We’re still doing a weekly newsletter… we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way…

ECONOMIC CRIME SENTENCES ARE A SNAP

There’s a certain amount of irony in the Sentencing Guidelines’ approach to calculating fraud sentences. The process is akin to buying a car. You find a base price you can live with, but then you find that the options – such as sunroof, alloy wheels, sound system, steering wheel – all add dramatically to the price. Before you get out the door, you’ve also paid for extended warranties, dent and ding protection, and a few hundred bucks for document prep (whatever that is). And just like that, your sharp-eyed deal has morphed into the national debt.

The fraud guidelines in USSG Sec. 2B1.1 are like that. The base offense level for fraud is 6, which itself would yield a sentence of as low as probation. But before the defendant gets out the courthouse door, the amount of actual or intended loss may have more than doubled that number, and a gallimaufry of enhancements buried in the fine print – over 20 of them at last count – have added to it. It isn’t hyperbolic at all to suggest that the defendants would have been better off (sentencing-wise, at least) simply robbing their victims with a mask and a gun.

In a curious decision last week, the 2nd Circuit implied what many commentators have already argued, that the perverse and overblown sentencing effect of the 2B1.1 enhancements on a defendant’s base offense level — a sentencing construct for fraud “unknown to other sentencing systems” — virtually dictates that a district court impose a non-Guidelines sentence.

Ahmed Algahaim owned a suburban New York convenience store. Like many stores in this day and age of ubiquitous food stamps (now called SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), he accepted the three most widely-used pieces of plastic: Mastercard, Visa and EBT cards.

But unlike many stores, Ahmed would swap the swipe of a SNAP EBT card for cash (at a substantial discount, of course). His customers liked this, of course. Why buy cereal, oranges and milk when you can get 70 cents on the SNAP dollar to use to buy cigarettes and beer?

But unlike many stores, Ahmed would swap the swipe of a SNAP EBT card for cash (at a substantial discount, of course). His customers liked this, of course. Why buy cereal, oranges and milk when you can get 70 cents on the SNAP dollar to use to buy cigarettes and beer?

But while his patrons thought Ahmed’s scheme put the “convenient” in convenience store, the government took a dim view of the practice. Ahmed was convicted of food stamp fraud.

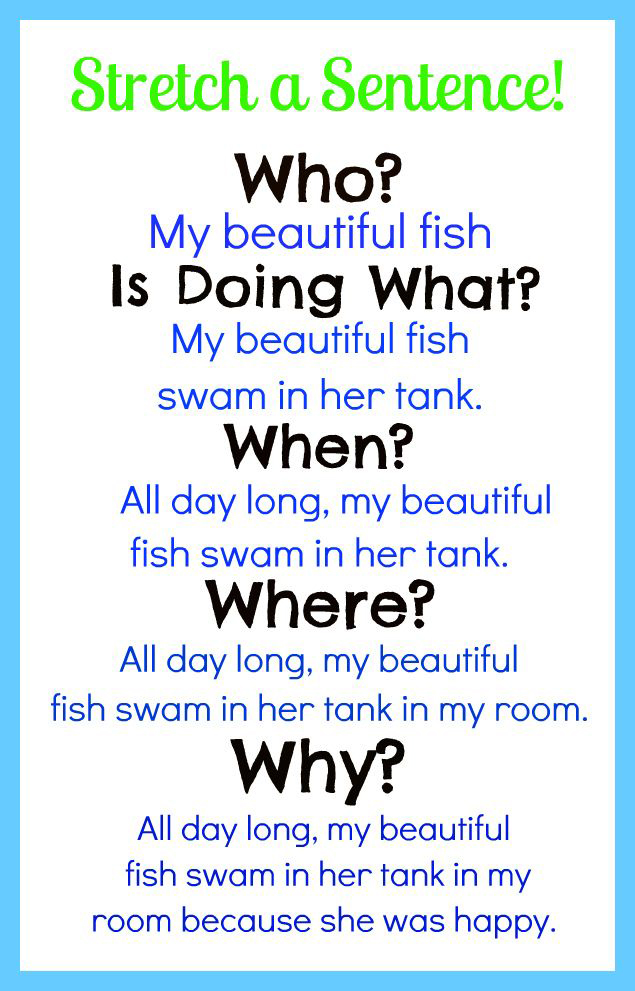

Most of the appeal was pretty plain vanilla, but a section of the decision considering Ahmed’s sentencing range was fascinating. His Guidelines calculation began with a base of 6. From 2B1.1’s loss table, 16 levels were added because of the amount of loss, for an adjusted offense level of 22 — three times the base level. With no prior criminal record, he got 21 months’ in prison. No one argued that his sentence was calculated correctly under the Guidelines.

To virtually everyone in the federal system, a guy with a 21-month sentence is considered a short-timer the day he arrives at the door. Nevertheless, the Court of Appeals remanded the case for resentencing.

2nd Circuit Judge Jon Newman acknowledged that it was within the Sentencing Commission’s authority to construct a sentencing scheme that “uses loss amount as the predominant determination of the adjusted offense level for monetary offenses.” Nevertheless, he observed that the Commission could (and should) have approached the problem differently:

For example, it could have started the Guidelines calculation for fraud offenses by selecting a base level that realistically reflected the seriousness of a typical fraud offense and then permitted adjustments up or down to reflect especially large or small amounts of loss. Instead the Commission valued fraud (and theft and embezzlement) at level six, which translates in criminal history category I to a sentence as low as probation, and then let the amount of loss, finely calibrated into sixteen categories, become the principal determinant of the adjusted offense level and hence the corresponding sentencing range. This approach, unknown to other sentencing systems, was one the Commission was entitled to take, but its unusualness is a circumstance that a sentencing court is entitled to consider.

The Court surprisingly concluded that “where the Commission has assigned a rather low base offense level to a crime and then increased it significantly by a loss enhancement, that combination of circumstances entitles a sentencing judge to consider a non-Guidelines sentence.” The Circuit didn’t say the sentence was erroneous in any way or even that the district court was unaware of its power to impose an alternative sentence. Rather, the 2nd just said in so many words that the cumulative effect of overlapping enhancements leads to nonsensical sentences, and that district courts should be sensitive to that.

Two 2nd Circuit criminal defense lawyers observed that “many judges have stated that the Guidelines are not helpful in white-collar cases and that their emphasis on loss can lead to results that are “patently unreasonable.” Practitioners have also advocated for shorter sentences in cases involving relatively low loss amounts or where the defendant had no prior record. See ABA Criminal Justice Section, A Report on Behalf of the ABA Criminal Justice Section Task Force on the Reform of Federal Sentencing for Economic Crimes (November 10, 2014). To the extent that district judges needed any further encouragement, Judge Newman’s decision lets district judges know that a Guidelines sentence need not be imposed where the “significant effect of the loss enhancement leads to an unduly long sentence.”

United States v. Algahaim, Case Nos. 15-2024(L), 15-2069(Con) (2nd Cir., Dec. 1, 2016)

Stephanie Teplin and Harry Sandick, Food For Thought: Court of Appeals Questions Relevance Of Guidelines To Case Of Fraud Involving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Dec. 2, 2016)