This week:

9th Circuit Gives New Hope for Sentence Reduction Grants to Rule 11(c)(1) Defendants

The Sobering Math on Clemency

DOJ Finds That BOP is Overcharged for Outside Medical Care

Get Your Facts Straight – Then You Can Hammer the Defendant

BOP “Revolving Door” Blamed for Poor Oversight of Private Prisons

On the 30th Anniversary of Len Bias’ Death, Time Conspires Against Sentencing Reform

9th CIRCUIT GIVES NEW HOPE FOR SENTENCE REDUCTION GRANTS TO RULE 11(c)(1) DEFENDANTS

The Sentencing Commission reports that, year to year, about 97 percent of all federal defendants take plea deals. One of the options for a plea deal – Rule 11(c)(1) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure – lets the government and defendant agree on a specific sentence. The judge then can either accept the sentence as agreed upon, or reject the sentence, in which case the plea agreement dies and the defendant reverts to a “not guilty” plea.

The Sentencing Commission reports that, year to year, about 97 percent of all federal defendants take plea deals. One of the options for a plea deal – Rule 11(c)(1) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure – lets the government and defendant agree on a specific sentence. The judge then can either accept the sentence as agreed upon, or reject the sentence, in which case the plea agreement dies and the defendant reverts to a “not guilty” plea.

A Rule 11(c)(1) plea is often a pretty good deal, because the defendant knows just what’s coming down the road. But over the past few years, a lot of defendants have had buyer’s remorse, after they found out that the 2-level reductions in the drug tables didn’t necessarily help them.

The issue got to the Supreme Court a few years ago in Freeman v. United States. The opinion was badly fractured, with the consensus generally being interpreted to be that an 11(c)(1) defendant could only get a 2-level reduction if the plea agreement showed that his or her agreed-on sentence was set in reliance on the Guidelines.

Last week, the en banc 9th Circuit took a fresh whack at interpreting Freeman, and reversed a district court’s determination that Tyrone Davis was not eligible for the 2-level reduction. Applying Marks v. United States, a Supreme Court case that explains how to interpret fractured Supreme Court opinions, 9th held that Freeman lacks a controlling opinion “because the plurality and concurring opinions do not share common reasoning whereby one analysis is a logical subset of the other.”

This sounds pretty dry so far, but what it means, the Court said, is “even when a defendant enters into an 11(c)(1)(C) agreement, the judge’s decision to accept the plea and impose the recommended sentence is likely to be based on the Guidelines; and when it is, the defendant should be eligible to seek § 3582(c)(2) relief.” The Court thus ruled that all Freeman says is that “defendants sentenced under Rule 11(c)(1)(C) agreements are not categorically barred from seeking a sentence reduction under § 3582(c)(2).”

Most other circuits have read Freeman restrictively, with only the D.C. Circuit joining the interpretation adopted last week by the 9th. This could set up a Supreme Court revisiting of the issue, as defendants elsewhere file for 2-level § 3582(c)(2) reductions, only to be denied by courts of appeal that disagree with the 9th and D.C. Circuits.

The 9th Circuit argues that by the 2-level reductions “Congress and the Sentencing Commission sought to address the urgent and compelling problem of crack-cocaine sentences. To read Freeman as restrictively as other courts have done extends the benefit of the Commission’s judgment only to an arbitrary subset of defendants whose agreed sentences were accepted in light of a since-rejected Guidelines range based on whether their plea agreements refer to the Guidelines.”

United States v. Davis, Case No. 13-30133 (9th Cir. June 13, 2016)

THE SOBERING MATH ON CLEMENCY

For anyone wondering about the snails’ pace of the disorganized Obama clemency process – which a Reason article last week said has “stranded many of the prisoners and families it was supposed to help” – a remedial math lesson is all that’s required.

For anyone wondering about the snails’ pace of the disorganized Obama clemency process – which a Reason article last week said has “stranded many of the prisoners and families it was supposed to help” – a remedial math lesson is all that’s required.

In January 2016, Pardon Attorney Deborah Leff quit barely a year after she got the job. Leff complained that DOJ had “not fulfilled its commitment to provide the resources necessary for my office to make timely and thoughtful recommendations on clemency to the president.” According to USA Today, “Leff said Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates had overruled her recommendations in an increasing number of cases—and that in those cases, the president was unaware of the difference of opinion.” After her departure, a longtime federal prosecutor, Robert A. Zauzmer, was appointed to fill her shoes.

