We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WE’RE AT A “LOSS” TO EXPLAIN IT

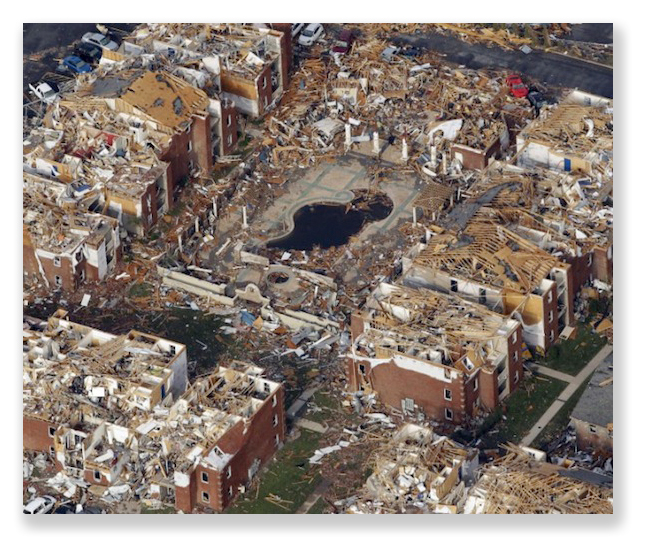

Tom Evans was a Colorado real estate developer who raised a pot full of investor money to renovate an apartment complex. The deal was completely legitimate, but rather risky.

When the deal started to go bad, Tom dumped $4.5 million of his own money into the project. Unfortunately, he also started commingling his money with the investors’ funds, and lying to the investors and bankers about how the deal was going.

When his fraud was discovered in 2007, a receiver took over the project. The receiver managed to convince investors to invest good money after bad to save the project. Alas, the rescue did not work, and the whole deal collapsed.

Tom was convicted of fraud, and sentenced to 168 months, chiefly because the district court held him responsible for a $12.3 million loss. The 10th Circuit reversed the sentence and sent the case back, telling the district court to determine “the reasonably foreseeable amount of loss to the value of the securities caused by Mr. Evans’ fraud.” The district court was “disregard any loss that occurred before the fraud began and account for the forces that acted on the securities after the fraud ended.”

In order to exclude harm preceding the fraud, the district court had to determine “the value of the securities at the time the fraud began.” But on remand, the government threw up its hands and said it could not do that. So the district court decided the investors had lost over $4 million in equity, and resentenced Tom to 121 months.

Last Friday, it was the 10th Circuit’s turn to throw up its hands. The Circuit said it had clearly told the district court what had to be done – called “the law of the case” – and the district court was not entitled to go off on a frolic by ginning up a new theory on “loss of equity.”

The problem was simply this. Before Tom committed any fraud at all, the apartment project was circling the drain. After the fraud ended, the receiver enticed investors to toss even more money on the burn pile. The issue, then, was how much of the total loss was because of the fraud instead of because of external factors. The Court complained that the government’s inability to figure out the value of the investors’ stake in the deal on the day before the fraud began didn’t excuse complying with the Court of Appeals had ordered.

The district judge had said that she would have given Tom 121 months even if her Guideline calculation was too high. She pounded Tom at sentencing, saying “You lied to your victims, you stole their funds, and you failed to manage the investment properties in the manner you promised.” She complained that she could not find Tom responsible for “the full $12 million he stole from investors”

The 10th Circuit was not impressed with the district court’s alternate sentence. The sentencing judge’s “finding was clearly erroneous,” the Circuit said, “for there is no evidence that Mr. Evans stole money from investors. To the contrary, Mr. Evans contributed approximately $4.5 million of his own money to keep the business afloat. Mr. Evans’s misrepresentations could conceivably represent a form of “stealing” if the misrepresentations had caused investors to lose money. But… the government has been unable to prove loss to investors caused by the fraud.”

The 10th Circuit was not impressed with the district court’s alternate sentence. The sentencing judge’s “finding was clearly erroneous,” the Circuit said, “for there is no evidence that Mr. Evans stole money from investors. To the contrary, Mr. Evans contributed approximately $4.5 million of his own money to keep the business afloat. Mr. Evans’s misrepresentations could conceivably represent a form of “stealing” if the misrepresentations had caused investors to lose money. But… the government has been unable to prove loss to investors caused by the fraud.”

The appellate panel sent the case back for resentencing, and ordered it be heard by another judge. While the 10th noted – as appeals courts always do in cases like this – that it was sure the judge was not personally biased, it nevertheless noted several reasons for assigning a different judge:

First, the district judge repeatedly stated that Mr. Evans deserved a sentence enhancement, saying that it was unfortunate that the loss computation was not higher…. The judge added that she believed Americans “do not take white collar crime seriously enough… Even after we rejected the original loss calculation, the district judge reiterated her belief that Mr. Evans had “stole[n]” approximately $12 million and expressed regret concerning the inability to order restitution in that amount… Thus, we could reasonably expect our disposition to cause difficulty on remand.

Because the government had its chance prove loss but failed to do so, the Court ordered that a new sentence would not include any enhancement for loss or number of victims.

Because the government had its chance prove loss but failed to do so, the Court ordered that a new sentence would not include any enhancement for loss or number of victims.

Tom probably knew good news was coming. After this case was argued last November, the Court of Appeals ordered his release on bail on December 12th. He’s served three years, considerably more than what his corrected Guidelines suggest. Interestingly, Judge Neil Gorsuch was on the panel that considered the briefs and heard the argument. He recused himself before the judgment, because of his nomination to the Supreme Court only four days before the opinion issued.

United States v. Evans, Case No. 15-1461 (10th Circuit, Feb. 3, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root