We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WANT AN INCREDIBLE SENTENCE BREAK? BE A COP.

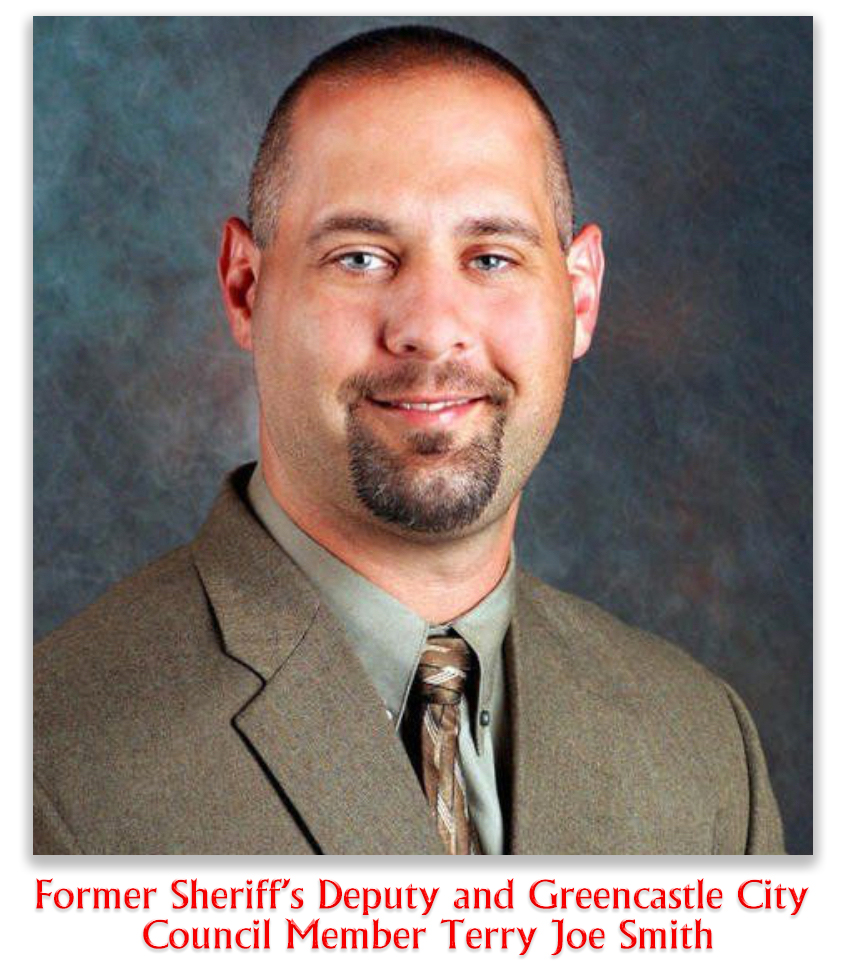

Terry Joe Smith was a bully. He liked to beat the crap out of people. But that kind of conduct is illegal for most bullies, so Terry Joe joined the Putnam County Sheriff’s Office as a deputy.

Putnam County, Indiana, with fewer people (40,000) than attend a typical Indiana University football game, does not appear to have much going for it. The official Putnam County visitors’ website, which hasn’t been updated in about 10 months, is mostly dedicated to ads for the next county to the west.

But, however humble, it was home to tiny (6’3”, 270-lb) Terry Joe, whose career included protecting (and representing on city council) the fine people of Greencastle. Terry Joe kept the citizenry safe b, among other things, punching an arrestee – who was under the control of four other cops – in the face with a closed fist, which two other deputies testified sound like “a tomato hitting a concrete wall,” sending the poor perp away in an ambulance. Terry Joe was impressed with that one, bragging afterward about the punch and making fun of the deputies who found his conduct objectionable.

But, however humble, it was home to tiny (6’3”, 270-lb) Terry Joe, whose career included protecting (and representing on city council) the fine people of Greencastle. Terry Joe kept the citizenry safe b, among other things, punching an arrestee – who was under the control of four other cops – in the face with a closed fist, which two other deputies testified sound like “a tomato hitting a concrete wall,” sending the poor perp away in an ambulance. Terry Joe was impressed with that one, bragging afterward about the punch and making fun of the deputies who found his conduct objectionable.

