We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

NEW SENTENCING REFORM BILL TWEAKED

The text of S. 1917, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, has been released. SRCA17 is not just a rehash of the 2015 bill of the same name, but instead has some different and noteworthy provisions:

Serious drug felony: The federal catch-all drug crime statute – 21 USC 841 – raises the minimum sentence for people convicted of a prior “felony drug offense, “ which is a federal or state drug crime punishable by more than a year in prison. It does not matter if the defendant got probation for the prior offense, or if the prior offense happened 50 years ago.

Serious drug felony: The federal catch-all drug crime statute – 21 USC 841 – raises the minimum sentence for people convicted of a prior “felony drug offense, “ which is a federal or state drug crime punishable by more than a year in prison. It does not matter if the defendant got probation for the prior offense, or if the prior offense happened 50 years ago.

The result of this draconian provision is pretty clear. If someone who got probation 50 years ago for two pot-dealing felonies (remember Woodstock?), and was caught now with 50 grams of methamphetamine (imagine one-ninth of a pound, the weight of 36 paperclips), under 21 USC 841, he or she would get a mandatory life sentence. Naturally, results like this lead many defendants to take quick pleas and cooperate with the government, because whether to demand the enhanced penalty is solely up to the prosecutor.

SRCA17 would replace “felony drug offense” in 21 USC 841 with “serious drug felony.” A “serious drug felony” is defined as a felony conviction for which the defendant served more than a year in prison, and which happened within the past 15 years. Low-level indiscretions, as measured by the actual instead of the potential sentence and by the age of the conviction, will limit the draconian sentence enhancements under Sec. 841.

SRCA17 would replace “felony drug offense” in 21 USC 841 with “serious drug felony.” A “serious drug felony” is defined as a felony conviction for which the defendant served more than a year in prison, and which happened within the past 15 years. Low-level indiscretions, as measured by the actual instead of the potential sentence and by the age of the conviction, will limit the draconian sentence enhancements under Sec. 841.

Safety Valve: Currently, 18 USC 3553(f) contains what’s known as a “safety valve,” which relieves a drug defendant of an otherwise mandatory-minimum sentence if he or she meets certain criteria, including that there not be more than one prior criminal history point. Of course, a single drunk driving conviction can get you a point, and driving under a license suspension – which follows a DUI in most states like night follows day – will get you a second one.

SRCA17 raises the criminal history point threshold to 4 points, provided there’s no 3-point felony in the mix. At the same time, the “safety valve” would be modified to give a judge discretion to apply it even if the defendant’s points exceed four, if there’s reliable information indicates that the points “substantially over-represent the seriousness of the defendant’s criminal history or the likelihood that the defendant will commit other crimes.”

Drug 10-year Mandatory Minimum: Section 841 specifies that some quantities of drug involved in an offense will require imposition of a 5-year mandatory minimum, and other higher quantities will raise the mandatory minimum to 10 years. For example, in a crack cocaine offense, 28 grams or more requires a minimum 5-year sentence; 280 grams or more will get you at least 10.

Drug 10-year Mandatory Minimum: Section 841 specifies that some quantities of drug involved in an offense will require imposition of a 5-year mandatory minimum, and other higher quantities will raise the mandatory minimum to 10 years. For example, in a crack cocaine offense, 28 grams or more requires a minimum 5-year sentence; 280 grams or more will get you at least 10.

SRCA17 would give the judge the discretion in a 10-year case to drop the mandatory minimum to 5 years if the defendant has no drug or violent priors, did not use violence in the crime of conviction, was not a leader or organizer of the offense, and admitted the crime to the government.

Gun crime: Under 18 USC 924(c), a defendant who possesses, uses or carries a gun during a violent or drug trafficking crime must get a mandatory consecutive sentence of at least 5 years. The statute requires that if the defendant does it twice, the second (and all consecutive) offenses require a mandatory sentence of 25 years.

The government, being the government, long ago convinced the courts that the second offense does not require that the defendant have already been convicted of the first one (although that is what Congress meant to say). So if Donny Drugdealer sells me some weed on Monday while carrying a gun in his pocket, and then sells you some weed on Tuesday carrying the same gun, he has committed two drug trafficking offenses (worth, say, 30 months) and two separate 924(c) convictions. His sentence would be 30 months for the drugs plus 60 months for Monday’s gun plus 300 months for Tuesday’s gun. That’s 32 years plus in prison.

Just like SRCA15 would have done, SRCA17 changes 924(c) to require that a defendant be convicted of the first 924(c) offense before the 25 years for a subsequent offense be assessed.

