We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

HINT: IT AIN’T DRUGS AND IT AIN’T LONG SENTENCES

We are not much for writing book reviews. The last one we did was sometime in the mid-1970s in college journalism class. Occasionally, a book is published that just might change the arc of the debate, however, and John Pfaff’s new tome, Locked In, just might be such a book.

This is not beach reading. With a formidable array of statistics, dense text and a plethora of charts, Pfaff shows that some of the most cherished notions of the right and left are wrong. The War on Drugs caused mass incarceration? Wrong. Longer sentences have crowded our prisons? Wrong again.

This is not beach reading. With a formidable array of statistics, dense text and a plethora of charts, Pfaff shows that some of the most cherished notions of the right and left are wrong. The War on Drugs caused mass incarceration? Wrong. Longer sentences have crowded our prisons? Wrong again.

Pfaff argues convincingly that a significant cause of prison population growth is rising admissions, and he points an accusing finger at the increasing rate at which prosecutors filed felony charges during years when both crime rates and arrests fell.

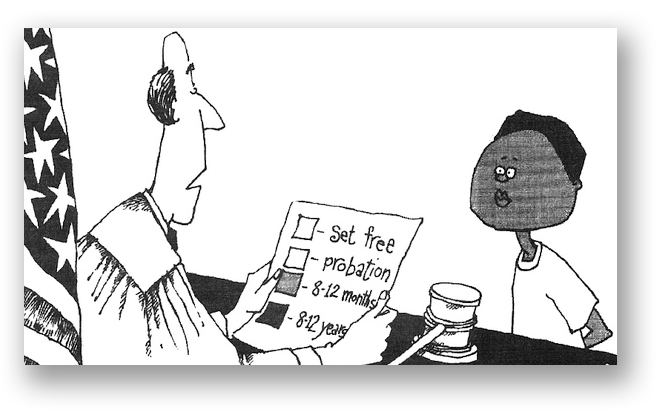

Most of the criminal justice debate has focused on rigid sentencing rules: mandatory minimum sentences, “truth in sentencing” laws that require offenders to serve at least 85% of their original sentence, and habitual criminal laws that can send away repeat offenders for decades, if not a lifetime. While criminal sentences in the U.S. are much longer than the international average, and while the records suggest the raw sentence is longer, Pfaff shows that the time actually served has grown very little.

The real problem, Pfaff says, is not “time served” but rather the sheer rate of admissions into prisons, which have skyrocketed since the 1980s. Sentencing reform legislation that does away with mandatory minimum sentences for low-level crimes may be worth doing, but it’s not going to affect mass incarceration.

Pfaff, a professor of both law and economics, says just 16% of the 1.3 million people in state prisons (where the vast majority of inmates are held) are there on drug offenses, while more than half are convicted of violent crimes. If everyone in state and federal prison serving a drug sentence was released, Pfaff writes, the US would still have 1.25 million people behind bars, an incarceration rate four times higher than in 1970.

What’s more, Pfaff points out, drug offenses don’t contribute to racial disparities in imprisonment. The percentage of whites sentenced for drug crimes (15%) is actually slightly higher than that for blacks (14.9%) and Hispanics (14.6%). Reducing sentences for nonviolent drug criminals would only have a small impact on mass incarceration.

What’s more, Pfaff points out, drug offenses don’t contribute to racial disparities in imprisonment. The percentage of whites sentenced for drug crimes (15%) is actually slightly higher than that for blacks (14.9%) and Hispanics (14.6%). Reducing sentences for nonviolent drug criminals would only have a small impact on mass incarceration.

By contrast, violent offenses explain the majority of mass imprisonment, driving racial disparities because the rate for whites (46.6%) is significantly lower than that for blacks (57.8%) and Hispanics (58.7%).

Pfaff favors “cutting long sentences for people convicted of violence, even for those with extensive criminal histories, since almost everyone starts aging out of crime by their 30s.” He also urges less reliance on prison and more on community-based anti-violence programs. Pfaff argues that the real concern is not sentence length, but serving any time in prison at all. Whether an inmate serve 12 or 16 months, he says, the impact is the same. Upon release, convicted felons have a hard time getting decent jobs or good housing. And with the odds heavily stacked against them, they’re more likely to reoffend.

“If we are serious about ending mass incarceration,” he argues, “we will have to figure out how to lock up fewer people who have committed violent acts and to incarcerate those we do imprison for less time.”

An interesting corollary argument – one we’ve long shared where firearms laws are concerned – was advanced by columnist Diane Dimond last week. She cited a 2014 National Research Council study that found “those committing crimes usually have no idea what kind of sentence their actions might net them and that ‘certainty of apprehension’ is far more important to them” than sentence length. The study reports that “arrests ensue for only a small fraction of all reported crimes.” By illustration, the number of reported robberies outnumber robbery arrests by about 4-to-1, and the offense-to-arrest ratio for burglaries is about 5-to-1. These ratios have “remained stable since 1980.”

An interesting corollary argument – one we’ve long shared where firearms laws are concerned – was advanced by columnist Diane Dimond last week. She cited a 2014 National Research Council study that found “those committing crimes usually have no idea what kind of sentence their actions might net them and that ‘certainty of apprehension’ is far more important to them” than sentence length. The study reports that “arrests ensue for only a small fraction of all reported crimes.” By illustration, the number of reported robberies outnumber robbery arrests by about 4-to-1, and the offense-to-arrest ratio for burglaries is about 5-to-1. These ratios have “remained stable since 1980.”

Dimond argues that “those bent on bad deeds know the odds of getting caught, which gives them a decisive advantage, so they take their chances.”

The Marshall Project, Everything you think you know about mass incarceration is wrong (Feb. 9, 2017)

Washington Post, What we get wrong about mass imprisonment in America (Feb. 8, 2017)

Commonwealth magazine, Is criminal justice reform misfiring? (Feb. 6, 2017)

Boston Globe, Why we should free violent criminals (Feb. 5, 2017)

Diane Dimond, Thinking Outside the Box on Sentencing Guidelines (Feb. 4, 2017)