We’re still doing a weekly newsletter … we’re just starting to post pieces of it every day. The news is fresher this way …

LIVE THE LIFE

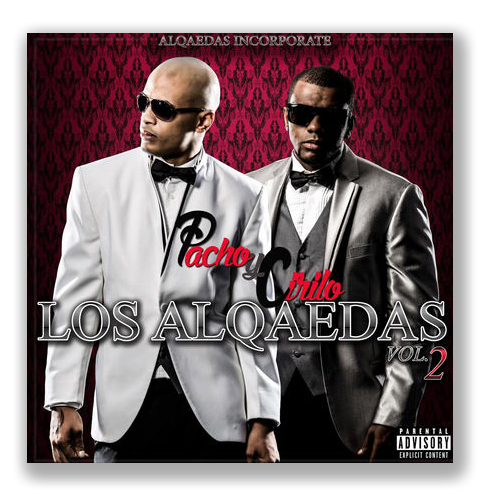

Neftalí Alvarez-Núñez, better known in the music world as “Pacho,” portrayed the gangsta life as it’s lived in San Juan and Miami. As Pacho y Cirilo, he and his partner were a YouTube with hits like “Mi Gatita Es Calle” and “La Emenencia Un Beso.” (It’s pretty good stuff, available on iTunes and through Amazon, too).

But life started imitating art, and Neftalí was caught discarding a gun as he left a San Juan nightclub. And not just any gun. This one was apparently the same piece that starred in “Mi Gatita Es Calle,” a Glock with an extended magazine that had been tweaked to fire in full-auto mode.

Neftalí had no criminal history, but he was addicted to Percocet, and so the obliging United States Attorney charged him as a drug-abuser-in-possession of a firearm (a subparagraph under 18 U.S.C. § 922, much less known that its big brother, felon-in-possession) and possession of a machingun. Neftalí’s Guideline sentencing range was only 24-30 months.

The Presentence Report, however, veered into music criticism, and the Probation Officer was no music lover. The PSR proposed an above-Guideline sentence because Pacho y Cirilo’s songs “promote violence, drugs and the use of weapons and violence, as . . . can be seen through their videos which are readily available on the internet.” The Report included translations of two songs performed by Pacho y Cirilo. “Dicen Que Vienen Por Mi” and “Como Grita El Palo.”

The Judge was not much for that genre, either. Deciding that the lyrics reflected Neftalí’s disdain for the law, love of guns and glorification of the drug culture, the District Court gave Neftalí 96 months, more than three times the top end of his Guidelines.

Last Friday, the 1st Circuit reversed the sentence. While it is true, the Court said, “that the Constitution does not erect a per se barrier to the admission of evidence concerning one’s beliefs and associations at sentencing simply because those beliefs and associations are protected by the First Amendment,” at the same time, “a defendant’s abstract beliefs, however obnoxious to most people, may not be taken into consideration by a sentencing judge.” Conduct protected by the First Amendment may be considered in imposing sentence only to the extent that it is relevant to the issues in a sentencing proceeding.

The Government argued that Pacho’s rather graphic lyrics reflected his beliefs, and thus was relevant to the sentencing issues. The District Court agreed, arguing that Neftalí’ “is an individual who makes a life . . . not only carrying this kind of firearm, but also preaching . . . the benefits of having this kind of firearm, the use you can give to them, expressing how you kill people, expressing how you don’t care about human life.”

The 1st Circuit rejected the District Court’s analysis. The appeals panel said that “implicit in this rationale is the assumption that the lyrics and music videos accurately reflect the defendant’s motive, state of mind, personal characteristics, and the like. But this assumption ignores the fact that much artistic expression, by its very nature, has an ambiguous relationship to the performer’s personal views. That an actress plays Lady Macbeth, or a folk singer croons “Down in the Willow Garden,” or an artist paints “Judith Beheading Holofernes,” does not, without more, provide any objective evidence of the performer’s motive for committing a crime, of his personal characteristics (beyond his ability to act, sing, or paint, as the case may be), or of any other sentencing factor.”

The Court of Appeals said, “In the absence of such extrinsic evidence, the mere fact that a defendant’s crime happens to resemble some feature of his prior artistic expression cannot, by itself, establish the relevance of that expression to sentencing.”

The case was sent back for resentencing.

United States v. Alvarez-Núñez, Case No. 15-2127 (1st Cir. July 8, 2016)