Since Leff’s departure, the Office of the Pardon Attorney remains overwhelmed. In January, the office only had 10 lawyers, which The New York Times noted is “virtually the same size it was 20 years ago,” despite the fact that the number of clemency petitions has increased substantially. “From all accounts of what we’ve heard, the president is personally engaged in this issue,” an observer said. “I think the problem isn’t lack of will, but the lack of infrastructure.”

Early this year, OPA announced it was hiring 16 new attorneys, which would bring the total number of lawyers in the office to 26.

With 10,621 commutation petitions pending in May, and only 26 attorneys available to review, this means that each staffer is responsible for thoroughly reviewing roughly 408 petitions each over the next 6 or so months before Obama leaves office. And the petitions lucky enough to get vetted through the first stage have to endure the bureaucratic vetting process in place before eventually landing on the president’s desk.

Volunteer lawyers known as Clemency Project 2014 have been vetting petitions for the Pardon Attorney. As of June 2, CP14 has sent only 1,150 petitions to the Office of the Pardon Attorney for review. Of those, 145 petitions have been acted on, which means they’ve either been granted or denied by the President, and 111 have been granted.

At this pace, the Reason article argued, “it seems likely that Obama’s clemency initiative will benefit few, while the majority of otherwise eligible inmates will remain behind bars.”

Reason, President Obama’s Clemency Project is a bureaucratic nightmare (June 10, 2016)

DOJ FINDS THAT BOP IS OVERCHARGED FOR OUTSIDE MEDICAL CARE

The Department of Justice Office of Inspector General complained in a report last week that BOP spent $100 million in 2014 than other federal agencies paid for the same services. Thus, the report suggested, it’s not surprising that BOP’s spending for outside medical services increased 24 percent that year, while its overall budget increased at less than half that rate.

The OIG said, “We found that the BOP is the only federal agency that pays for medical care that is not covered under a statute or regulation under which the government sets the agency’s reimbursement rates, usually at the Medicare rate. Instead, the BOP solicits and awards a comprehensive medical services contract for each BOP institution to obtain outside medical services. At the end of FY 2014, all of the BOP’s comprehensive medical services contracts paid a premium above the applicable rates paid by Medicare for medical services.”

The OIG said, “We found that the BOP is the only federal agency that pays for medical care that is not covered under a statute or regulation under which the government sets the agency’s reimbursement rates, usually at the Medicare rate. Instead, the BOP solicits and awards a comprehensive medical services contract for each BOP institution to obtain outside medical services. At the end of FY 2014, all of the BOP’s comprehensive medical services contracts paid a premium above the applicable rates paid by Medicare for medical services.”

The report said that BOP “has historically opposed” to being required to may Medicare reimbursement rates, like other federal law enforcement agencies are required to do. BOP said that because its inmates are generally incarcerated for longer periods than detainees held by other federal law enforcement agencies, it must provide both acute and chronic (long-term) medical care for its inmates, while other law enforcement agencies provide only acute care. The OIG found that BOP “has not fully explored other legislative options that might help it control its medical costs without compromising provider access… As a result, while federal law requires that medical providers who treat members of the military and their dependents, Veterans, Native Americans, federal pre-trial detainees, and immigration detainees accept the Medicare rate when reimbursed by the federal government, those same providers are allowed to charge the BOP a premium above the Medicare rate when treating BOP inmates.”

DOJ Office of Inspector General, The Federal Bureau of Prisons’ reimbursement rates for outside medical care (June 2016)

GET YOUR FACTS STRAIGHT… THEN HAMMER THE DEFENDANT

Defendant John Doe Brown (we’re using a pseudonym here) was convicted of production of child porn, for photographing three minors. The district court hammered him with a 60-year sentence, commenting repeatedly on “the trauma to these three children,” the fact that “three children” would have to “worry for the rest of their lives” about the photographs, and that Brown “destroyed the lives of three specific children.”

The problem was that while two of the kids had been posed for pictures, John Doe had taken photos of the third child only while she slept. In fact, her mother declined to submit a victim impact statement specifically because her daughter “was unaware of the abuse” and had experienced “no negative impact.”

Last week, the 2nd Circuit reversed the sentence, underscoring a problem that is generally applicable to all federal defendants. The appellate court explained that “the district court’s explanation suggests that the individual harm suffered by each of Brown’s three victims played a critical role in its decision to impose three consecutive 20‐year sentences. But the sentencing transcript also suggests that the district court may have misunderstood the nature of that harm as to Brown’s third victim. Three times the court emphasized the mental anguish that “three specific children” would suffer as a result of Brown’s abuse. Brown’s third victim, however, has no knowledge of having been victimized. To be sure, the district court was entitled to punish Brown for that abuse regardless of whether the victim was aware of it. But given the district court’s repeated emphasis on the fact that Brown had destroyed the lives of “three specific children,” we conclude that it is appropriate to remand for resentencing to ensure that the sentence is not based on a clearly erroneous understanding of the facts.”

