We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LISA DOES A ROAD TRIP 2

We reported last Friday on our trip to Washington for the “Advancing Justice, An Agenda for Human Dignity & Public Safety,” a conference sponsored by the Charles Koch Institute.

We reported last Friday on our trip to Washington for the “Advancing Justice, An Agenda for Human Dignity & Public Safety,” a conference sponsored by the Charles Koch Institute.

Today’s installment is Part 2 of our coverage:

SPEAKERS HINT AT SRCA PROSPECTS

The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017 (S.1917) is currently before a subcommittee of Senator Charles Grassley’s Judiciary Committee, but we’ve been there before. The 2015 version of the SRCA was approved by the Judiciary Committee, only to die on the Senate floor because leadership refused to bring it to a vote during a presidential election season.

What is lost in the story of the 2015-16 attempts to pass SRCA is that the bill that came out of the Committee was not the same bill that went in. Instead, a lot of the retroactivity written into the bill as drafted was taken out to please law-and-order conservatives like then-Sen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III (now Attorney General) and Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas).

Sen. Grassley, one of the SRCA sponsors, said at the Advancing Justice conference that the drafters of SRCA17 “kept the package balanced,” taking into account the views of the prior bill’s critics. He said that to those “wanting reasonable compromise, we will be willing partners.”

Sen. Grassley cited a number of pending criminal justice reform bills, including the Smarter Sentencing Act (S.1933), the Mens Rea Reform Act (S.1902) and the CORRECTIONS Act (S.1994), implying that one comprehensive piece of sentencing reform legislation may emerge from the Judiciary Committee that includes pieces of many or all of these bills.

Sen. Grassley’s favorable reference to the Smarter Sentencing Act is a lot different from what he thought two years ago, when he denounced “the arguments for the Smarter Sentencing Act [as] merely a weak attempt to defend the indefensible.” In fact, his complaint that mandatory minimum laws are “too severe” and give prosecutors too much discretion is a major change from 2015, when he complained in a Senate speech about the dangers of the “leniency industrial complex” and “a growing public misconception that mandatory sentences for drug offenders needed to be reduced.”

So are the stars aligned differently in this Congress? Marc Levin ot the Texas Public Policy Institute told a session on the future of sentencing reform that “part of the strategy is to have as comprehensive a [sentencing reform] package as possible, without making perfect the enemy of the good.” Both left- and right-wing politicians are working on sentencing reform, and Koch Industries general counsel Mark Holden thinks that Attorney General Sessions will not be an impediment to the bill’s passage, despite what Levin called Sessions’ “real difference of opinion” on sentencing reform.

So are the stars aligned differently in this Congress? Marc Levin ot the Texas Public Policy Institute told a session on the future of sentencing reform that “part of the strategy is to have as comprehensive a [sentencing reform] package as possible, without making perfect the enemy of the good.” Both left- and right-wing politicians are working on sentencing reform, and Koch Industries general counsel Mark Holden thinks that Attorney General Sessions will not be an impediment to the bill’s passage, despite what Levin called Sessions’ “real difference of opinion” on sentencing reform.

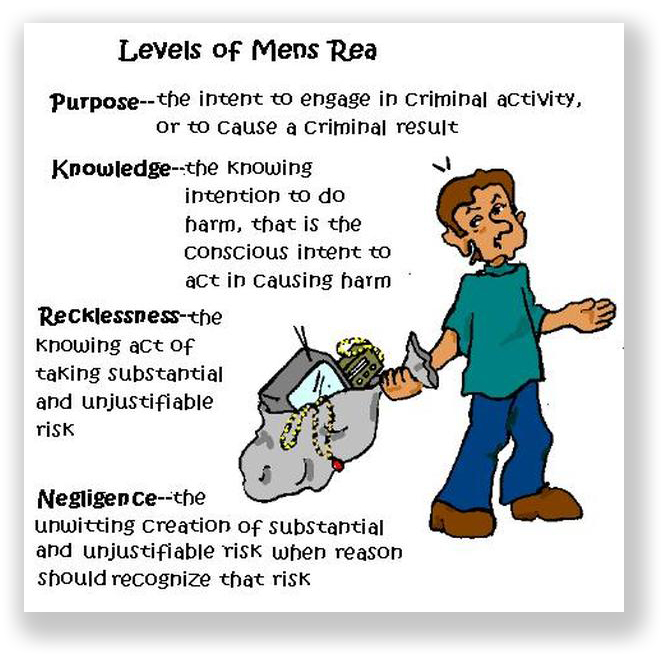

One potential stumbling block may be the Mens Rea Reform Act (S.1902). That Act would add a default rule for juries, requiring them to find criminal intent for federal offenses that don’t explicitly have an intent standard. If enacted, the Act would specify a default state of mind of “willfully,” and would require that unless the statute specified otherwise, AUSAs would have to prove the state of mind for every element of the offense. For example, a felon-in-possession charge under 18 USC 922(g) (which does not specify a state of mind) would require proof that the defendant possessed a gun that had traveled in interstate commerce intending to break the law. Currently, the government only must show the defendant knew he or she possessed a gun, not that the gun had traveled interstate and not that he or she knew the law prohibited possession.

Conservatives and criminal-defense organizations argue the measure is a necessary part of the congressional effort to reform sentencing and incarceration. Some Senate Democrats, however, fear the measure is far too sweeping and could be a back-door attack on federal regulations that police corporate behavior.

Conservatives and criminal-defense organizations argue the measure is a necessary part of the congressional effort to reform sentencing and incarceration. Some Senate Democrats, however, fear the measure is far too sweeping and could be a back-door attack on federal regulations that police corporate behavior.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D – Rhode Island), a member of the Judiciary Committee, told the Atlantic magazine last week that he wouldn’t support a sentencing reform bill containing the change in mens rea proposed by the MRRA. “It would turn me into a warrior against it,” he said. Chuck Schumer (New York), the Democratic leader in the Senate, also was quoted as saying he would oppose such a bill.

Ohio State University law professor and sentencing expert Douglas Berman wrote pessimistically last Friday about the effect the MRRA could have on sentencing reform:

I have said before and will say again that this kind of opposition to a reform designed to safeguard a fundamental part of a fair and effective federal criminal justice system shows just how we got to a world with mass incarceration and mass supervision and mass collateral consequences. Nobody seems willing or able to understand that making life easier for prosecutors anywhere serves to increase the size and reach and punitiveness of our criminal justice systems everywhere. In turn, if you want a less extreme and severe criminal justice system anywhere, the best way to advance the cause is by seeking and advocating to limit government prosecutorial powers everywhere.

Sentencing Law & Policy, Is it time for new optimism or persistent pessimism on the latest prospects for statutory federal sentencing reform? (Oct. 28, 2017)

The Atlantic, Could a Controversial Bill Sink Criminal-Justice Reform in Congress? (Oct. 26, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root