelines by a preponderance of the evidence, and this rule applies to the loss amount in a fraud offense… White’s guilty plea and his admission in the plea agreement are insufficient because they are too ambiguous on the key point. A plea agreement and admissions in a guilty plea hearing may of course establish a factual foundation for sentencing. The question here is just what White admitted. Our broad holdings about the evidentiary force of admissions in a plea agreement do not hold that a general admission in a plea agreement to a conspiracy or scheme spanning a certain time conclusively establishes individual participation during that entire time… White’s admission… is no better than a plea to an indictment — which admits only the essential elements of the offense. The beginning and end dates of a scheme are not essential elements.”

Last week, the 7th Circuit decided that common sense should prevail. “As a general rule,” the Circuit said, “the government must show an aggravating offense characteristic under the Guidelines by a preponderance of the evidence, and this rule applies to the loss amount in a fraud offense… White’s guilty plea and his admission in the plea agreement are insufficient because they are too ambiguous on the key point. A plea agreement and admissions in a guilty plea hearing may of course establish a factual foundation for sentencing. The question here is just what White admitted. Our broad holdings about the evidentiary force of admissions in a plea agreement do not hold that a general admission in a plea agreement to a conspiracy or scheme spanning a certain time conclusively establishes individual participation during that entire time… White’s admission… is no better than a plea to an indictment — which admits only the essential elements of the offense. The beginning and end dates of a scheme are not essential elements.”

United States v. White, Case No. 17-1131 (7th Cir. Mar. 2, 2018)

– Thomas L. Root