We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just posting pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

KILLING FLIES WITH ELEPHANT GUNS

Do ex-offenders who complete their sentences deserve a clean slate? And how should that be balanced against the public’s right to safety, especially for children?

Currently, the federal and state correctional systems supervise about 6.9 million people. The FBI adds over 10,000 people a day to its database. About one-third of adults have been arrested by age 23. Together, local, state and federal law enforcement agencies are approaching 250 million arrests, resulting in close to 80 million individuals in the FBI criminal database. See Nicholas M. Wooldridge, A Federal Expungement Law Should Be a Priority in Any Future Criminal Justice Reform Effort, JURIST – Hotline (Sept. 22, 2016).

Some collateral consequences are nonsensical. Why should ex-offenders be stripped of the right to vote? Some are overbroad. Those convicted of violent offenses probably should be denied firearms, but why should someone with a 30-year old check forgery conviction be denied the right to shoot skeet?

Now add to the mix two explosive factors, the first being protection of our children and the second being that the ex-offenders were convicted of child sex offenses. Most people would say that too much is not enough. The 11th Circuit grappled with that question last week, looking at what is touted as the strictest sex offender residency law in America.

Now add to the mix two explosive factors, the first being protection of our children and the second being that the ex-offenders were convicted of child sex offenses. Most people would say that too much is not enough. The 11th Circuit grappled with that question last week, looking at what is touted as the strictest sex offender residency law in America.