The Court said “we understand and emphatically endorse the need to condemn Brown’s crimes in the strongest of terms. But the Supreme Court has recognized that ‘defendants who do not kill, intend to kill, or foresee that life will be taken are categorically less deserving of the most serious forms of punishment than are murderers’… The sentencing transcript suggests that the district court may have seen no moral difference between Brown and a defendant who murders or violently rapes children, stating that Brown’s crime was “as serious a crime as federal judges confront,” that Brown was “the worst kind of dangerous sex offender,” and that he was “exactly like” sex offenders who rape and torture children. Punishing Brown as harshly as a murderer arguably frustrates the goal of marginal deterrence, “that is, that the harshest sentences should be reserved for the most culpable behavior…” Finally, to the extent that the district court believed it necessary to incapacitate Brown for the rest of his life because of the danger he poses to the public, we note that defendants such as Brown are generally less likely to reoffend as they get older.”

The Court said “we understand and emphatically endorse the need to condemn Brown’s crimes in the strongest of terms. But the Supreme Court has recognized that ‘defendants who do not kill, intend to kill, or foresee that life will be taken are categorically less deserving of the most serious forms of punishment than are murderers’… The sentencing transcript suggests that the district court may have seen no moral difference between Brown and a defendant who murders or violently rapes children, stating that Brown’s crime was “as serious a crime as federal judges confront,” that Brown was “the worst kind of dangerous sex offender,” and that he was “exactly like” sex offenders who rape and torture children. Punishing Brown as harshly as a murderer arguably frustrates the goal of marginal deterrence, “that is, that the harshest sentences should be reserved for the most culpable behavior…” Finally, to the extent that the district court believed it necessary to incapacitate Brown for the rest of his life because of the danger he poses to the public, we note that defendants such as Brown are generally less likely to reoffend as they get older.”

One does not have to like crimes such as John Doe’s offense to understand – often from personal experience – that some district judges get hyperbolic at sentencing, and often mangle the facts. The 2nd Circuit decision suggests that appeals that focus on intemperate remarks at sentencing may be fruitful.

United States v. Brown, Case No. 13-1706 (2nd Cir. June 14, 2016)

BOP “REVOLVING DOOR” BLAMED FOR POOR OVERSIGHT OF PRIVATE PRISONS

Review of 20,000 pages of records obtained from the BOP after a Freedom of Information Act request has led to a scathing report in The Nation last week, that accuses the BOP of ignoring signals of terrible conditions in private prisons with which it contracts.

A fatal 2012 uprising at Adams County Correctional Center in Natchez, Mississippi – run by Corrections Corporation of America – was one of four riots to explode in the BOP’s private prisons since 2008, all triggered by grievances over medical care. The trove of previously unreleased monitoring reports, internal investigations, and other documents show that the BOP had been warned of substandard care by its own monitors for years but failed to act.

Doug Martz, chief of the BOP’s private-prison contracting office at the time of the riot, said, “Even before the officer was killed, there were significant issues” with CCA’s management. “Inadequate medical care, low staffing levels, food-service issues. When you put all those together, it became ignitable.” After the riot, he says, “We wanted to walk away.” But when he sent a closure recommendation up the chain to the bureau’s CFO, Martz says, “We were flat out told, ‘No.’ ”

Martz, who retired in in 2014 after 25 years with the BOP, says that the agency’s failure to shut down Adams was due in part to a cozy relationship between bureau leadership and private-prison operators. In 2011, for example, just a year before the riot, BOP director Harley Lappin – who resigned at the same time he was arrested for drunk driving – joined CCA as executive vice president. Last year, he earned more than $1.6 million. At least two other BOP directors have also moved on to leadership positions at companies with BOP contracts, and Martz charges that one of them appeared at bureau meetings with contractors. “It made things difficult,” he says.

Martz, who retired in in 2014 after 25 years with the BOP, says that the agency’s failure to shut down Adams was due in part to a cozy relationship between bureau leadership and private-prison operators. In 2011, for example, just a year before the riot, BOP director Harley Lappin – who resigned at the same time he was arrested for drunk driving – joined CCA as executive vice president. Last year, he earned more than $1.6 million. At least two other BOP directors have also moved on to leadership positions at companies with BOP contracts, and Martz charges that one of them appeared at bureau meetings with contractors. “It made things difficult,” he says.

Last February, The Nation reported that at least 38 men died in privately run BOP prisons from 1998 to 2014 due to inadequate medical care. The new records show that in the last 9 years alone, BOP monitors documented 34 inmate deaths due to substandard medical care. Fourteen of the deaths occurred in prisons run by CCA. Fifteen others were in prisons operated by the GEO Group.

