We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

BLACK SWANS AND HOPEMONGERS

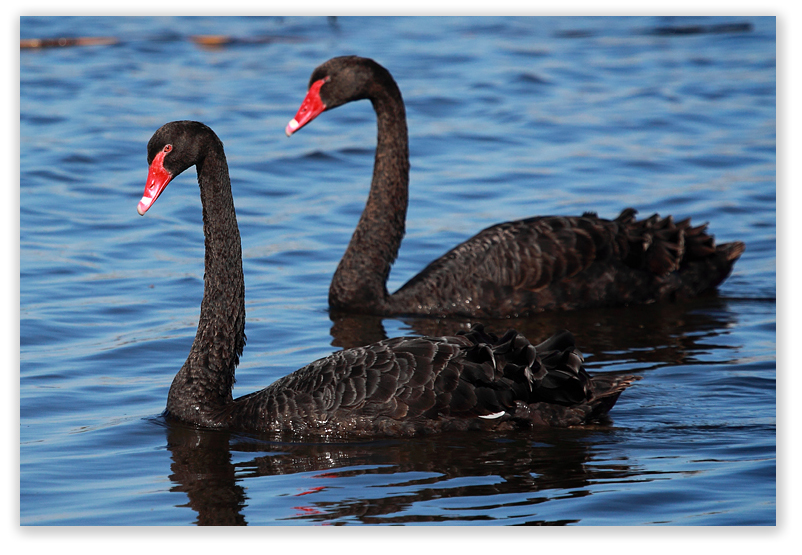

For many years before the 2010 psychological thriller movie, finance types knew that “Black Swan” was a metaphor describing an event that comes as a surprise, has a major effect, and is often inappropriately rationalized after the fact with the benefit of hindsight. The term was coined because a black swan was a creature that supposedly did not exist. Even after ornithologists found that such creatures do in fact exist, the term survived.

For many years before the 2010 psychological thriller movie, finance types knew that “Black Swan” was a metaphor describing an event that comes as a surprise, has a major effect, and is often inappropriately rationalized after the fact with the benefit of hindsight. The term was coined because a black swan was a creature that supposedly did not exist. Even after ornithologists found that such creatures do in fact exist, the term survived.

A far outlier of a district court decision is suddenly hot again, and for all the wrong reasons is being inappropriately rationalized with hindsight – or worse. We’ve had several inquiries about what inmates are calling “the Holloway Doctrine” in the last week. Compared to the two questions about Holloway we fielded in the last two and half years – the topic is suddenly “trending,” as they say in social media.

In July 2014, one of our favorite federal district court judges, the since-retired EDNY Judge John Gleeson, engineered the release of a mutt named Francois Holloway, who had been locked up back in the early 1990s for three carjackings. The problem with Frank’s crimes – besides the obvious that carjacking is illegal, dangerous and impolite to the driver – was that he liked brandishing a gun when he grabbed the cars. Thus, when Frank was indicted, the grand jury included three stacked 18 USC 924(c) counts.

Conviction on a 924(c) count carries a mandatory minimum of least 5 years, and those years must be consecutive to any other counts. What’s worse, a subsequent 924(c) conviction – even in the same case – carries a mandatory 25 years consecutive to any other count.

The government offered Frank a plea deal of about 11 years (by dropping two 924(c) counts), but in Frank’s worst decision since his idea to start carjacking, he turned it down and took them to trial. When the dust settled, Frank got a sentence of 57 years and change.

Frank filed a post-conviction motion under 18 USC 2255, but it was shot down in 2002. Twelve years later, he filed an F.R.Civ.P. 60(b) motion to reopen the 2255, rehashing the prior 2255 issues and arguing that a couple of new, non-retroactive Supreme Court cases should change the outcome.

In any other courtroom in America, a Rule 60(b) filed a decade after the underlying 2255 had been denied would have gone straight to the judicial shredder. But Judge Gleeson had always been troubled by the 57-year sentence the law required him to impose on Frank. In 2008, he had asked the EDNY U.S. Attorney to cut Frank a break. The U.S. Attorney refused. When the new Rule 60(b) motion arrived on his desk, the Judge called the U.S. Attorney again.

This time, the U.S. Attorney was an Obama appointee, Loretta Lynch (who became Obama’s Attorney General in late 2014). When Gleeson asked for her agreement to his granting Frank’s Rule 60(b), she agreed.