Fair Sentencing Act: Before 2010, Congress believed crack cocaine was so dangerous that it considered one gram of crack to be equal to 100 grams of powder cocaine. In the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, Congress modified its stance, reducing the disparity to 18:1 from 100:1. The effect was to dramatically cut the mandatory minimum sentences being heaped on (mostly black) crack defendants for drug quantities that paled next to the piles of powder that were earning mostly white defendants much shorter sojourns with the Bureau of Prisons.

But to satisfy reluctant supporters like Sen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III – now Attorney General to a President who has denounced him as a moron – the FSA was not made retroactive for people already convicted and sentenced. SRCA17 tries to rectify this.

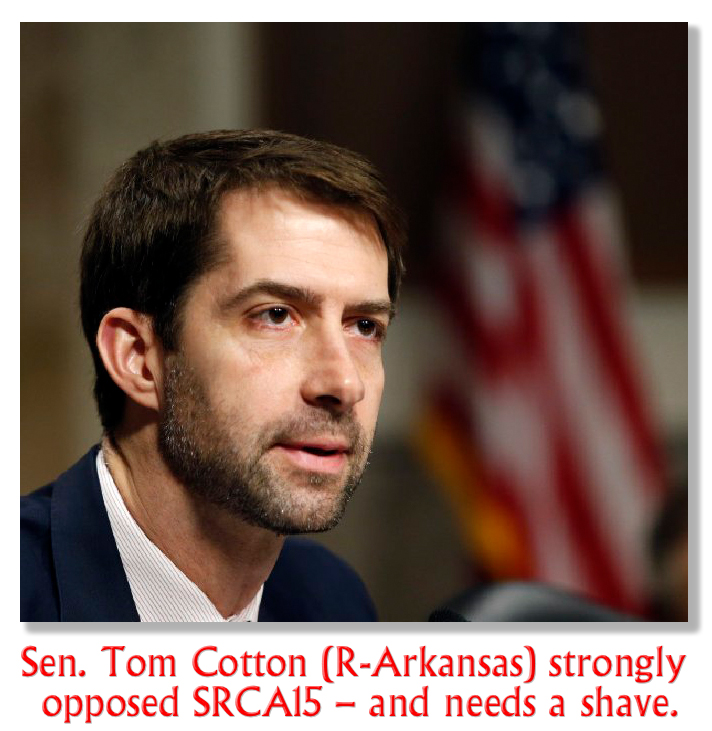

Retroactivity: SRCA15 originally proposed retroactivity for stacked 924(c) offenses, changed drug mandatory minimums and the FSA people. As the bill progressed through committee and the elections loomed, retroactivity  was stripped from the bill a piece at a time to mollify law-and-order people like Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) and then presidential-hopeful Ted Cruz. Even that was not enough to save the measure.

was stripped from the bill a piece at a time to mollify law-and-order people like Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) and then presidential-hopeful Ted Cruz. Even that was not enough to save the measure.

SRCA17 proposes a middle-of-the-road retroactivity provision that loosely tracks the reduction-of-sentence procedure under 18 USC 3582(c)(2). Retroactivity would apply to people with sentences enhanced by prior offenses, 924(c) stacked sentences and the FSA, but it would not be automatic.

Instead, the defendant would have to apply for it to the sentencing court, which then would have discretion to grant it. Some people would be outright excluded – for example, defendants who had brandished or fired the gun would be entitled to no 924(c) relief, and defendants convicted of a crime of violence would be denied any retroactive relief for a sentence enhanced by a prior crime. FSA people will not be disqualified because of priors, but in all cases, the trial judge is left with discretion whether to grant a reduction or not.

SRCA17 contains a few enhanced penalties for violent crimes and spouse-beating. Those proposals and the retroactivity provision seem to be an attempt to throw some red meat to the law-and-order lobby. Putting the district judge in the position to decide retroactivity on an individualized basis splits the baby down the middle, granting prisoners a chance to equalize their sentences with those being handed out to new defendants after the bill passes while not releasing prisoners wholesale (and giving the Jefferson Beauregard Sessionses of the world something to gripe about).

SRCA17 contains a few enhanced penalties for violent crimes and spouse-beating. Those proposals and the retroactivity provision seem to be an attempt to throw some red meat to the law-and-order lobby. Putting the district judge in the position to decide retroactivity on an individualized basis splits the baby down the middle, granting prisoners a chance to equalize their sentences with those being handed out to new defendants after the bill passes while not releasing prisoners wholesale (and giving the Jefferson Beauregard Sessionses of the world something to gripe about).

Tomorrow: Provisions in SRCA17 for good time credit and reentry assistance. No sex offenders need apply.

S.1917, Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017 (introduced Oct. 3, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root