In another incident, Terry Joe was leading a drunken domestic violence defendant to the squad car. He lifted the handcuffed suspect into the air, threw him face-first onto the ground and drove his knee into the man’s back with such force that the man defecated on himself. Terry Joe liked that move, and told other deputies it wasn’t the first he’d made a defendant soil himself with a knee in the back.

He must have been very persuasive as a campaigner for city council. Greg Gianforte could have learned from this guy.

We had an old law partner who liked to say that “no thief steals only once.” Likewise with Terry Joe. He was prosecuted for the punch and knee incidents, but those were just the tip of the iceberg. Besides the incidents he liked to brag about, Terry Joe had beaten up juveniles at the correctional center, surreptitiously recorded inmate conversations, provided favored detainees with tobacco, and collected county pay while on the payroll of a private security company. Terry Joe even beat up a 3-year old (and his mother, when she tried to intervene). NYPD Blue’s Andy Sipowicz was once described by Jason Gay of the Boston Phoenix as being a “drunken, racist goon with a heart of gold.” Had Jason described Terry Joe, he would just shortened the description to one word: “goon.”

We had an old law partner who liked to say that “no thief steals only once.” Likewise with Terry Joe. He was prosecuted for the punch and knee incidents, but those were just the tip of the iceberg. Besides the incidents he liked to brag about, Terry Joe had beaten up juveniles at the correctional center, surreptitiously recorded inmate conversations, provided favored detainees with tobacco, and collected county pay while on the payroll of a private security company. Terry Joe even beat up a 3-year old (and his mother, when she tried to intervene). NYPD Blue’s Andy Sipowicz was once described by Jason Gay of the Boston Phoenix as being a “drunken, racist goon with a heart of gold.” Had Jason described Terry Joe, he would just shortened the description to one word: “goon.”

Terry Joe’s highjinks were finally too much for Putnam County. First, he was fired by the Sheriff for beating some prisoners and giving cigarettes to others, then fired from the Plainfield Juvenile Correctional Facility for beating two juveniles and lying about it, then fired by Putnam County for the “ghost employment” incident, and finally fired again by the Sheriff (who, incredibly enough, had rehired him) for the fist and knee incidents.

But nobody charged him criminally until the Feds came along, and a jury convicted him under 18 USC 242 of violating defendants’ rights under color of law. With a Guideline sentence of 33-41 months, the federal judge found Terry Joe had had a rough childhood, he was a hard worker, and the community supported him (at least, the ones he hadn’t made crap on themselves). Terry Joe got 14 months.

But nobody charged him criminally until the Feds came along, and a jury convicted him under 18 USC 242 of violating defendants’ rights under color of law. With a Guideline sentence of 33-41 months, the federal judge found Terry Joe had had a rough childhood, he was a hard worker, and the community supported him (at least, the ones he hadn’t made crap on themselves). Terry Joe got 14 months.

The 7th Circuit threw out the downward variance from the Guidelines as being leniency not supported by the record. The Circuit said,

although a sentence that low need not be unreasonable, the farther a judge strays from the guidelines range, “the more important it is that he give cogent reasons for rejecting the thinking of the Sentencing Commission.” We took issue with the court’s conclusion that Smith was unlikely to re-offend if he addressed his anger management issues. Nothing in the record described the anger management program that Smith was required to undergo as a condition of supervised release and there was reason to question the efficacy of such an undefined program in light of Smith’s history of violence and bizarre conduct towards the victims of his offenses of conviction.

The case went back to the district court, and by the time Terry Joe was resentenced, he had done his 14-month bit. At the resentencing, Terry Joe gave the judge an extended sob story about how hard prison was, how rubbing shoulders with other inmates gave him new-found respect for the people he used to beat up, and that he now knew that defendants (like himself) should be given short sentences. The district judge, no doubt shedding a tear, tiptoed through the sentencing factors of 18 USC 3553, and gave Terry Joe the same 14 months:

The case went back to the district court, and by the time Terry Joe was resentenced, he had done his 14-month bit. At the resentencing, Terry Joe gave the judge an extended sob story about how hard prison was, how rubbing shoulders with other inmates gave him new-found respect for the people he used to beat up, and that he now knew that defendants (like himself) should be given short sentences. The district judge, no doubt shedding a tear, tiptoed through the sentencing factors of 18 USC 3553, and gave Terry Joe the same 14 months:

I do not see any benefit in reincarcerating Mr. Smith. His anger control counseling would be interrupted. He will lose his job again. He will also disrupt the stability of his children, whom I assume have now adopted [sic] to having him back in the home.

