We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

LET’S GO ROUND US UP SOME POOR BLACK DEFENDANTS…”

We recall a counter-culture cartoon from the early 1970s criticizing big business getting into the environmental business: one fat cat telling another, “We get paid to make the mess. We get paid to clean it up. Business couldn’t be better.”

The old punch line comes to mind every time we read another “stash house” reverse-sting case. The story line is well known to everyone except, it would seem, the black guys in the poor part of town. An ATF undercover officer convinces some poor sap to rob a fantasy drug “stash house” that invariably is alleged to contain 10 kilos of drug or more. The unemployed “mark,” who has a felony record that makes getting a job problematic, doesn’t have two nickels to rub together. But he can perform simple math, and the math is 10 kilos of coke at $40,000 a key divided five ways equals a bigger pile of money than he’s ever seen before. So he recruits some other guys as desperate as he is, and they all gather with whatever guns they can find, in order to set off with the undercover guy to the target stash house.

The old punch line comes to mind every time we read another “stash house” reverse-sting case. The story line is well known to everyone except, it would seem, the black guys in the poor part of town. An ATF undercover officer convinces some poor sap to rob a fantasy drug “stash house” that invariably is alleged to contain 10 kilos of drug or more. The unemployed “mark,” who has a felony record that makes getting a job problematic, doesn’t have two nickels to rub together. But he can perform simple math, and the math is 10 kilos of coke at $40,000 a key divided five ways equals a bigger pile of money than he’s ever seen before. So he recruits some other guys as desperate as he is, and they all gather with whatever guns they can find, in order to set off with the undercover guy to the target stash house.

There is no stash house, but there is a SWAT team ready to take them down.

The ATF manufactures the crime. The ATF performs the bust. Business couldn’t be better.

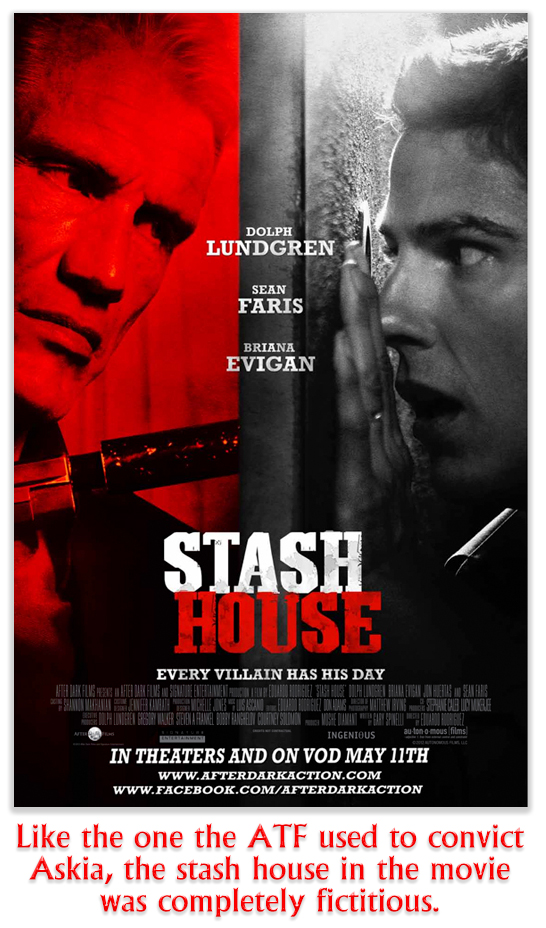

Notice we said “poor black guy.” That’s not a stereotype, but rather an acknowledgement of fact. In this case, acting on what appeared to be insider information from a drug courier, Askia Washington and his three co-conspirators planned to rob a Philadelphia “stash house” where they thought 10 kilos of cocaine were being stored for distribution. They discovered on the day of the robbery that the “stash house” was a trap set by ATF.

The cocaine did not exist, but the entirely fictitious 10 kilograms triggered a very real 20-year mandatory minimum for Askia, contributing to a total sentence of 264 months in prison — far more than even the statistics show that the defendants trapped in the reverse sting net are overwhelmingly black, so much so that some serious charges of discrimination have been raised against the practice.

From a defense perspective, it’s very hard to make a case for selective prosecution. The prevailing standard pretty much requires that you have the smoking gun in your hand in order to even win the right to engage in discovery to try to find the smoking gun. Exacerbating the problem is the obvious: you’re not arguing your client did not do what the indictment said he did, but rather arguing that how the government ensnared him is so contrary to fairness as to violate his right to due process of law.

The courts do not much like “stash house” cases, but they continue to hold their noses and uphold convictions. That happened earlier this week in Philadelphia, but the 86-page decision lightens the load for defendants attacking the “stash house” scheme and implies that the courts’ patience may be nearing an end.