Frank’s family packed Judge Gleeson’s courtroom, the Judge cut his sentence to 20 years (which he had already served), and Frank walked out the courthouse door to freedom. A Disney moment, to be sure.

Frank’s family packed Judge Gleeson’s courtroom, the Judge cut his sentence to 20 years (which he had already served), and Frank walked out the courthouse door to freedom. A Disney moment, to be sure.

But the case is truly a Black Swan: something completely unexpected, clearly a big and wonderful event for Frank, and a decision without any precedential value or relevance to any of the other 189,219 inmates in federal custody.

Gleeson certainly worked justice, but he did not follow the law. First, the district court had no authority to grant a Rule 60(b) motion to set aside the judgment in the 2255 proceeding. Such motions are almost always considered second-and-successive, meaning the district court doesn’t even have jurisdiction to hear the motion, let alone grant it. In fact, the word “jurisdiction” doesn’t even appear in Judge Gleeson’s 11-page decision.

Second, even if Judge Gleeson had jurisdiction to hear the 10-year-too-late Rule 60(b) motion, the pleading was absolutely meritless. Gleeson said as much in his order.

Third, even if there was merit to the Rule 60(b) motion, nothing in its arguments supported vacating two 924(c) counts but leaving everything else the way it was.

But Gleeson was a wise judge, and he also knew that a district court can order anything it wants to order if the parties are all on board. Unless a party to case files a timely notice of appeal to challenge a decision, the order becomes final. Gleeson could have ordered the Government to buy Holloway pizza a day for the rest of his life, and – once the order was no longer appealable – Trump would still be delivering Domino’s to Holloway right now.

After Holloway, Anthony Luis Rivera got his “old law” sentence of 60 years cut in half by an Oklahoma court. The record is pretty thin on this decision, except we believe his lawyer’s colorful but featherweight motion was the origin of the term “Holloway Doctrine” to explain Gleeson’s “one-off” sentence cut for Frank Holloway.

What we do know about Rivera is that he had two “big law” firms, one a national firm that represents some of the largest corporations in the world, shilling for him pro bono. That was extraordinary, suggesting a fascinating back story which we don’t know. Tony’s “stream of consciousness” motion to vacate his life-without-parole sentence for cocaine distribution – imposed on him in the pre-Guidelines days of 1985 – was as long on background on the inmate as it was short on legal argument. Notably, the motion asked the district court to follow the Holloway Doctrine, which it argued “recognizes that district courts have the discretion, inherent in our American system of justice, to subsequently reduce a defendant’s sentence in the interests of fairness — even after all appeals and collateral attacks have been exhausted and there is neither a claim of innocence nor any defect in the conviction or sentence — when it has clearly been demonstrated that the original sentence sought by the United States and imposed by the court (even when mandated by law) is revealed to be disproportionately severe.”

What we do know about Rivera is that he had two “big law” firms, one a national firm that represents some of the largest corporations in the world, shilling for him pro bono. That was extraordinary, suggesting a fascinating back story which we don’t know. Tony’s “stream of consciousness” motion to vacate his life-without-parole sentence for cocaine distribution – imposed on him in the pre-Guidelines days of 1985 – was as long on background on the inmate as it was short on legal argument. Notably, the motion asked the district court to follow the Holloway Doctrine, which it argued “recognizes that district courts have the discretion, inherent in our American system of justice, to subsequently reduce a defendant’s sentence in the interests of fairness — even after all appeals and collateral attacks have been exhausted and there is neither a claim of innocence nor any defect in the conviction or sentence — when it has clearly been demonstrated that the original sentence sought by the United States and imposed by the court (even when mandated by law) is revealed to be disproportionately severe.”

This is palpable nonsense. Gleeson did not so hold, but rather used the vehicle of a pending Rule 60(b) to pull off a legal sleight-of-hand with the help of a pliable United States Attorney. In Tony Rivera’s case, besides the obvious fact that he was serving an “old law” sentence having nothing to do with the mandatory Sentencing Guidelines, the judge’s order vacating one of the two consecutive 30-year sentences mentions nothing about Holloway.