The report says, “In some facilities, inmates went months without seeing a doctor. Some prisoners who required emergency care were not transferred to a hospital, in an apparent attempt to save costs.”

According to The Nation, “The records and interviews with former BOP officials reveal a pattern: Despite dire reports from dozens of field monitors, top bureau officials repeatedly failed to enforce the correction of dangerous deficiencies and routinely extended contracts for prisons that failed to provide adequate medical care.”

The Nation, Federal Officials Ignored Years of Internal Warnings About Deaths at Private Prisons (June 15, 2016)

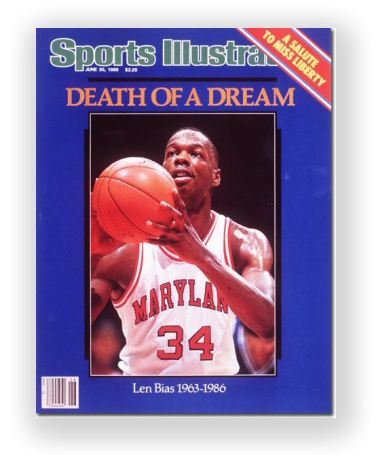

ON THE 30TH ANNIVERSARY OF LEN BIAS’ DEATH, TIME CONSPIRES AGAINST SENTENCING REFORM

In life, Len Bias was basketball’s next great hope, contender for a crown that went instead to Michael Jordan. In death, he became a trigger for the war on drugs.

In life, Len Bias was basketball’s next great hope, contender for a crown that went instead to Michael Jordan. In death, he became a trigger for the war on drugs.

NBC Sports reported last weekend that Bias’s 1986 cocaine overdose helped sparked a panic, stoked by false rumors about crack cocaine – which was not involved in Bias’s overdose and death – and a high-stakes bipartisan political furor against drugs. When the dust had settled, the Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1986 had been passed, the 100-to-1 ratio for crack to powder coke had been adopted, and thousands of low-level drug offenders — most of them young and black — were destined to become federal inmates over the next three decades.

Thirty years later, NBC says, America is still reeling from the impact. In the year before the ADA passed, there were about 35,000 people in federal prison, 9,500 of whom were in on drug charges. Today, according to the BOP, there are about 195,000 federal inmates, with half serving time for drugs.

So where is the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015? It’s pretty much stalled, with the Senate version (S. 2123) not scheduled for floor action, and the House version (H.R. 3713) still locked in a dispute between Democrats and Republicans over mens rea reform.

In the Senate, the raging battle is between conservatives who support reform and conservatives who oppose it. Last week, the conservative Federalist argued that the “Sentencing Act is not perfect. No legislation is. But it represents a good-faith, bipartisan effort to improve our prisons and courts, making the former more efficient and the latter more fair. It is broadly in line with state-level reforms that have already yielded considerable success. The proposed measures are also modest, making it exceedingly unlikely this law will precipitate a crime wave. It is a well-conceived and responsible piece of legislation.”

The conservative Heritage Foundation’s Daily Signal ran a puzzling piece last week which told the story non-violent drug offender Sherman Chester (who recently received a commutation after serving 20 years of his draconian mandatory minimum sentence) even while arguing that the 1986 ADA was a good idea at the time. But now, the Daily Signal says, “when it comes to reforming mandatory minimum laws, it is important to consider the nature of the serious offenses giving rise to such penalties and the harms they cause to society. At the same time, it is important to consider what should be done for people like Sherman Chester so that, in appropriate cases, the quality of mercy is not strained. This is a discussion worth having.”

Julie Stewart, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, wrote a piece in the liberal Huffington Post last week urging Congress to make the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive, but given the fact that S. 2123 has already had many of its retroactive provisions gutted in order to garner Republican support, the likelihood that Congress would ram through FSA retroactivity in the waning days of 2016 falls somewhere between slim and none.

In fact, the odds that the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 will be voted on before the end of the year are getting pretty long. The Senate only has 60 more work days this year, the House 46. A new Congress starts in January, meaning that any bill still pending at the end of the year will disappear, and the process must start over in 2017.

Legal Information Services Associates provides research and drafting services to lawyers and inmates. With over 20 years experience in post-conviction motions and sentence modification strategy, we provide services on everything from direct appeals to habeas corpus to sentence reduction motions to halfway house and home confinement placement. If we can help you, we’ll tell you that. If what you want to do is futile, we’ll tell you that, too.

If you have a question, contact us using our handy contact page. We don’t charge for initial consultation.