We’re still doing a weekly newsletter… we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way…

SANDBAGGED?

Pete Apicelli was being tried for running a marijuana grow operation in Campton, New Hampshire. He had been indicted after a town employee reported finding pot growing in a field, and the police set up a motion camera to catch the gardener responsible for it.

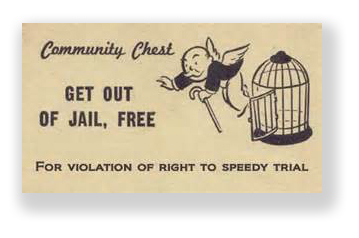

At trial, Pete complained that his Speedy Trial Act rights were violated, because more than 70 days elapsed between his indictment and trial. To a layman, this would seem to make sense, because his trial didn’t occur until something like a year and half after he was charged by the grand jury. But the name of the law codified at 18 U.S.C. 3161 – the Speedy Trial Act – is one rich in irony.

Officially, the STA requires that a defendant be tried within 70 days of the later of the indictment or initial appearance. If he or she is not, the penalty provisions of the STA mandate that “the information or indictment shall be dismissed on motion of the defendant.” But the 70 days are only “nonexcludable” days, which a wag once observed is any day of the week ending in “y.” At times, this does not seem to far from the truth.

Officially, the STA requires that a defendant be tried within 70 days of the later of the indictment or initial appearance. If he or she is not, the penalty provisions of the STA mandate that “the information or indictment shall be dismissed on motion of the defendant.” But the 70 days are only “nonexcludable” days, which a wag once observed is any day of the week ending in “y.” At times, this does not seem to far from the truth.

In calculating the 70-day period, a number of delays are excluded by the statute, including delays caused by continuances when the district court judge determines that “the ends of justice served by taking such action outweigh the best interest of the public and the defendant in a speedy trial.”

In Pete’s case, everyone agreed that 46 nonexcludable days passed between his initial appearance and the date on which he first filed a motion to continue the trial date. But then, Pete filed some motions, which normally begin “excludable time” under the STA.

Pete and the government disagreed on whether the STA clock continued to stand still during two periods in which the district court granted ends-of-justice continuances at Pete’s request. The district court said both delays served the ends of justice, and didn’t count them against the STA calendar. If they had counted, Pete’s STA rights would have been violated.

Normally, you’d think that filing something to stop the clock and then complaining that you were prejudiced because the STA clock stopped seems like shooting your parents and then complaining you deserve mercy for being an orphan. But Pete’s argument was a bit more nuanced than that. He argued the time his motions were pending should not be excluded from the STA, because the government had denied him the automatic discovery he was entitled to, and he had to file the motions in order to get it. Previously, the 1st Circuit had observed that “a defendant denied automatic discovery . . . would be placed snugly between a rock and a hard place: he could either forgo discovery to which he was entitled or he could file a motion to obtain it, thus stopping the speedy trial clock and easing the pressure on the government to bring him to trial.”

But last week, the 1st Circuit turned Pete down, refusing to hold that the government had sandbagged him. The appellate panel held that Pete did not allege that the government acted intentionally or delayed its discovery production to gain an unfair advantage. “Rather, he simply lists evidence he believes the Government should have disclosed at an earlier date and asks us to infer bad faith or government inattention from the delays themselves.” The Court held that Pete “neither explains why this evidence should have been part of the Government’s automatic discovery obligations nor does he appeal the district court’s finding that the Government was in compliance. We have long held that issues adverted to in a perfunctory manner, unaccompanied by some effort at developed argumentation, are deemed waived. Without any reason to doubt the district court’s findings that the Government had complied with its discovery obligations, we cannot find an STA violation from the delays themselves.”

What is interesting is what the Court did not say. It did not say that the government could stop the STA clock by forcing the defendant to move for the release of evidence that should have been automatically disclosed. It did not say that a defendant who was compelled to seek court assistance to obtain needed evidence had to choose between STA rights and trial preparation. In fact, the court’s holding that Pete failed to show a government discovery violation seemed to suggest that if he had been able to do so, his argument that he could move for court assistance without stopping the STA clock would have had merit.

United States v. Apicelli, Case No. 15-2400 (1st Circuit, Oct. 7, 2016)