The final problem with Rivera is one anything who thinks the Holloway Doctrine is a watershed legal case should remember. Supreme Court decisions bind all lower courts. Decisions of the circuit courts of appeal bind all of the district courts in their respective circuits, just not other circuit courts and not district courts located elsewhere. But District court decisions – such as Holloway and Rivera – bind absolutely no one except the parties in the particular action.

Judge Gleeson did not create a Holloway Doctrine for the simple reason that he could not.

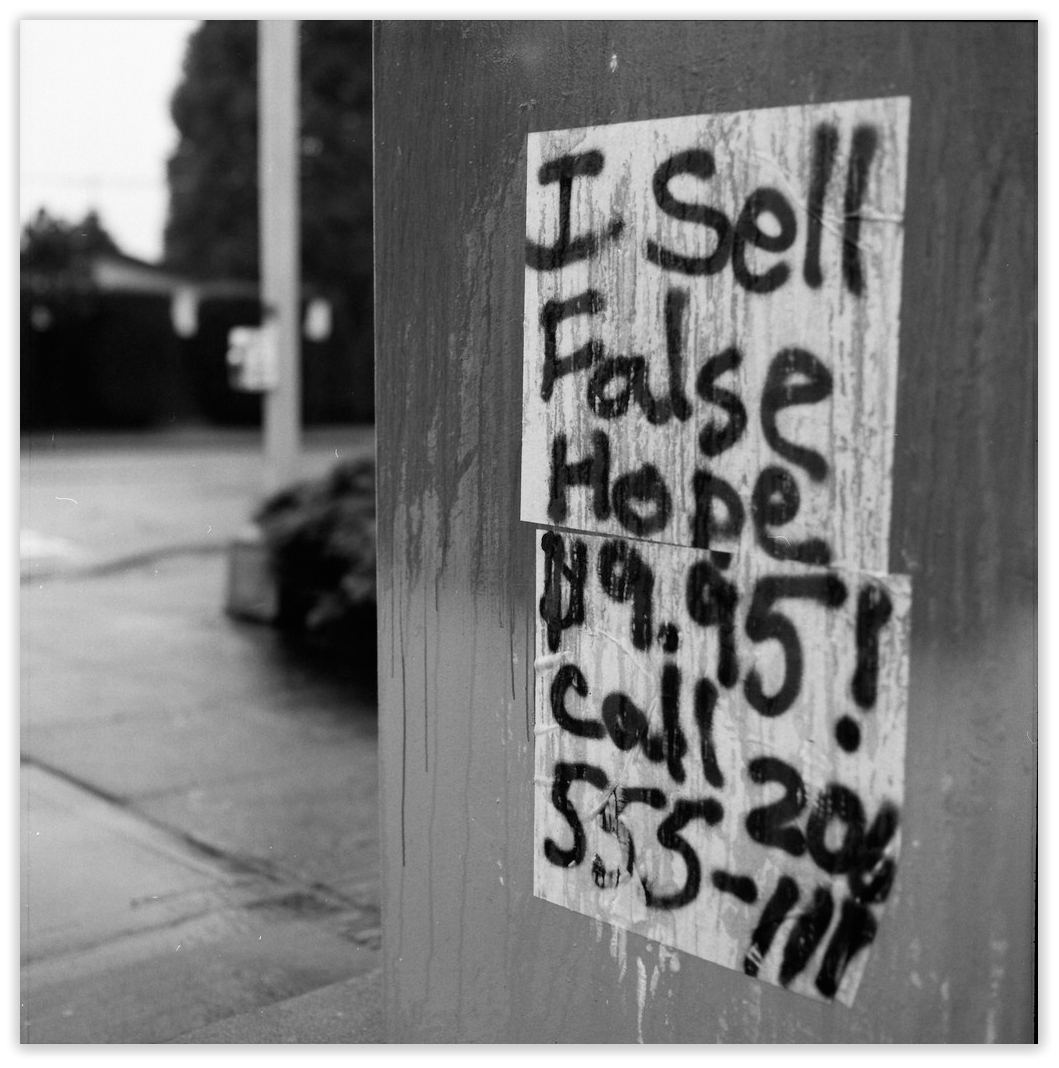

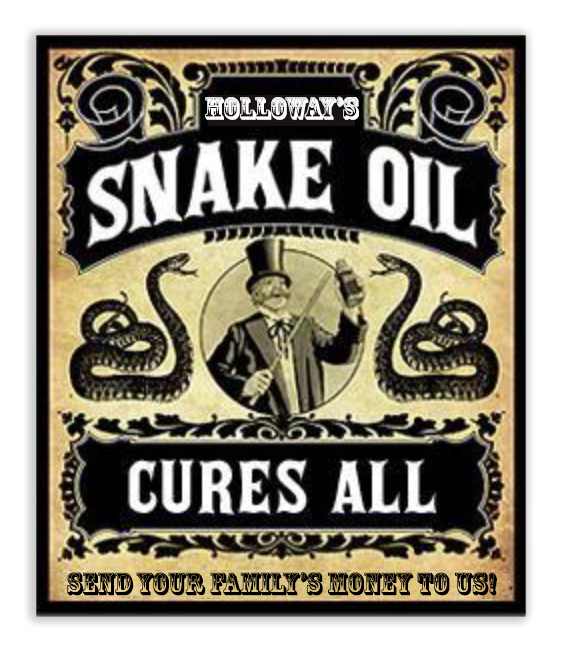

None of this has stopped some people in the “hope-monger” industry from soliciting inmates. They sell false hopes like snake oil, strapping inmates (and too often, their families) to pay for motions that are more fit to line parakeet cages than they are to land on judges’ desks.

None of this has stopped some people in the “hope-monger” industry from soliciting inmates. They sell false hopes like snake oil, strapping inmates (and too often, their families) to pay for motions that are more fit to line parakeet cages than they are to land on judges’ desks.

One email an inmate brought to our attention – from a “paralegal” firm, whatever that may be – trumpets that

if you were planning on filing a Clemency Petition you might still do so, but a more effective way of filing for early release may be the Holloway Doctrine. Request your free look to find out.

More effective way than what? Sending the Judge candy for Valentine’s Day? Baking a file into a cake?

The plain truth is that all an inmate needs to do get a break like Frank Holloway, is to (1) start out with stacked mandatory minimum sentences that a judge was forced to impose; (2) have a sentencing judge like John Gleeson, who complained at the sentencing that what he or she was imposing was too harsh; (3) find a U.S. Attorney like Loretta Lynch (rather than one likely to be appointed by President Trump) who will roll over and play dead at the judge’s request; (4) have a prison record of about 20 years of programming and good discipline; and (5) already have a pleading on file with the court that would