The story is quotidian: Acting on what appeared to be insider information from a drug courier, Askia Washington and his three co-conspirators planned to rob a Philadelphia “stash house” where they thought 10 kilos of cocaine were being stored for distribution. They discovered on the day of the robbery that the “stash house” was a trap set by law enforcement. Their “courier” was an under ringleader of the conspiracy received.

The story is quotidian: Acting on what appeared to be insider information from a drug courier, Askia Washington and his three co-conspirators planned to rob a Philadelphia “stash house” where they thought 10 kilos of cocaine were being stored for distribution. They discovered on the day of the robbery that the “stash house” was a trap set by law enforcement. Their “courier” was an under ringleader of the conspiracy received.

His co-conspirators took pleas (getting sentences from 27 months to 180 months). Askia went to trial, beating an 18 USC 924(c) count but losing on the drug conspiracy and Hobbs Act counts. The jury found that the conspiracy involved at least 5 kilograms, and a very old drug possession conviction Askia had was used to increase the mandatory minimum sentence to 240 months.

Before trial, Askia tried to get government records to support his claim that Philadelphia-area “stash house” sting targets were selected by race, but the district court denied him on the ground that he could not show evidence of discriminatory effect and discriminatory intent, that is, evidence that similarly situated individuals of a difference race or classification were not prosecuted, arrested, or otherwise investigated.

This of course has the flavor of a dog chasing its tail. You need the evidence you’re trying to obtain in order to get permission to obtain it. But that has heretofore been the standard for getting the right to pursue a selective prosecution claim.

This of course has the flavor of a dog chasing its tail. You need the evidence you’re trying to obtain in order to get permission to obtain it. But that has heretofore been the standard for getting the right to pursue a selective prosecution claim.

With considerable reluctance, the 3rd Circuit upheld Askia’s conviction and sentence, but not without a lot of misgiving:

In sum, we conclude that the 5 kilograms of cocaine charged in the indictment and found by the jury did not amount to an impermissible manipulation of sentencing factors by the government. To the extent that the fictitious 10 kilogram quantity is relevant, we find too that Washington has shown neither improper manipulation nor prejudice. Nevertheless, we remind the government that we have expressed misgivings in the past about the wisdom and viability of reverse stash house stings. That this case fell on the safe side of the due process divide should not be taken to indicate that all such prosecutions will share the same fate. As one of our colleagues said in a prior case, “I do not find it impossible for the Government to exercise its discretion rationally to set up stash house reverse stings. But I share the concern that this practice, if not properly checked, eventually will find itself on the wrong side of the line.

The Circuit differentiated between “selective prosecution” claims and “selective enforcement” claims. “‘Prosecution’,” the 3rd said, “refers to the actions of prosecutors (in their capacity as prosecutors) and ‘enforcement’ to the actions of law enforcement and those affiliated with law-enforcement personnel.” The key distinction between prosecutors and law enforcement is that prosecutors are “protected by a powerful privilege or covered by a presumption of constitutional behavior”… while FBI and ATF agents “regularly testify in criminal cases” and have their credibility “relentlessly attacked by defense counsel.”

The Circuit held that in “stash house” cases, a district court may conduct a limited pretrial inquiry into the challenged law-enforcement practice on a proffer that shows some evidence of discriminatory effect, saying that “the proffer must contain reliable statistical evidence, or its equivalent, and may be based in part on patterns of prosecutorial decisions… even if the underlying challenge is to law enforcement decisions.”

The Circuit held that in “stash house” cases, a district court may conduct a limited pretrial inquiry into the challenged law-enforcement practice on a proffer that shows some evidence of discriminatory effect, saying that “the proffer must contain reliable statistical evidence, or its equivalent, and may be based in part on patterns of prosecutorial decisions… even if the underlying challenge is to law enforcement decisions.”

Although Askia’s conviction remains in place, the Circuit remanded the case for the district court to permit the limited discovery. If evidence of selective enforcement was developed, the district court is free to dismiss the indictment.

The lone dissenting judge blasted Askia’s 265-month sentence:

Surely, sentences should bear some rational relationship to culpability. Otherwise, the entire enterprise of criminal sanctions is reduced to little more than an abstract matrix of numbers and grids. Yet, on this record, there is absolutely nothing to suggest that Washington would not have conspired to rob a stash house containing, for example, a kilogram less than the 5-kilogram mandatory trigger. No mandatory minimum would have “applied” had this trap been baited with the illusion of a stash house containing four kilograms (translating roughly to upwards of $160,000 in value based on the trial testimony)—thereby placing him beyond the reach of the perceived need to impose a 20-year statutory mandatory minimum sentence.

United States v. Washington, Case No. 16-2795 (3rd Cir., August 28, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root