On Monday, the 7th Circuit threw up its hands, threw out the sentence, and threw the case over to a new judge. The appeals court held the district judge erred procedurally by failing to adequately explain or justify the significantly below-guidelines sentence that he rendered. The district court relied on guidelines section 5K2.10, which lets a court depart downward if “the victim’s wrongful conduct contributed significantly to provoking the offense behavior.” But the district court made no finding that the detainees beaten by Terry Joe had done anything (other than be arrested) to “provoke” the bully deputy. “Nor,” the Circuit said, “did the court consider the factors set forth in the guidelines policy statement, such as the relative size and strength of the victim compared to the defendant, the persistence of the victim’s conduct, efforts by the defendant to prevent the confrontation, and the proportionality and reasonableness of the defendant’s response to the victim’s provocation, among other things.”

The 7th said Terry Joe’s crimes were plain vanilla “excessive force” crimes, and nothing about the “nature and circumstances” of the offense justified cutting Terry Joe a break. Terry Joe went to trial and never accepted responsibility for his conduct. Terry Joe tried at resentencing to “take ownership” of his crimes, but he did so without ever expressing remorse for, or even mentioning, the victims.

The appellate panel said

On release from prison, Smith reunited with his family, which continues to support him. He once again became employed, and began an anger management program. He completed his sentence without conduct violations. These are laudable, positive signs but Smith still has not admitted the conduct underlying his conviction or expressed remorse for the harms he caused. This relatively minor evidence of rehabilitation must be assessed in light of Smith’s history and characteristics. The government’s accounting of Smith’s appalling history includes an attack on a three-year-old child that left the child bruised and bleeding; an attack on that child’s mother when she tried to intervene to protect the child; unprovoked, premeditated beatings of two juveniles in custody followed by lies about the incident in the official record; other abuses of power over inmates at another facility; and the dishonest behavior of clocking in at two jobs at the same time. At the first sentencing, the court acknowledged that these prior incidents brought to light by the government came in “uncontroverted.” Smith has not challenged the government’s description of his history of violence and dishonesty. If there is a rationale to support a sentence that is less than half the low end of the guidelines, it is not apparent in the record here.

The panel ended the decision with a cryptic note that “Circuit Rule 36 shall apply on remand. “ Seventh Circuit Rule 36 requires assignment to a different judge if a case is remanded for a new trial, but does not normally apply where the remand is for resentencing. That the Circuit ordered reassignment to another judge suggests the extent to which the appellate court believed that this judge was so predisposed to be lenient because the defendant had been a cop that he could not be trusted to follow the appellate court’s instructions.

The panel ended the decision with a cryptic note that “Circuit Rule 36 shall apply on remand. “ Seventh Circuit Rule 36 requires assignment to a different judge if a case is remanded for a new trial, but does not normally apply where the remand is for resentencing. That the Circuit ordered reassignment to another judge suggests the extent to which the appellate court believed that this judge was so predisposed to be lenient because the defendant had been a cop that he could not be trusted to follow the appellate court’s instructions.

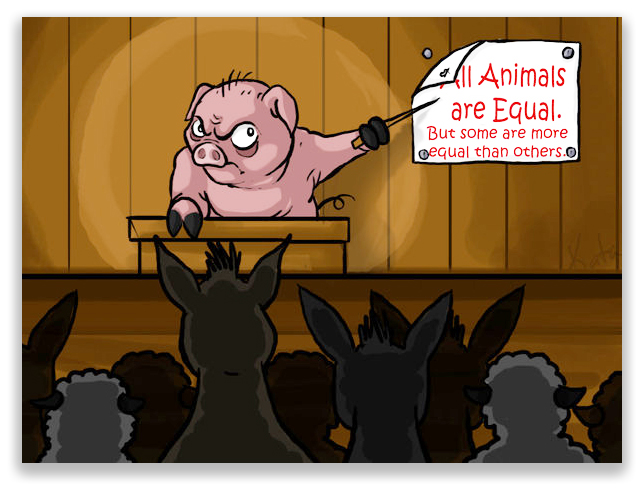

All defendants are equal, but some defendants – like cops – are more equal than others.

United States v. Smith, Case No. 16-2035 (7th Cir., June 19, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root