give the court a colorable basis for granting relief. It would also help to be a minority: Judge Gleeson noted in the Holloway decision that “Black defendants like Holloway have been disproportionately subjected to the’ stacking’ of Sec. 924(c) counts that occurred here,” a fact that surely influenced his decision to convince the U.S. Attorney to agree to a rump reduction of sentence.

The plain truth is that all an inmate needs to do get a break like Frank Holloway, is to (1) start out with stacked mandatory minimum sentences that a judge was forced to impose; (2) have a sentencing judge like John Gleeson, who complained at the sentencing that what he or she was imposing was too harsh; (3) find a U.S. Attorney like Loretta Lynch (rather than one likely to be appointed by President Trump) who will roll over and play dead at the judge’s request; (4) have a prison record of about 20 years of programming and good discipline; and (5) already have a pleading on file with the court that would give the court a colorable basis for granting relief. It would also help to be a minority: Judge Gleeson noted in the Holloway decision that “Black defendants like Holloway have been disproportionately subjected to the’ stacking’ of Sec. 924(c) counts that occurred here,” a fact that surely influenced his decision to convince the U.S. Attorney to agree to a rump reduction of sentence.

We confess to being intolerant of people who peddle false hope to inmates as a means of picking their pockets. The folks shilling “the Holloway Doctrine” now are only a notch up from the “territorial jurisdiction” and “sovereign citizen” types. Holloway worked in Judge Gleeson’s courtroom. The Rivera decision worked once in Oklahoma, but is both a hot mess and utterly irrelevant to Guidelines sentences.

Inmates are more likely to see the Trump helicopter arrive at the prison to fly them home than to ever see these Black Swans swim by again.

Inmates are more likely to see the Trump helicopter arrive at the prison to fly them home than to ever see these Black Swans swim by again.

United States v. Holloway, 68 F.Supp.3d 310 (E.D.N.Y. 2014)

United States v. Rivera, Case No. 83-0096-CR (E.D.Okla. Sept. 15, 2015)

– Thomas L. Root