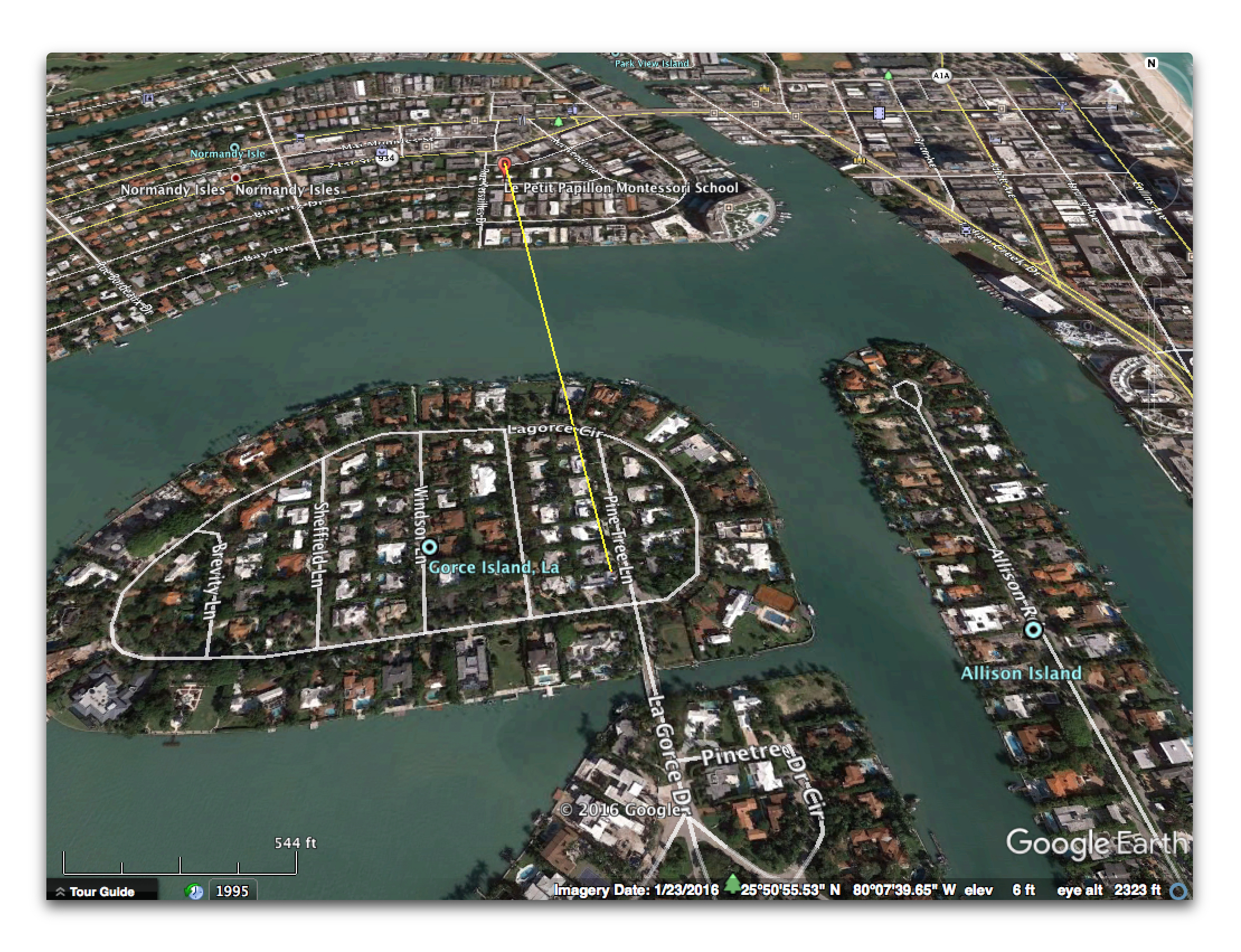

Miami-Dade County adopted an ordinance in 2005 that prohibits a person convicted of any one of several enumerated sexual offenses involving a victim under 16 years old from residing “within 2,500 feet of any school.” The 2,500-foot distance is “measured in a straight line from the outer boundary of the real property that comprises a sexual offender’s or sexual predator’s residence to the nearest boundary line of the real property that comprises a school,” rather than “by a pedestrian route or automobile route.” The plaintiffs – people who had been convicted of such offenses – sued, claiming that the collateral consequence was an ex post facto punishment prohibited by the Constitution.

The district court threw out the case, but the 11th Circuit reinstated the case for several of the plaintiffs who proved they had been convicted before the ordinance was enacted.

An ex post facto law is a law that applies to events occurring before its enactment and that disadvantages the offender affected by it, by altering the definition of criminal conduct or increasing the punishment for the crime. If the law imposes collateral consequences on offenders, the Supreme Court has adopted a two-stage inquiry. If the intention is to impose punishment, the ordinance is a prohibited ex post facto law. If the act’s intention was to enact a regulatory scheme that is civil and nonpunitive, the court looks at whether the effect is nevertheless so punitive either in purpose or effect “as to negate the State’s intention to deem it civil.”

Here, the County argued its ordinance was intended to be civil and nonpunitive. Accepting that, the Court focused on the effect it had on people who were subject to it and were convicted before its passage. One of the plaintiffs alleged he “was twice instructed by probation officers to live at homeless encampments after the County’s residency restriction made him unable to live with his sister and he could not find other housing compliant with the restriction. He currently lives at a makeshift homeless encampment near ‘an active railroad track’.” Another plaintiff said he “sleeps in his car at the encampment because, ‘despite repeated attempts, he has been unable to obtain available, affordable rental housing in compliance with the Ordinance’.”

The Court found the plaintiffs also had adequately alleged the ordinance went well beyond what was necessary to protect the public. They claimed “an individual becomes subject to the restriction based solely on the fact of his or her prior conviction for a listed sexual offense, without regard to his or her individual ‘risk of recidivism over time’… despite the fact that ‘research has consistently shown that sexual offender recidivism rates are among the lowest for any category of offenses, and that this lower risk of sexual offense recidivism steadily declines over time’. Nonetheless, the County’s residency restriction applies for life, even after an individual no longer has to register as a sexual offender under Florida law and is no longer subject to the state law 1,000-foot residency restriction. The County’s residency restriction also applies ‘even if there is no viable route to reach the school within 2500 feet’.”

Finally, plaintiffs argued that by forcing them into homelessness, the ordinance made it that much harder for them to obtain treatment, which is the only proven means of reducing recidivism.

The Court’s role at this point in the proceeding was only to determine whether the plaintiffs had stated a plausible claim, such that they should be permitted to proceed. The appellate panel ruled that Doe #1 and Doe #3 “alleged sufficient facts to raise plausible claims that the County’s residency restriction is so punitive in effect that it violates the ex post facto clauses of the federal and Florida Constitutions. Whether Doe #1 and Doe #3 ultimately prevail is a determination for a future stage of this litigation.”

Doe v. Miami-Dade County, Case No. 15-14336 (11th Cir., Sept. 23, 2016)